Rowan University Rowan University

Rowan Digital Works Rowan Digital Works

Theses and Dissertations

6-6-2018

Making college admission count: the importance of admission Making college admission count: the importance of admission

criteria in the current undergraduate admission process criteria in the current undergraduate admission process

Amanda Rachel Tessler

Rowan University

Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd

Part of the Higher Education Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Tessler, Amanda Rachel, "Making college admission count: the importance of admission criteria in the

current undergraduate admission process" (2018).

Theses and Dissertations

. 2574.

https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/2574

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion

in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. For more information, please

contact graduateresearch@rowan.edu.

!

!

MAKING COLLEGE ADMISSION COUNT: THE IMPORTANCE OF

ADMISSION CRITERIA IN THE CURRENT UNDERGRADUATE

ADMISSION PROCESS

by

Amanda Tessler

A Thesis

Submitted to the

Department of Educational Services and Leadership

College of Education

In partial fulfillment of the requirement

For the degree of

Master of Arts in Higher Education

at

Rowan University

May 1, 2018

Thesis Chair: Burton R. Sisco, Ed.D.

!

!

© 2018 Amanda Rachel Tessler

!

!

Dedication

I would like to dedicate this to my parents. Thank you both for always pushing me

to do better and supporting me, not only in graduate school, but my personal life as well.

Without you, I would have never found myself in graduate school with aspirations of

continuing my education and becoming the doctor in the family. Because of you, I am

always pushing myself harder, and wanting even more for myself. Thank you both.

iv

!

Acknowledgments

First, I would like to thank my family for supporting me throughout grad school.

Thank you for letting me miss holidays and being so understanding when you could not

see me for months at a time.

I would also like to thank my friends and coworkers for encouraging me,

understanding how busy I have been over the past two years, letting me vent, and

listening to me complain and stress over the work I needed to do. Now that this is

finished, I can finally have a social life with you all again!

Thank you to my boyfriend who has only known me as a graduate student and has

stuck around this whole time. Thank you for supporting me, letting me cancel plans, and

staying in at night and on weekends with me when I was too tired to do anything. I

definitely could not have done it without you.

Lastly, thank you to Dr. Sisco for his guidance and knowledge throughout these

past two years. With your support, I gained a deeper knowledge and stronger passion for

research.

v!

!

Abstract

Amanda Tessler

MAKING COLLEGE ADMISSION COUNT: THE IMPORTANCE OF ADMISSION

CRITERIA IN THE CURRENT UNDERGRADUATE ADMISSION PROCESS

2017-2018

Burton R. Sisco, Ed.D.

Master of Arts in Higher Education

During these changing times in higher education, admission criteria for being

accepted into a four-year institution for higher education continues to evolve. This study

discovered the attitudes that guidance counselors and admission officers, from public

schools throughout New Jersey, had about these criteria, and what they believed is most

important for current students applying to college. Two surveys were developed and

distributed via email to guidance counselors of public high schools throughout New

Jersey, as well as admission officers of public four-year institutions throughout New

Jersey. Results suggest that quantitative admission criteria, SAT and ACT scores and

HSGPA, are the most important, and also course load and transcript. Further research

should look to discover the reasoning behind why each of these are so important, as well

as looking to discover how important these admission criteria are to students currently

applying to college.

hi

vi!

!

Table of Contents

Abstract ............................................................................................................................v

List of Tables ...................................................................................................................ix

Chapter I: Introduction .....................................................................................................1

Statement of the Problem ...........................................................................................1

Purpose of the Study ..................................................................................................1

Significance of the Study ...........................................................................................2

Assumptions and Limitations ....................................................................................2

Operational Definitions ..............................................................................................3

Important Acronyms ..................................................................................................4

Research Questions ....................................................................................................4

Overview of the Study ...............................................................................................5

Chapter II: Review of the Literature ................................................................................6

Current Admissions Process and Requirements ........................................................6

Quantitative Admission Criteria ................................................................................9

Standardized Testing ............................................................................................9

High School GPA ................................................................................................14

Class Rank ...........................................................................................................14

Qualitative Admission Criteria ..................................................................................15

Extracurricular Activities .....................................................................................16

Personal Essays ....................................................................................................17

Letters of Recommendation .................................................................................18

Interviews .............................................................................................................19

vii!

!

Table of Contents (Continued)

District Factor Grouping (DFG) ..........................................................................20

Course Load and Transcript .................................................................................20

The Role of High School Guidance Counselors ........................................................21

Job Description ....................................................................................................21

Role in the Application Process ...........................................................................21

Importance of Understanding College Admissions .............................................22

Summary of the Literature Review ............................................................................23

Chapter III: Methodology ................................................................................................25

Context of Study ........................................................................................................25

Population and Sampling ...........................................................................................33

Data Collection Instruments ......................................................................................34

Data Collection Procedures ........................................................................................36

Data Analysis .............................................................................................................37

Chapter IV: Findings ........................................................................................................38

Profile of the Sample: Guidance Counselors and Admission Counselors .................38

Analysis of the Data ...................................................................................................41

Research Question 1 ............................................................................................41

Research Question 2 ............................................................................................45

Research Question 3 ............................................................................................46

Chapter V: Summary, Discussion, Conclusions, and Recommendations .......................48

Summary of the Study ...............................................................................................48

Discussion of the Findings .........................................................................................48

viii!

!

Table of Contents (Continued)

Research Question 1 ............................................................................................48

Research Question 2 ............................................................................................50

Research Question 3 ............................................................................................51

Conclusions ................................................................................................................52

Recommendations for Practice ..................................................................................53

Recommendations for Further Research ....................................................................53

References ........................................................................................................................55

