Affordable

Housing

in Ghana

SECTOR STUDY

List of abbreviations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Executive summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Research approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Views on affordable housing. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Understanding Ghana’s housing and demand . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Trends in types of housing (2000 to 2014) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Housing materials (external walling). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Housing types by occupancy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Housing tenure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Estimated market volume for affordable housing in Ghana . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Interesting areas for affordable housing. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Affordable housing interventions in Ghana . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

State and quasi-state interventions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Non-state housing interventions – housing cooperatives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Tema Housing Cooperative (THC) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Private sector interventions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Blue Rose Ltd . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Tamale Affordable Housing Project . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

TAMSUF Affordable Housing Project in Ashaiman Municipality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Addressing the challenges of affordable housing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Size of the affordable housing market . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

The housing value chain. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Home extension, improvement and completion schemes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Maintenance and retrofitting. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Construction of new units . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Standardisation of labour and local building materials. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Matrix of business opportunities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Strategies for affordable housing delivery. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Labour and materials . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Land supply and location. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Financing. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Urban infrastructure and municipal services. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

CONTENT

Customer and value proposition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Financing mechanisms available for affordable housing . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Self-financing. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Loans from informal borrowing, non-financial institutions and banks . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Mortgages from banks and non-bank institutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Remittances. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

46

Public budgetary allocations, subsidies and collaborative efforts . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Key stakeholders in the affordable housing market . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Annex 1: Available Literature on Housing in Ghana . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Annex 2: Housing interventions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