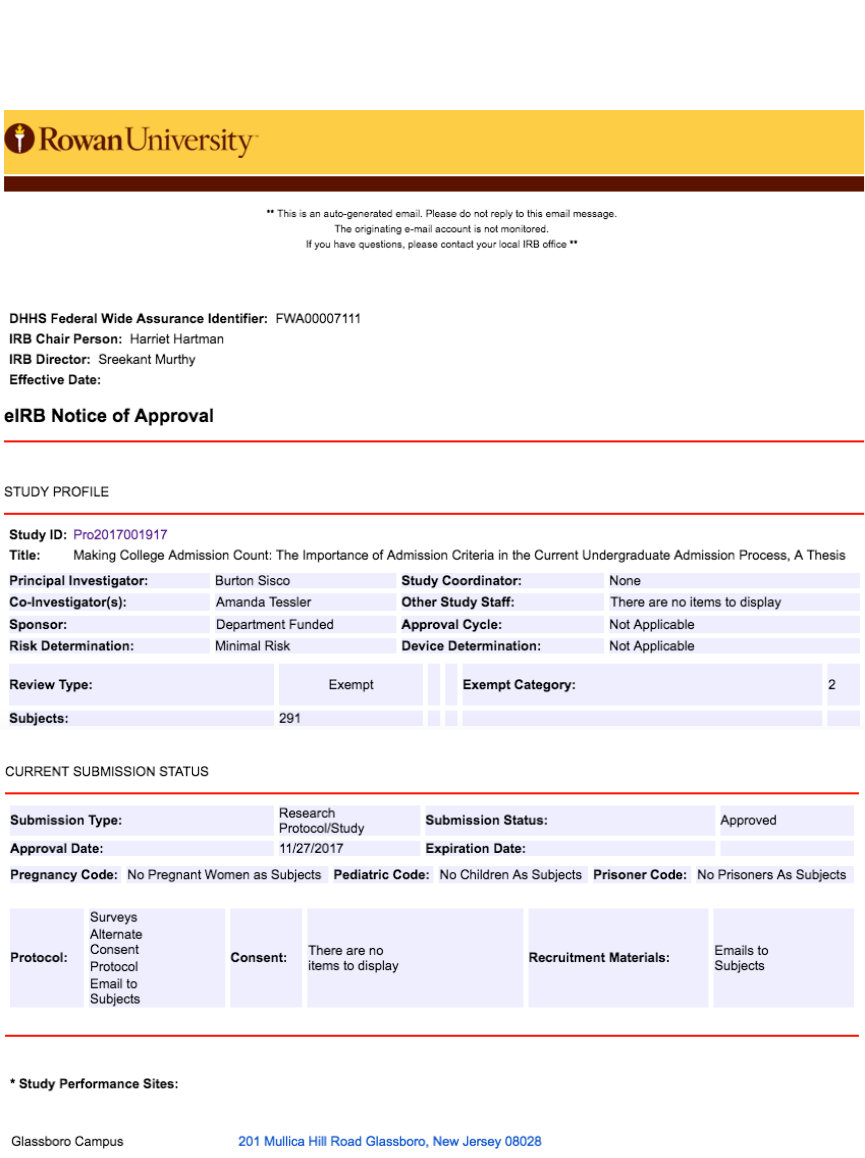

Appendix A: Institutional Review Board Approval ........................................................58

Appendix B: Initial Email to Potential Subjects ..............................................................59

Appendix C: Reminder Email to Potential Subjects ........................................................60

Appendix D: Online Alternate Consent Form .................................................................61

Appendix E: Survey for Admission Officers ...................................................................63

Appendix F: Survey for Guidance Counselors ................................................................65

ix!

!

List of Tables

Table Page

Table 3.1. Institutions Used for Data Collection .............................................................25

Table 3.2. School Districts Used for Data Collection with A-C DFG Rating .................26

Table 3.3. School Districts Used for Data Collection with D-F DFG Rating .................29

Table 3.4. School Districts Used for Data Collection with G-I DFG Rating ..................31

Table 4.1. Demographics of Guidance Counselors (N=232) ...........................................39

Table 4.2. Demographics of Admission Officers (N=47) ...............................................40

Table 4.3. Guidance Counselors' Attitudes Towards Admission Criteria (N=232) ........42

Table 4.4. Admission Officers' Attitudes Towards Admission Criteria (N=47) .............44

Table 4.5. Importance of Admission Criteria Means for Guidance Counselors and

Admission Officers ..........................................................................................46

Table 4.6. Read Any Past/Current SAT Research (N=279) ............................................47

Table 4.7. Belief of Which Criterion Best Predicts Academic Success (N=279) ............47

1

Chapter I

Introduction

The college admission process continues to evolve, adapt, and grow as the world

continues to change. Many requirements have held over the years, including standardized

test scores, letters of recommendation, and high school grade point average. However,

there is no consistent understanding of the importance of each of these requirements.

Each institution is different, whether it is public or private, small or large. Admission

offices and institutions look for different criteria in potential students. In order for high

school seniors to successfully navigate the collegiate admission process, they look to

their guidance counselors for advice.

Statement of the Problem

Since the types of institutions vary, each one operating and expecting different

standards from potential students, there is a common question of, “What are the most

important qualifications for a student to be accepted into a four-year institution?”

Guidance counselors in high schools are supposed to guide their students through the

college application process. However, since every institution weighs admission criteria

differently, consistency and knowledge about what criteria are the most important when

applying to college has declined.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to discover and compare the attitudes of selected

high school guidance counselors and college admission officers regarding the admission

criteria used in selecting college applicants. The study sought to focus on what is most

important for being accepted into an undergraduate program at a four-year public college

2

in New Jersey, as well as discovering the similarities and differences between the

attitudes of the subjects. The admission criteria selected were general requirements that

have a research and knowledge base on their predictability of first-year academic success.

Therefore, the goal of this study was to make the admission process easier to understand

for high school students in New Jersey.

Significance of the Study

This study looks to provide insight into the college admission process from the

perspectives of high school guidance counselors and admission officers. By discovering

the importance of admission criteria between these two subject groups, gaps in the

knowledge base can be closed. This can lead to more success for guidance counselors in

helping their students be accepted into a college in New Jersey by understanding the

admission process from the perspective of admission officers of these colleges.

Assumptions and Limitations

First, this study assumes that all subjects answered the survey fully and honestly,

based off of what is used in practice. A number of correlations may be found, but they

should not be used to generalize the population of high schools and higher education

institutions’ roles in college admissions. New Jersey high schools and colleges only

represent a small percentage of postsecondary institutions in the United States with

possible different standards of schools. The public-school system varies from state-to-

state and cannot be generalized. There also may be researcher bias since I worked as a

graduate intern in the Rowan University Admission’s Department during the time of the

study. This could have affected my understanding of the importance of varied admission

3

criteria and the admission process, as well as develop my own biases towards specific

criteria.

Operational Definitions

1. Academic Success: Meeting the institution’s expectations for students,

including retention and GPA.

2. Admission Officer: An employee of an institution’s Admissions Department

whose job is to recruit and select students to attend the institution.

3. Admission Requirements: Required criteria used to determine acceptance into

the institutions located in the state of New Jersey who were studied for this

research. This study looked at standardized test scores (SAT and ACT), high

school GPA, class rank, extracurricular activities, personal essays, letters of

recommendation, interviews, District Factor Grouping, and course load and

transcripts.

4. Guidance Counselor: An employee of a public New Jersey high school who

works in the high school’s guidance office and assists students in the college

application process.

5. Institution: A four-year public college or university in New Jersey that utilizes

an admissions department and a set of admission requirements to select their

students.

6. Qualitative Criteria: Requirements to submit to four-year institutions that focus

on personal qualities and characteristics. The qualitative criteria used in this study

were extracurricular activities, personal essays, letters of recommendation,

interviews, District Factor Grouping, and course load and transcripts.

4

7. Quantitative Criteria: Requirements to submit to four-year institutions that are

measurable. The quantitative criteria used in this study were standardized test

scores (SAT and ACT), high school GPA, and class rank.

8. Standards: Minimum and maximum requirements to be accepted into an

institution.

9. Student: A high school senior applying to a four-year college or university with

potential to attend the next year. The students referred to in this study were

seniors during the 2017-2018 school year in the state of New Jersey.

Important Acronyms

1. DFG: District Factor Grouping

2. FYGPA: First Year (of college) Grade Point Average

3. HSGPA: High School Grade Point Average

4. SATC: SAT Combined Score

5. SATM: SAT Math Score

6. SATV: SAT Verbal Score

7. SATW: SAT Writing Score

Research Questions

This study sought to explore three questions:

1. What are the most important admission criteria according to selected admission

officers and guidance counselors in New Jersey?

2. What similarities or differences are found between these two groups and their

attitudes towards current college requirements?

5

3. Do the subjects’ attitudes towards the chosen admission criteria correlate to the

literature on the predictability of student academic success?

Overview of the Study

Chapter II reviews relevant literature on current admission processes and

requirements in four-year institutions. The review looks at both quantitative and

qualitative admission criteria, including standardized tests, high school GPA, class rank,

extracurricular activities personal essays, letters of recommendation, interviews, District

Factor Grouping, and course load and transcripts. This chapter discusses each of the

criteria used in this study, including discussions on predictability of first-year college

academic success and the general uses of each of the criteria in the admissions process.

Chapter III describes the procedures and methodologies used in this study. In this

chapter are explanations of the target population and sample, explanations of the high

schools and colleges selected, data collection methods, instruments, and data analysis

measures.

Chapter IV presents the findings and results of the study. This chapter looks at the

results found and compares the findings to the initial research questions. This chapter also

looks at the demographics of the subjects.

Chapter V discusses the significant findings, offers conclusions, and discusses

suggestions for practice and further research.

6

Chapter II

Review of the Literature

Current Admissions Process and Requirements

The current college admission process varies from institution to institution.

Procedures are general among them, but the specific requirements and standards vary due

to competitiveness of each institution. Applications typically include an application form,

high school transcript, standardized test scores, letters of recommendation, and personal

essay. Admission departments look at these and other criteria submitted by an applicant

to make their admission decision. The criteria can be broken down into two categories:

quantitative and qualitative. The quantitative criteria are measurable requirements,

including grades and test scores. The qualitative criteria focus on personal qualities and

characteristics. These criteria include letters of recommendation, personal essays, and

interviews.

The varied admission criteria and standards stem from the differences in

importance of each of the admission criteria used by admissions officers and the

institution. Some admission officers believe that the quantitative criteria are most

important due to the research on predictability of student success, while others believe

that qualitative criteria show personal characteristics of a student that academic

performance may hide.

The National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC)

distributes their Admission Trends Survey (ATS) each year. The 2015 survey received 687

responses from institutions across the country, and collected data on application volume,

wait lists, Early Decision and Early Action, and most important factors in admission

7

decisions (National Association for College Admission Counseling [NACAC], 2016).

The criteria used most in admission decisions in Fall 2015, according to the institutions

surveyed, were high school grades and GPA, strength of curriculum, and standardized

test scores (NACAC, 2016).

Admissions departments often lean towards using either a formulaic or holistic

review process while making admissions decisions (Richmond, 2011; Tremblay, 2013).

A formulaic approach focuses on the quantitative admissions criteria of potential

students, which includes standardized test scores, high school GPA (HSGPA), and high

school class rank (McGinty, 2004). Often when using this approach, admissions officers

use a rubric or formula to make their admissions decision (Atkinson, 2001; McGinty,

2004). These rubrics and formulas have minimum and maximum scores that the applicant

must have to be accepted. Institutions pride themselves on raising their average scores

each year, by admitting more competitive students and raising their average test scores

and GPAs of incoming freshmen. Administrators in favor of this quantitative admissions

approach argue that research has shown that test scores, combined with grades, can

predict first-year academic success better than just grades alone (Zwick, 2007b).

A holistic approach to admissions decisions involves looking at more than simply

the candidate’s academic achievements, but takes into consideration both quantitative and

qualitative criteria of the applicant (Carlock, 2014; Gilroy, 2007; Hornberger, 2010;

Richmond, 2011). The criteria reviewed include extracurricular activities, including role

in the community and public service (Carlock, 2014). Institutions who use this approach

for admissions decisions look at these aspects of a student’s life as well as their academic

achievement and standardized test scores (Carlock, 2014). Looking at a potential

8

student’s application through a holistic perspective can “help all students, especially low-

income and minority students, determine their educational destinies” (Atkinson, 2001, p.

139). The holistic approach can help administrators understand an applicant’s character

and personal qualities as well as their academic potential.

Guidance counselors serve as a liaison between students and college admission. A

successful admission process relies on the assistance of high school guidance counselors.

One of the main responsibilities of a high school guidance counselor is assistance with

college applications (NACAC, 1990). Because of this, counselors need to know what

institutions, more specifically admission officers, are looking for in potential students.

Applicants need to be informed of what is most important to be accepted into an

institution, which is where guidance counselors come into play (Ishop, 2008). Multiple

studies have indicated that both admission officers and guidance counselors believe

academic factors were the most important in college admission criteria. However, they

did differ in their opinions on individual admission criteria (Gaitlin, 1997; Getler, 2007).

This study compares the importance of specific college admission criteria to

admission officers and high school guidance counselors. Quantitative and qualitative

admission criteria were included in this study. The quantitative criteria were standardized

testing, SAT and ACT scores, HSGPA, and class rank. The qualitative criteria were

extracurricular activities, personal essays, letters of recommendation, interviews, District

Factor Grouping (DFG), and course load and transcripts. This chapter discusses each of

the criteria used in the study, including discussions on predictability of first-year

academic success and the uses of each criterion in the admissions process.

9

Quantitative Admission Criteria

Standardized testing. Standardized testing for college admissions was first

established during the early twentieth century (Zwick, 2007b). During that time, there

were an abundance of entrance examinations that differed between institutions (Zwick,

2007b). In 1900, to try and standardize college admission testing, 12 leaders from the top

northeastern universities formed the College Entrance Examination Board (Zwick,

2007b). The SAT was first implemented in 1926 and, since then, has been praised for its

reliability and validity in predicting academic success in college freshmen (NACAC,

2016; Zwick, 2007b).

The SAT and ACT are the two most commonly used standardized tests.

According to the ATS survey, 78% of colleges who responded require either the SAT or

the ACT for admission with 3% requiring the SAT specifically (NACAC, 2016).

As of March 2016, the SAT was redesigned “to develop an assessment that better

reflects the work that students will do in college” (Shaw et al., 2016, p. 5). The

redesigned test includes three sections: reading and writing, math, and an optional essay

portion (Shaw et al., 2016). Both reading and writing and math sections are scored on a

200-800 scale with subscores on a 10-40 scale (Shaw et al., 2016). A validity study was

completed for the redesigned SAT in the fall of 2014 (Shaw et al., 2016). Because this

redesign is young, majority of research looked at in this review are prior to the 2016

redesign.

There were 1,681,134 students in the class of 2016 who took the SAT, either the

old or redesigned version, at least once through June 2016 (“Class of 2016 SAT Results,”

10

2016). While the SAT is used in more institutions for admission and seems to be more

common, 2,090,342 students of the class of 2016 took the ACT (ACT, Inc., 2016).

The ACT is broken up into four sections: English, Math, Reading, and Science

(“Help and FAQ’s,” 2017). Students who take this test receive a composite score of 1-36,

which is made up of their average from the four test scores (“Help and FAQ’s,” 2017).

Along with a composite score, test takers receive four more scores designed to represent

college readiness: Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) score, English

Language Arts (ELA) score, Progress Toward Career Readiness Indicator, and Text

Complexity Progress Indicator (“Help and FAQ’s,” 2017). The ACT test was designed to

measure academic achievement in the four sections, while the SAT focuses on reasoning

and definitions (“Help and FAQ’s,” 2017).