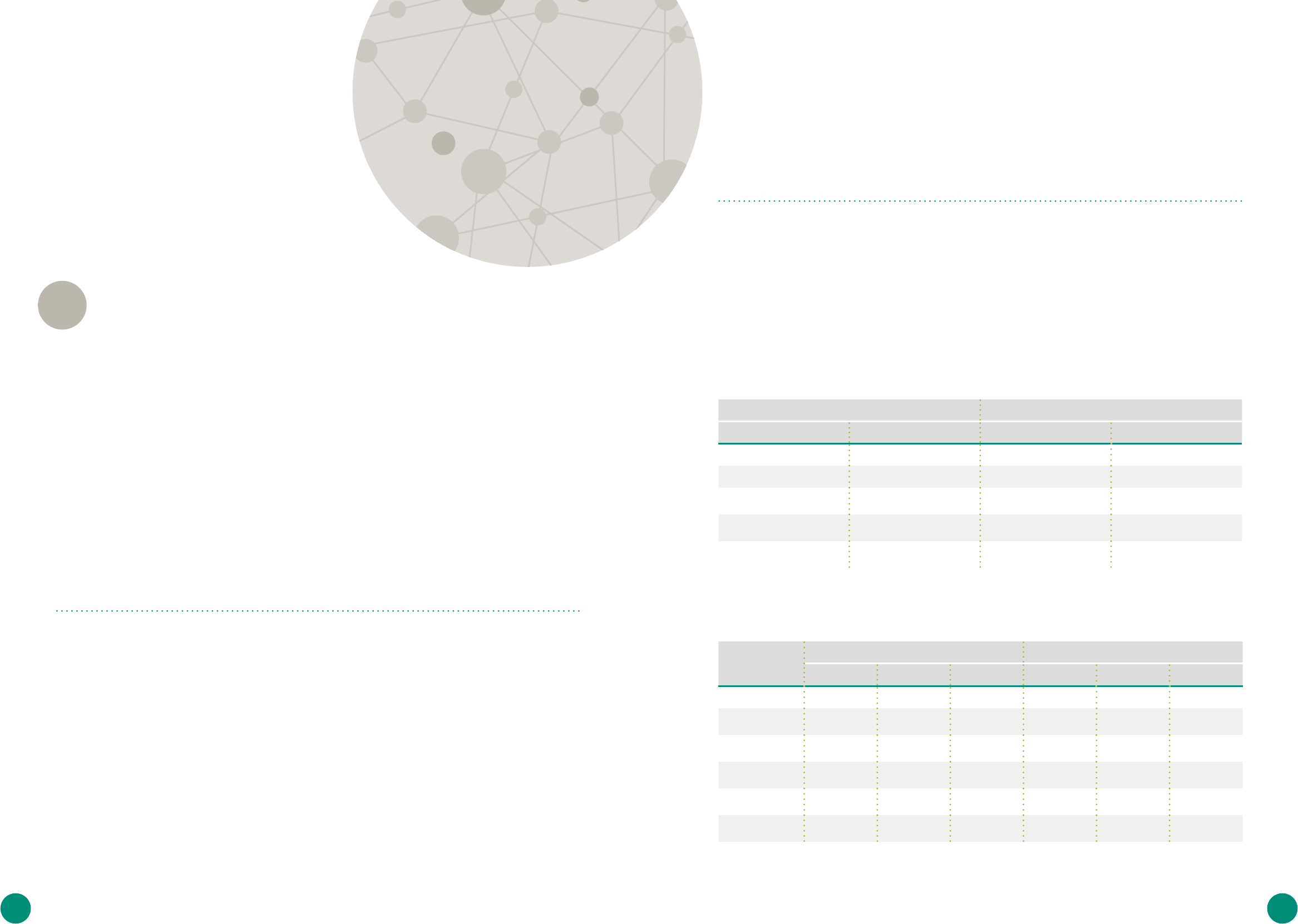

The Inclusive Business Action Network

(IBAN) promotes inclusive business

globally – by supporting the scale and

replication of inclusive business mo-

dels and engaging all different types

of stakeholders. To trigger collective

action IBAN ‘connects the dots’ between

the vast number of businesses, existing

initiatives, networks and stakeholders

around the world. On a global, regional

and national level, it facilitates access

to knowledge and information, enables

peerlearning and exchange formats and

fosters partnerships.

INCLUSIVE BUSINESS ACTION NETWORK (IBAN)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

With this report, IBAN commissioned three Ghanaian affordable housing experts, Sarfoh,

Kwadwo Ohene, Kavaarpuo, Godwin and Ayitio, Joseph to conduct a study on the current

stage of the sector.

EXPERTS

Experts on inclusive business and affordable housing contributed to this publication,

providing their feedback and also sharing their experience. We are particularly grateful to

Alfred Berkoh, Ellen Oteng-Nsiah, Tony Asare, Farouk Braimah and Maja Rotter.

CAHF Centre for Affordable Housing Finance

GAMA Greater Accra Metropolitan Area

GHL Ghana Home Loans Ltd

GHS Ghanaian Cedi

GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH

GLSS Ghana Living Standards Survey

GREDA Ghana Real Estate Developers’ Association

GSS Ghana Statistical Service

HC:Y Housing cost to income ratio

IBAN Inclusive Business Action Network

MWRWH Ministry of Water Resources, Works and Housing

NBFI Non-bank financial institution

PHC Population and Housing Census

R&D Research and development

SADA Savannah Accelerated Development Authority

SHC State Housing Corporation

SSNIT Social Security and National Insurance Trust

SUF Slum Upgrading Facility (UN-HABITAT)

TAMSUF Tema Ashaiman Municipal Slum Upgrading Facility

TCCU Tamale Cooperative Credit Union

THC Tema Housing Cooperative

UESP Urban Environmental Sanitation Project

UN-HABITAT United Nations Human Settlements Programme

USAID United States Agency for International Development

ABBREVIATIONS

BOX 1 Policy view on affordable housing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

BOX 2 Stakeholder views on affordable housing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

BOX 3 Key figures for Ghana . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

BOX 4 Making housing affordable . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

BOX 5 Methodologies for estimating housing stock . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