Standardized test scores predictability of first-year success. A significant amount

of research has suggested that SAT scores are valid and reliable predictors of first-year

GPA (FYGPA) in college (NACAC, 2016; Zwick, 2007b). An average correlation of

0.38 has been found between combined verbal and math SAT scores and FYGPA through

multiple research studies (Betts, 2011; Carlock, 2014; Zwick, 2007a). Zwick (2013)

suggests that 12-13% of the variance of first year GPA is attributed to SAT scores, and

21-22% of the variance is attributed to HSGPA and SAT scores combined.

The College Board conducted a validity test of the SAT in 2012 revealing a

stronger relationship between SAT scores and FYGPA with a correlation of .54 (Beard &

Marini, 2015). However, a stronger correlation of .61 was found when HSGPA was

added in (Beard & Marini, 2015). It is important to note that there may be bias in this

study, since The College Board, the organization responsible for the development and

11

distribution of the SAT, sponsored the research. Variance may be due to the

demographics of the sample; regions of the country sampled as well as undergraduate

enrollment were not equal (Beard & Marini, 2015). Variance may also be due to average

HSGPA of the sample as well as SAT scores (Beard & Marini, 2015). The mean HSGPA

was 3.62 with a standard deviation of 0.496 (Beard & Marini, 2015). The means of SAT

critical reading, SAT math, and SAT writing were 550, 571, and 544, respectively, with

standard deviations of 97.4, 99.7, and 99.5 (Beard & Marini, 2015).

Qualitative research has also suggested that there is predictability between

standardized test scores and academic success, but not all the time. However, the research

suggests the opposite of the quantitative criteria. Both admission officers and advisors

from Rowan University, based on their experience, believe that SAT scores do predict

academic success, however, they are only valid sometimes (Betts, 2011). These

administrators have often seen students with high SAT scores struggle in college and vice

versa (Betts, 2011). They recommended that SAT scores be given minimal weight when

making acceptance decisions (Betts, 2011).

Criticisms of the SAT. One criticism of standardized testing is how they are not

reliable for some students, i.e. students that come from a low-income family or a family

of low social economic status (SES) (Gilroy, 2007). Research has shown that there is a

positive correlation between family income and SAT scores: as family income increases,

so do SAT scores (Gilroy, 2007). Therefore, it is possible that socioeconomic status could

influence SAT and other standardized test scores (Gilroy, 2007).

It has also been noted that students with learning disabilities struggle with

standardized test taking; they are unable to successfully compete with other applicants

12

when comparing test scores (Betts, 2011).

Another criticism involves scholarship eligibility issues (Cohn, Cohn, Balch, &

Bradley, 2004; Gilroy, 2007). Research has suggested that nonwhite students are less

likely than their white counterparts to be eligible for scholarships if SAT scores are

required (Cohn et al., 2004). As for maintaining scholarships, “nonwhites are less likely

than whites, and males are less likely than females, to achieve the 3.0 GPA in college

required to maintain their scholarships” (Cohn et al., 2004, p. 585). Low socioeconomic

status may limit access to higher education due to standardized test bias (Gilroy, 2007).

SAT scores are more commonly becoming optional to submit during application because

of the likely bias against socioeconomic status (Betts, 2011; Cohn et al., 2004; Gilroy,

2007).

Even though research has suggested that the SAT is biased towards low SES

families and race/ethnicity, the College Board denies the bias (Letukas, 2015). Letukas

(2015) states how it is a fact that the positive correlation between higher SES status and

higher test scores is due to the rigorous course load in high school and not wealth.

Another fact discussed is that the SAT is not biased against some minority groups with

the reasoning being the rigorous pretest phase which determines which questions will be

used on the SAT (Letukas, 2015). If a question is biased during this phase to minority

groups, it will likely not be used in the final SAT (Letukas, 2015).

Another rumor discussed in the article addresses the problem of low predictability

of student achievement from SAT scores (Letukas, 2015). The fact discussed about this is

that the SAT is a “good predictor of first-year performance in college, student retention,

as well as cumulative college GPA” (Letukas, 2015, p. 3). It is then discussed that

13

HSGPA combined with SAT scores have an average correlation of .46 with first-year

college GPA, so both HSGPA and SAT scores should be used when assessing a student’s

application (Letukas, 2015). Much of the research disagrees with Letukas’ (2015) facts

(Cohn et al., 2004; Gilroy, 2007).

Uses of standardized testing in college admission. Past studies have looked at

admissions officers’ perspectives on the importance of SAT and ACT scores as

admission criteria. Gaitlin’s (1997) research indicated that both SAT and ACT scores

were second most important to admission officers and guidance counselors with HSGPA

being the most important. Admission officers averaged 4.67 on a five-point Likert-scale

for SAT scores, and 4.65 for ACT scores (Gaitlin, 1997). Guidance counselors averaged

4.48 on a five-point Likert-scale for SAT scores, and 4.05 for ACT scores (Gaitlin,

1997). Both subject groups agreed that standardized test scores were very important for

college admission. Getler (2007) surveyed admissions officers from four public

undergraduate institutions across New Jersey. It was discovered that 100% of subjects

responded that their institution believed standardized test scores were “most important”

or “very important” for admission (Getler, 2007).

Contrary to the research of the importance on SAT scores for college admission, a

study conducted by Betts (2011) suggested, through qualitative analysis, that assistant

directors of admissions at Rowan University believed SAT scores should hold minimum

weight when reviewing a potential student’s application. While some employees and

administrators believe that standardized test scores should hold minimum weight in an

applicant’s admission decision, research has shown that both admissions officers and

guidance counselors believe that they are the most important admission criteria (Gaitlin,

14

1997; Getler, 2007). The vast differences in the research calls for further research into the

usage of SAT scores in college admission.

High school GPA.

Predictability of high school GPA and first-year success. Quantitative research

has discovered an average correlation of 0.52 between HSGPA and FYGPA (Betts, 2011;

Carlock, 2014). This research suggests a stronger correlation between HSGPA and

FYGPA, yet institutions lean on SAT scores of potential students to make acceptance

decisions and identify their predicted success.

Use of high school GPA in college admission. Generally, HSGPA reflects the

strongest positive correlation with academic success and FYGPA in college (Betts, 2011;

Carlock, 2014; NACAC, 2016). Admission officers also look at grades throughout the

four years of high school, which includes growth and progress as well as course load

(Betts, 2011; McGinty, 2004).

Gaitlin’s (1997) study indicated that HSGPA was the most important admission

criteria to both admission officers and guidance counselors. Admission officers and

guidance counselors averaged 4.72 and 4.58 on a five-point Likert-scale, respectively

(Gaitlin, 1997). It was also discovered that guidance counselors believed HSGPA and

course selection better predicted college success, with SAT and ACT scores near the

bottom of the list (Betts, 2011).

Class rank. High school class rank has been defined as a “percentile rating of

academic placement in the high school graduating class,” (Nack & Townsend, 2007, p.

69). The student with the highest HSGPA is listed first, and the student with the lowest

HSGPA listed last (Nack & Townsend, 2007).

15

Class rank can be used to compare students from different schools and different

grading curves (NACAC, 2016). Using class rank as an admission criterion has become

increasingly less important over the past few years (NACAC, 2016). However, it is still

commonly used as a requirement for admission (NACAC, 2016).

There are many problems when using class rank to make an admission decision.

First, each year, fewer high schools are publicly sharing class rank (NACAC, 2016).

Because of this, many students’ class ranks can only be estimated, making the criterion

difficult to compare between applicants (NACAC, 2016).

Second, it has been found that high school class rank adds nothing to the

predictability of college success (Nack & Townsend, 2007). This is possibly due to how

class rank is established in each school district; it is almost impossible to compare a

student who has ranked first in their graduating class with a HSGPA of 3.23 and a student

who has ranked first with a 4.0 HSGPA (Nack & Townsend, 2007). Rank does not

represent an individual student’s HSGPA, but a student’s HSGPA compared to students

they graduated with (Nack & Townsend, 2007).

Gaitlin’s (1997) study indicated a significant difference between admission

officers and guidance counselors’ attitudes towards class rank. Admission officers

averaged 1.8 on a five-point Likert-scale, while guidance counselors averaged 4.11

(Gaitlin, 1997). This discrepancy calls for further research on the topic to make sure all

counselors are on the same page.

Qualitative Admission Criteria

Even though there is a general emphasis on academics and quantitative criteria for

college admission, many other criteria are used for admission decisions and required in

16

an admission application, In the literature, qualitative admission criteria are described as

personal qualities used to assess personal qualities and the character of an applicant

(Ishop, 2008). These criteria are used to get to know an applicant by more than just

numbers. Some of these criteria include extracurricular activities, personal essays, letters

of recommendation, interviews, District Factor Grouping (DFG), and course load and

transcripts.

Extracurricular activities. Extracurriculars are activities where participation

from students is outside of the classroom. These activities can be personal, community, or

school related. Extracurricular activities have been shown to have many benefits for

students, including development of social, academic, and intellectual skills (Lawhorn,

2008). Research suggests that involvement in extracurricular activities boosts students’

academic performances (Lawhorn, 2008). This leads to self-motivation, leadership, and

time management skills, as well as responsibility; all of these leading to higher grades

and HSGPAs (Lawhorn, 2008). Admission officers look for these qualities when

reviewing applications to predict retention, commitment, and leadership. Having

extracurricular activities on an application can help students stand out from other

applicants.

Predictability. Some research has suggested that participation in extracurricular

activities while in high school leads to a greater likelihood in high education enrollment

compared to joining the workforce or enlisting in the military (Martin, 2015). Data have

also suggested that the students with the highest test scores actively engage in

extracurricular activities (Kronholz, 2012). Benefits from participating in extracurricular

17

activities, such as higher grades, time management skills, and self-motivation, increases

the odds for students being admitted to college (Lawhorn, 2008; Martin, 2015).

However, results from the ATS survey suggested that few colleges found either no

correlation or small positive correlations between the relationship of extracurricular

activities to college academic achievement (NACAC, 2016). Findings are often

inconclusive or inconsistent when researching extracurriculars; some researchers believe

that there is only a low correlation between extracurriculars and academic success, while

others insist that there is a strong relationship (Kronholz, 2012).

Use in admissions. Extracurricular activities were seen as an indicator of time

management skills according to assistant directors of admissions at Rowan University

(Betts, 2011). As stated earlier, students who engage in extracurricular activities are more

likely to develop social, intellectual, and academic skills, all important characteristics that

admission officers look for in an applicant (Lawhorn, 2008; Martin, 2015).

Extracurricular activities may also show admission officers perseverance and

commitment, which, as some admission officers noted, may bump them from being on a

wait-list to being accepted (Richmond, 2011).

Personal essays. Personal essays, also referred to as college essays or admission

essays, are essays written by students from a prompt or question given by the institution.

Many schools require these as part of the application, while others list them as optional.

The undergraduate admissions process uses essays to evaluate writing ability and

characteristics (Ishop, 2008); these essays are comparable to personal statements used for

graduate admissions. The undergraduate admissions essays are writing samples that often

lead with a prompt and are generally about the applicant’s interests, personal goals, and

18

academic goals (Ishop, 2008). Admission officers use these essays as evidence of

creativity, intellect, and to assess writing skills (Ishop, 2008).

Ishop (2008) considered what students wrote in their college admission essays.

The analysis found that these students wrote essays with a focus on academic

opportunities, careers and jobs, travel, religion, moving, activities, family, coping with

adversity, and coping with illness and death (Ishop, 2008). Applicants wrote about these

topics and how they related to characteristics about themselves (Ishop, 2008). The essays

displayed personal qualities potential students wanted to show admission officers that

they felt would help them be accepted into the institution (Ishop, 2008).

However, there is a very small correlation between personal essays and school

performance, especially if prior grades are available (Murphy, Klieger, Borneman, &

Kuncel, 2009). Essays are not useful in predicting academic success, but can be used for

other purposes, including matching a student to an advisor or determining if the student

needs remedial programs (Murphy, Klieger, Borneman, & Kuncel, 2009).

Letters of recommendation. Letters of recommendation, in admission

applications, are written letters from an individual who can speak about the student from

personal experience. These letters are used to assess a student’s performance in school, at

work, or other outside activities through the perspective of someone else rather than

grades.

Research has indicated that there is a significant difference between the attitudes

towards recommendations between admission officers and guidance counselors (Gaitlin,

1997). Guidance counselors believed recommendations are given a higher weight than

19

admission officers, who give little weight to recommendations in practice (Gaitlin, 1997;

Getler, 2007).

Interviews. Interviews are occasionally conducted for applicants to get to know

them and how they hold themselves. There are two types of admission interviews that

may be conducted: informational or evaluative (“Admission Interview Tips,” n.d.).

Informational interviews are used to inform the potential student about the institution,

while evaluative interviews are used to assess the student, which then becomes a part of

the student’s application file (“Admission Interview Tips,” n.d.). While interviews seem

important and necessary to the admission process, only a handful of colleges require them

for undergraduate admissions. Interviews are seen more in graduate and doctoral settings,

especially medical schools, as well as for special admissions programs (Betts, 2011).

In a study on undergraduate admission interviews, admission officers focused on

motivation and oral communication to assess a student in an interview (Shahani,

Dipboye, & Gehrlein, 1991). Persistence in extra-curricular activities, academic

challenge, reading interests, interest in external affairs, overcoming handicaps and

hardships, overall confidence and energy, and an overall motivation were all used to

assess motivation (Shahani, Dipboye, & Gehrlein, 1991). Use of proper grammatical

structure, range of vocabulary, organization and coherence of discourse, intensity and

enthusiasm of discourse, and an overall oral communication rating were used to assess

oral communication (Shahani, Dipboye, & Gehrlein, 1991). In this study, low

correlations were found between a student’s paper credentials and interview evaluations,

suggesting that the interview found different information that was already given on paper

credentials (Shahani, Dipboye, & Gehrlein, 1991).

20

It is important to note that interviews are subjective and not always valid; an

interviewer may bring bias to the interview and give the interviewee lower scores based

on outside factors.

District Factor Grouping (DFG). When admission officers look at the

quantitative criteria of a student they take into consideration the high school and district

he or she attended (McGinty, 2004). New Jersey gives each district a District Factor

Grouping (DFG) score. These scores are used to measure a community’s approximate

socioeconomic status (SES) (“District Factor Groups (DFG) for School Districts,” 2000).

Six variables are used to develop each town’s score: percent of adults with no high school

diploma, percent of adults with some college education, occupational status,

unemployment rate, percent of individuals in poverty, and the median family income

(“District Factor Groups (DFG) for School Districts,” 2000). Communities can be ranked

from A-J, lowest to highest, respectively (“District Factor Groups (DFG) for School

Districts,” 2000).

Course load and transcript. Transcripts show the grades of students and their

course load over four years of high school. It also shows four years of growth, progress,

and perseverance (Betts, 2011; McGinty, 2004). Honors and Advanced Placement class

grades can provide insight on these characteristics and college readiness, as well.

Admission officers will look at course load as a factor of academic success both

in high school and possibly in college (McGinty, 2004). McGinty (2004) gives examples

of this, explaining how a “grade of B in Advanced Placement English is more important

than an A in chorus,” and “an A in chemistry carries more weight than an A in civics,”

(p. 6).

21

When interviewed, Rowan University admission officers said that they believed

high school transcript, including grades, course, and four-year performance, are a better

predictor of college success compared to SAT scores (Betts, 2011).

The Role of High School Guidance Counselors

Job description. NACAC’s Statement on Precollege Guidance and Counseling

and the Role of the School Counselor (1990) defines precollege guidance counseling as

activities that help students pursue challenging curriculum that results in more higher

education options, identify requirements for college access for students, and assist in

financial aid, college decisions, and other processes of the college application and

admission process.

The Counseling Trends Survey (CTS), administered by the NACAC in 2014,

collected information from high school guidance counselors about their work priorities

and responsibilities relating to the college admission and transition process (Clinedinst,

Koranteng, & Nicola, 2015). A total of 1,360 responses were collected (Clinedinst et al.,

2015). Two statements that the counselors responded to relating to the college admission

process were, “Advice and education for students and families on standardized testing,”

and “Actively represent students to college admission officers” (Clinedinst et al., 2015, p.

28). For the first statement, 30% answered frequently, 43% occasionally, 26%

infrequently, and 2% never (Clinedinst et al., 2015). For the second statement, 41%

responded frequently, 33% occasionally, 21% infrequently, and 5% never (Clinedinst et

al., 2015).

Role in the application process. Guidance counselors serve as the liaison

between high school and college. It is necessary for these counselors to not only

22

understand the admission process, but also the criteria that are most important for being

accepted into a higher education institution (Gaitlin, 1997; Ishop, 2008). Guidance

counselors are required to understand current admission requirements as part of their job

to help students with college applications and college selection and the application

process (NACAC, 2000). They are to help their students through the selection process by

identifying where he or she has the best chance of being successful (Trembly, 2013).

Guidance counselors’ main role is to “guide” their students through the college

application process.

Importance of understanding college admissions. Because guidance counselors

play such a large role in the college application process, it is key that they understand the

current practices of admissions (Gaitlin, 1997). Research consistently shows that high

school counseling is an area of concern, and addresses the need for improvement for

students to successfully be admitted into college (Richmond, 2011). Research also

suggests that communication between admission officers and guidance counselors needs

improvement so guidance counselors give the most accurate and up-to-date information

about college admissions to their students (Gaitlin, 1997; Ishop, 2008). Studies have

suggested that the two groups do not agree on what is most important in college

admissions. Many admission professionals report having negative experiences with

guidance counselors (Gaitlin, 1997; Richmond, 2011). It is likely that guidance

counselors are putting an emphasis on criteria that admission officers do not put much

consideration into when reviewing applications (Gaitlin, 1997). Ultimately, admission

officers are experts on what institutions are looking for in a student and this information

needs to properly be funneled to applicants (Ishop, 2008).

23

Demographic data have suggested that college admission officers are younger,

with less experience and less education than guidance counselors (Gaitlin, 1997). It is fair

to question whether this influences the admission process. Do guidance counselors differ

from admission officers in their attitudes towards the importance of admission criteria

because they have been in their field for a longer amount of time? Are they set in their

ways or is there a communication issue? It would be interesting to see if any of these

factors are related.

Summary of the Literature Review

The literature reveals that quantitative criteria seem to be favored over qualitative

requirements when it comes to predicting college academic success. These quantitative

criteria have extensive research that shows the connections between the numbers and

prediction of college success, which seems to be why they are favored in the admission

process.

Much more research was found on quantitative criteria than qualitative measures.

Only a handful of studies were found on qualitative criteria enrollment and predictability

of academic success.

Research continues to be contradictory on what are the best predictors of college

success, as well as what admission criteria are the most important (Betts, 2011; Carlock,

2014; Getler, 2007; Zwick, 2007a). There are only a handful of studies that look into both

admission officers and guidance counselors. The ones that do look into both groups find

that quantitative criteria are favored among importance for admission criteria, but are not

favored as far as predictability on academic success in college.

24

In order for students to be successful in their college application process and

college career, high school guidance counselors need to understand the current admission

process and what admission officers are looking for in a potential student.

There is a paucity of research in New Jersey that looks at admission criteria from

the perspective of admission officers and guidance counselors. My research also looks at

demographics and region a student is from as a criterion for admission. My research can

be used to help guidance counselors in New Jersey understand the essential criteria

needed to be accepted into the state’s institutions based on the attitudes of employees

from these institutions. Ultimately, this will help future students in New Jersey apply for

college by knowing exactly what admission officers are looking at in their application.

25

Chapter III

Methodology

Context of Study

This study was conducted at various public high schools and public four-year

institutions in New Jersey. All of the high schools and institutions chosen for this study

were located in New Jersey. Four-year colleges were chosen based on similarity; each of

the institutions were four-year public schools located in New Jersey with similar missions

and backgrounds.

The institutions included in this study were New Jersey City University, Kean

University, Montclair University, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Ramapo College

of New Jersey, Rowan University, Stockton University, The College of New Jersey, and

William Patterson University. Table 3.1 describes each institution contacted for this study

including number of admission counselors for each institution.

Table 3.1

!

Institutions Used for Data Collection

Institution

Number of Admission Counselors*

New Jersey City University

22

Kean University

8

Montclair University

13

New Jersey Institute of Technology

8

Ramapo College of New Jersey

8

Rowan University

11

Stockton University

9

The College of New Jersey

9

William Patterson University

10

Note. *Counselors include those with the title of counselor and higher

26

High schools were chosen randomly by District Factor Grouping (DFG). As

described in Chapter II, DFG is a score used to measure approximate socioeconomic

status (SES) of a community (“District Factor Groups (DFG) for School Districts,”

2000). The scores range from A to J, lowest to highest, respectively (“District Factor

Groups (DFG) for School Districts,” 2000). Communities who are scored A rank as a low

SES community, while communities who are scored J rank as a high SES community.

Districts were sorted into three groups: A-C, D-F, and G-I. After being sorted, 25% of

each group was selected using a random number generator. Forty-five districts were

chosen for both the A-C and D-F group, and 52 districts were chosen for the G-I group. A

contact list of guidance counselors and admission officers was compiled through high

school and institutional websites. Emails addresses for data collection were found

through these websites.

Table 3.2 describes the districts with DFG scores from A-C. The table describes

each district including the DFG scores, the high school that students attend, and how

many guidance counselors the school has.

Table 3.2

School Districts Used for Data Collection with A-C DFG Rating

District

Attending High School

DFG*

Number of

Guidance

Counselors

City of Orange Twp

Orange High School

A

3

Elsinboro Twp

Salem High School

A

4

Fairview Boro

Cliffside High School

A

5

Millville City

Memorial High School &

Millville High School

A

6

Mine Hill Twp

Dover High School

A

5

27

Table 3.2 (continued)

District

Attending High School

DFG*

Number of

Guidance

Counselors

Penns Grove Carneys Point

Penn Grove High School

A

4

Quinton Twp

Salem High School

A

4

Trenton

Trenton High School Main

Campus & Trenton High School

West Campus

A

10

Vineland City

Vineland High School

A

8

Washington Township

(Burlington County)

Cedar Creek High School

A

5

West New York

Memorial High School

A

6

Wildwood City

Wildwood High School

A

2

Woodbine Boro

Middle Township High School

A

3

Bellmawr Boro

Trinton High School

B

8

Berkeley Twp

Central Regional High School

B

6

Beverly City

Palmyra High School

B

2

Carteret Boro

Carteret High School

B

4

Cumberland Regional

Cumberland Regional High

School

B

5

Deerfield Twp

Cumberland Regional High

School

B

5

Glassboro

Glassboro High School

B

3

Gloucester City

Gloucester City Junior-Senior

High School

B

4

Greenwich (Warren)

Phillipsburg High School

B

5

Island Heights

Central Regional High School

B

6

Passaic County Manchester

Manchester Regional High

School

B

4

Riverton

Palmyra High School

B

2

Waterford Twp

Hammonton High School

B

5

Weymouth Twp

Buena Regional High School

B

3

Barnegat Twp

Barnegat High School

CD

5

Bayonne City

Bayonne High School

CD

11

Carlstadt-East Rutherford

Henry P. Becton Regional High

School

CD

2

Clayton Boro

Clayton High School

CD

3

28

Table 3.2 (continued)

District

Attending High School

DFG*

Number of

Guidance

Counselors

Clifton City

Clifton High School

CD

12

Elmwood Park

Elmwood Park Memorial High

School

CD

2

Gateway Regional

Gateway Regional High School

CD

5

Greater Egg Harbor

Absegami High School, Cedar

Creek High School, & Oakcrest

High School

CD

15

Hackensack City

Hackensack High School

CD

7

Keyport Boro

Keyport High School

CD

3

Manville Boro

Manville High School

CD

2

Merchantville

Pennsauken High School

CD

5

Monroe Twp (Gloucester)

Williamstown High School

CD

8

Pemberton Borough

Pemberton Township High

School

CD

6

Pennsville

Pennsville High School

CD

3

South Hackensack Twp

Hackensack High School

CD

7

Union Beach

Keyport High School

CD

3

Weehawken Twp

Weehawken High School

CD

3

Wenonah Boro

Gateway Regional High School

CD

5

Woodbury Heights

Gateway Regional High School

CD

5

Note. *DFG rating is based off of 2000 Decennial Census

Table 3.3 describes the school districts with DFG scores from D-F. The table

describes each school district including the DFG scores, the high school that students

attend, and how many guidance counselors the school has.

29

Table 3.3

School Districts Used for Data Collection with D-F DFG Rating

District

Attending High School

DFG*

Number of

Guidance

Counselors

Allamuchy

Hackettstown High School

DE

3

Belvidere Town

Belvidere High School

DE

2

Butler Boro

Butler High School

DE

3

Eastampton Twp

Rancocas Valley Regional High

School

DE

8

Frankford Twp

High Point Regional High

School

DE

5

Franklin Twp

Franklin High School

DE

8

Gloucester Twp

Black Horse Pike Regional

High School

DE

11

Hardyston Twp

Wallkill Valley HS

DE

3

Harmony Twp

Belvidere High School

DE

2

Lakehurst Boro

Jackson Liberty High School

DE

8

Longport

Ocean City High School

DE

5

Montague Twp

High Point Regional High

School

DE

5

Mount Ephraim Boro

Audubon High School

DE

3

North Arlington Boro

North Arlington High School

DE

2

North Plainfield Boro

North Plainfield High School

DE

4

Ocean City (Cape May)

Ocean City High School

DE

5

Ridgefield Park Twp

Ridgefield Park Jr./Sr. High

School

DE

4

Sayreville Boro

Sayreville War Memorial High

School

DE

7

Sea Isle City

Ocean City High School

DE

5

Sterling

Sterling High School

DE

5

Toms River Regional

High School East, High School

North, & High School South

DE

17

West Deptford Twp

West Deptford High School

DE

5

Westampton

Rancocas Valley Regional High

School

DE

8

Bergenfield

Bergenfield High School

FG

5

30

Table 3.3 (continued)

District

Attending High School

DFG*

Number of

Guidance

Counselors

Bordentown Regional

Bordentown Regional High

School

FG

3

Cinnaminson Twp

Cinnaminson High School

FG

4

Hoboken City

Hoboken High School

FG

3

Hopatcong

Hopatcong High School

FG

4

Little Falls Twp

Passaic Valley Regional High

School

FG

6

Mantoloking

Point Pleasant Beach High

School

FG

2

Middlesex Boro

Middlesex High School

FG

3

Ocean Twp (Monmouth)

Ocean Township High School

FG

5

Ocean Twp (Ocean)

Southern Regional High School

FG

9

Old Bridge Twp

Old Bridge High School

FG

12

Pompton Lakes Boro

Pompton Lakes High School

FG

4

Sea Bright Boro

Shore Regional High School

FG

3

South Plainfield Boro

South Plainfield High School

FG

4

Totowa Boro

Passaic Valley Regional High

School

FG

6

Warren Hills

Warren Hills Regional High

School

FG

5

Washington Twp

(Gloucester)

Washington Township High

School

FG

11

West Amwell Twp

South Hunterdon Regional High

School

FG

2

Woodstown-Pilesgrove

Regional

Woodstown High School

FG

4

Note. *DFG rating is based off of 2000 Decennial Census

Table 3.4 describes the districts with DFG scores from G-I. The table describes

each district including the DFG scores, the high school that students attend, and how

many guidance counselors the school has.

31

Table 3.4

School Districts Used for Data Collection with G-I DFG Rating

District

Attending High School

DFG*

Number of

Guidance

Counselors

Barrington Boro

Haddon Heights High School

GH

4

Delaware Valley Regional

Delaware Valley Regional High

School

GH

5

Emerson Boro

Emerson Junior-Senior High

School

GH

2

Freehold Twp

Freehold Township High

School

GH

9

Frenchtown Boro

Delaware Valley Regional High

School

GH

5

Hanover Park

Hanover Park High School

GH

4

Hanover Twp

Whippany Park High School

GH

4

Harrison Twp

Clearview Regional High

School District

GH

6

Kingwood Twp

Delaware Valley Regional High

School

GH

5

Lawrence Twp

Lawrence High School

GH

4

Leonia Boro

Leonia High School

GH

3

Manasquan Boro

Manasquan High School

GH

5

Medford Twp

Shawnee High School

GH

7

Milford Boro

Delaware Valley Regional High

School

GH

5

Millstone

Allentown High School

GH

5

Monmouth Regional

Monmouth Regional High

School District

GH

5

Netcong

Lenape Valley Regional High

School

GH

4

Piscataway Twp

Piscataway High School

GH

11

Roosevelt Boro

East Windsor Regional High

School

GH

2

Rutherford Boro

Rutherford High School

GH

4

South Belmar

Manasquan High School

GH

5

Spring Lake Heights Boro

Manasquan High School

GH

5

32

Table 3.4 (continued)

District

Attending High School

DFG*

Number of

Guidance

Counselors

Voorhees Twp

Eastern Regional High School

GH

9

Alpine Boro

Tenafly High School

I

7

Bedminster Twp

Bernards High School

I

4

East Amwell Twp

Hunterdon Central High School

I

16

Essex Fells Boro

West Essex Regional High

School

I

6

Franklin Lakes Boro

Ramapo High School & Indian

Hills High School

I

12

Glen Ridge Boro

Glen Ridge High School

I

3

Hampton Boro

Voorhees High School

I

6

Harding Township

Madison High School

I

4

Hillsborough Twp

Hillsborough High School

I

11

Hillsdale Boro

Pascack Valley High School

I

6

Lebanon Twp

North Hunterdon High School

I

8

Long Hill Twp

Watchung Hills Regional High

School

I

10

North Caldwell Boro

West Essex Regional High

School

I

6

Northern Valley Regional

Northern Valley Demarest &

Northern Valley Old Tappan

I

13

Oakland Boro

Ramapo High School & Indian

Hills High School

I

12

Pascack Valley Regional

Pascack Hills High School &

Pascack Valley High School

I

10

Readington Twp

Hunterdon Central High School

I

16

Roseland Boro

West Essex Regional High

School

I

6

South Brunswick Twp

South Brunswick High School

I

10

Summit City

Summit High School

I

8

Union Twp

North Hunterdon High School

I

8

Verona Boro

Verona High School

I

4

Washington Twp (Morris)

West Morris Central High

School

I

6

33

Table 3.4 (continued)

District

Attending High School

DFG*

Number of

Guidance

Counselors

West Essex Regional

West Essex Regional High

School

I

6

Bernards Twp

Ridge High School

J

9

Boonton Town

Mountain Lakes High School

J

6

Haddonfield Boro

Haddonfield Memorial High

School

J

5

Rumson Boro

Rumson-Fair Haven Regional

High School

J

5

Upper Saddle River Boro

Northern Highlands Regional

High School

J

6

Note. *DFG rating is based off of 2000 Decennial Census

Since the study focused on undergraduate admissions, community colleges were

not included for this study because they generally have an open enrollment admissions

practice. Medical schools were also not included since they award professional degrees.

Lastly, only public high schools and institutions were studied since they are funded by

the New Jersey government, and are similar in nature.

Population and Sampling

The target population of this study was all high school guidance counselors and

admission officers located in New Jersey. The sample for the study was a combination of

a convenience sample, purposive sample, and random sampling of the high school

guidance counselors from selected high schools in New Jersey, as well as admissions

officers working for selected four-year institutions.

There are approximately 1,200 members of the NJACAC, the New Jersey

Association for College Admission Counseling, which includes both guidance counselors

34

and admission professionals all from schools in New Jersey (“About NJACAC,” 2017).

A sample size calculator was used to get the sample size, with a confidence level of 95%

and 3% error rate. After reviewing public school websites and their guidance department

webpages, approximately 600 guidance counselors were employed in 142 school

districts, which only represents about 25% of public school districts in New Jersey. Thus,

the sample size was 698, including 600 guidance counselors and 98 admissions

counselors from the selected public four-year institutions. The desired sample size was

489 subjects, and would be made up of 420 guidance counselors, and 69 admission

counselors, 70% of the sample, respectively. The more realistic sample size would be

made up of 300 guidance counselors and 49 admissions counselors, 50% of the sample,

respectively. More guidance counselors were included in data collection and since more

public-school districts were included in the study compared to public four-year

institutions: this represents the New Jersey education system with more public-school

districts than public four-year institutions.

Both guidance counselors and admission officers were recruited through email.

Email addresses were compiled through high school and institutional websites available

publicly. The professionals were emailed an initial email on January 2

nd

, 2018 (Appendix

B), followed by reminder emails (Appendix C) every week to those who have not

responded to the survey; this is a feature on Qualtrics and the principal investigator and

co-investigator did not know who had and had not answered.

Data Collection Instruments

Two separate surveys were developed; one to distribute to admission officers of

the selected institutions (Appendix E) and one to distribute to guidance counselors of the

35

selected institutions (Appendix F). The surveys were developed through knowledge of

the database, mainly looking at Getler’s (2007) instruments for guidance

recommendation. Drafts of the survey were distributed to guidance counselors and

admission officers to test validity and reliability, as well as higher education

professionals. The professionals looked at the drafts and gave feedback on content,

grammar, and comprehension to establish face validity. A Cronbach Alpha was

calculated through SPSS after data collection was complete to determine the reliability of

the Likert-scale portion of the survey. After running the Cronbach Alpha test for the

Likert-scale section, the Alpha coefficient was .0588. This is a low internal reliability,

making the survey only slightly reliable; however, this is likely due to a small sample size

and a low number of items on the survey.

Two different surveys were distributed, one with wording suited towards

admission officers (Appendix E), and the other with wording relevant towards guidance

counselors (Appendix F). The survey used consisted of three sections: demographics,

Likert-scale items, and open-ended questions. The first section asked about the subjects’

background, including educational and employment background. The second section

used a Likert-scale format designed to probe subjects to choose 1-5, not important to

most important, on their opinion of how important each of the selected admission criteria

are for a high school senior to be accepted into a four-year institution.

The last section was two open-ended questions, the first question asking subjects

to list their opinion on the two most important criteria. The second open-ended question

asked to see if there were any differences between the opinion on the most important

admission criteria and which one best predicts academic success based on contradictions

36

of previous research. Both open-ended questions had drop down menus on Qualtrics to

make data analysis easier. Guidance counselors and admission officers answered the

open-ended questions by choosing their answer from a given list.

Alternate consent was used for subjects. Since it was not possible to receive

signatures from each subject, the individuals who voluntarily complete the survey

consented to an alternative consent (Appendix D), located before the survey began.

Data Collection Procedures

Before any data were collected, the Institutional Review Board application was

completed and approved. Following approval on November 27

th

, 2017 from Rowan

University’s Institutional Review board (Appendix A), data collection began.

A convenience sample was used to select public high schools used in the study.

Since District Factor Grouping (DFG) was a variable in the study, all public-school

districts in New Jersey were sorted into three groups: A-C, D-F, and G-I. After being

sorted, 25% of each group was selected using a random number generator. Forty-five

districts were chosen for both the A-C and D-F group, and 52 districts were chosen for

the G-I group. Four-year colleges were chosen based on similarity; each of the

institutions are four-year public schools located in New Jersey with similar missions. A

contact list of guidance counselors and admission officers was compiled through high

school and institutional websites. Emails addresses for data collection was found through

these websites.

The survey items were formatted and designed using Qualtrics, an online survey

development program, which collects and organizes data and results. The surveys were

distributed via email to the selected admission officers and guidance counselors from the

37

participating schools. The emails included an explanation of the study, as well as a link to

complete the survey (Appendix B; Appendix C). The email addresses of the subjects

were found on both institutional websites and school district websites.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(SPSS) software and Microsoft Excel. Data from incomplete surveys were not used; only

finished surveys were included in data analysis. Incomplete surveys were defined as

surveys that were less than 50% complete, meaning the subjects had to complete at least

nine questions. Seventeen surveys were removed from data analysis due to incompletion.