BOXES

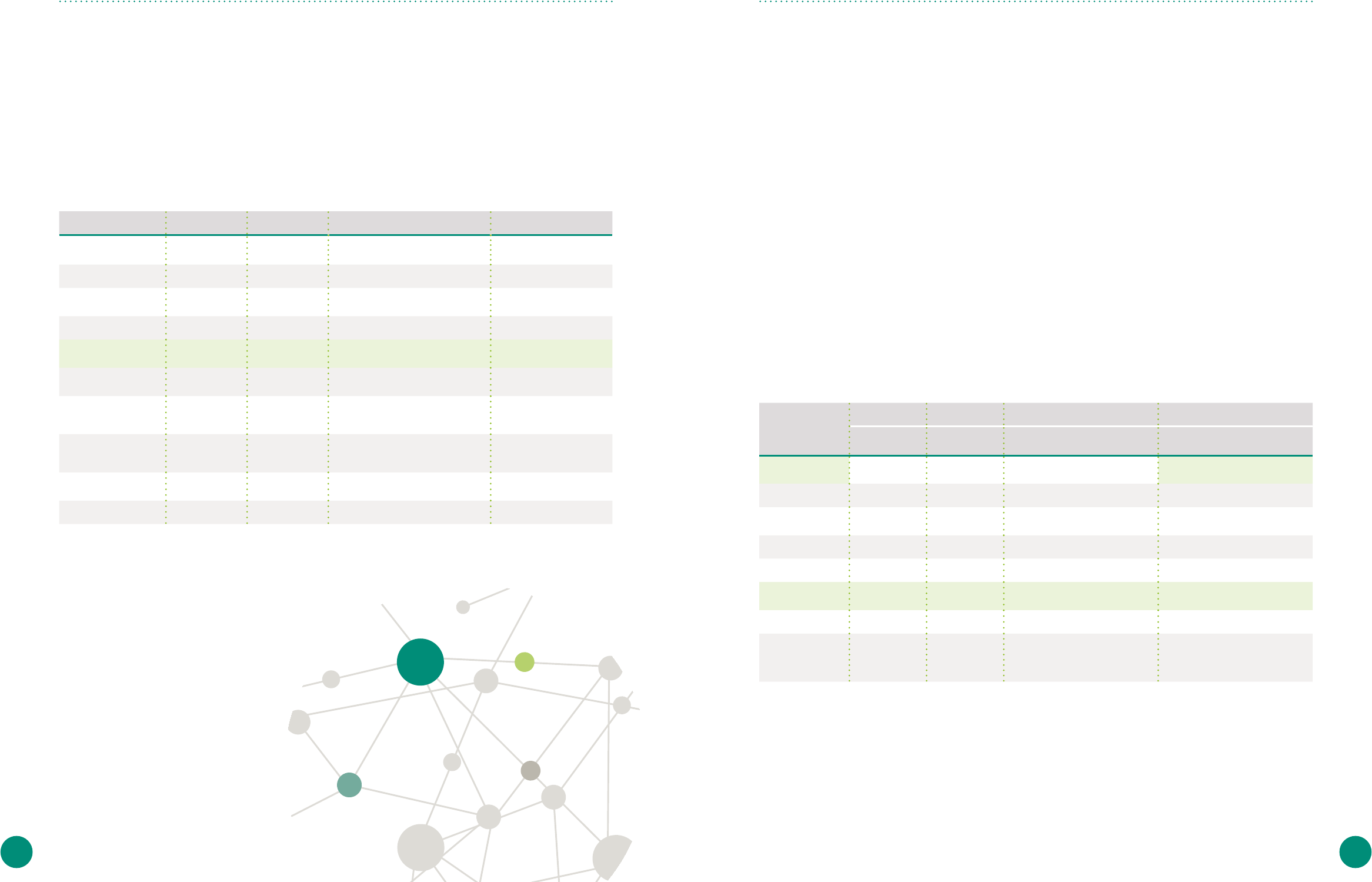

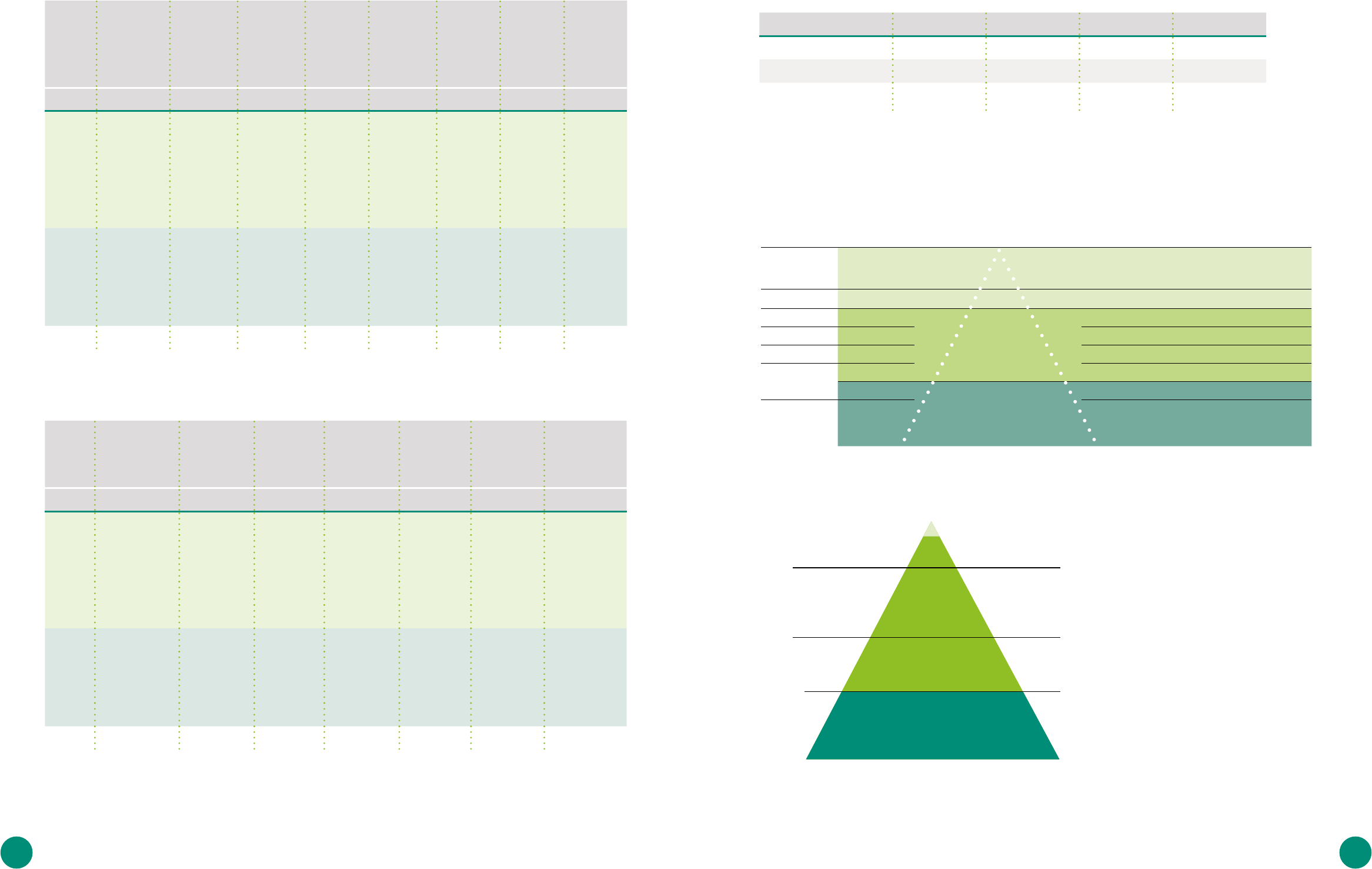

FIGURE 1 Percentage changes in demographics and housing stock . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12

FIGURE 2 Rooms occupied by households in urban and rural areas (2000 to 2010) . . . . .17

FIGURE 3 Housing affordability pyramid . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

FIGURE 4 Housing affordability in Ghana . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

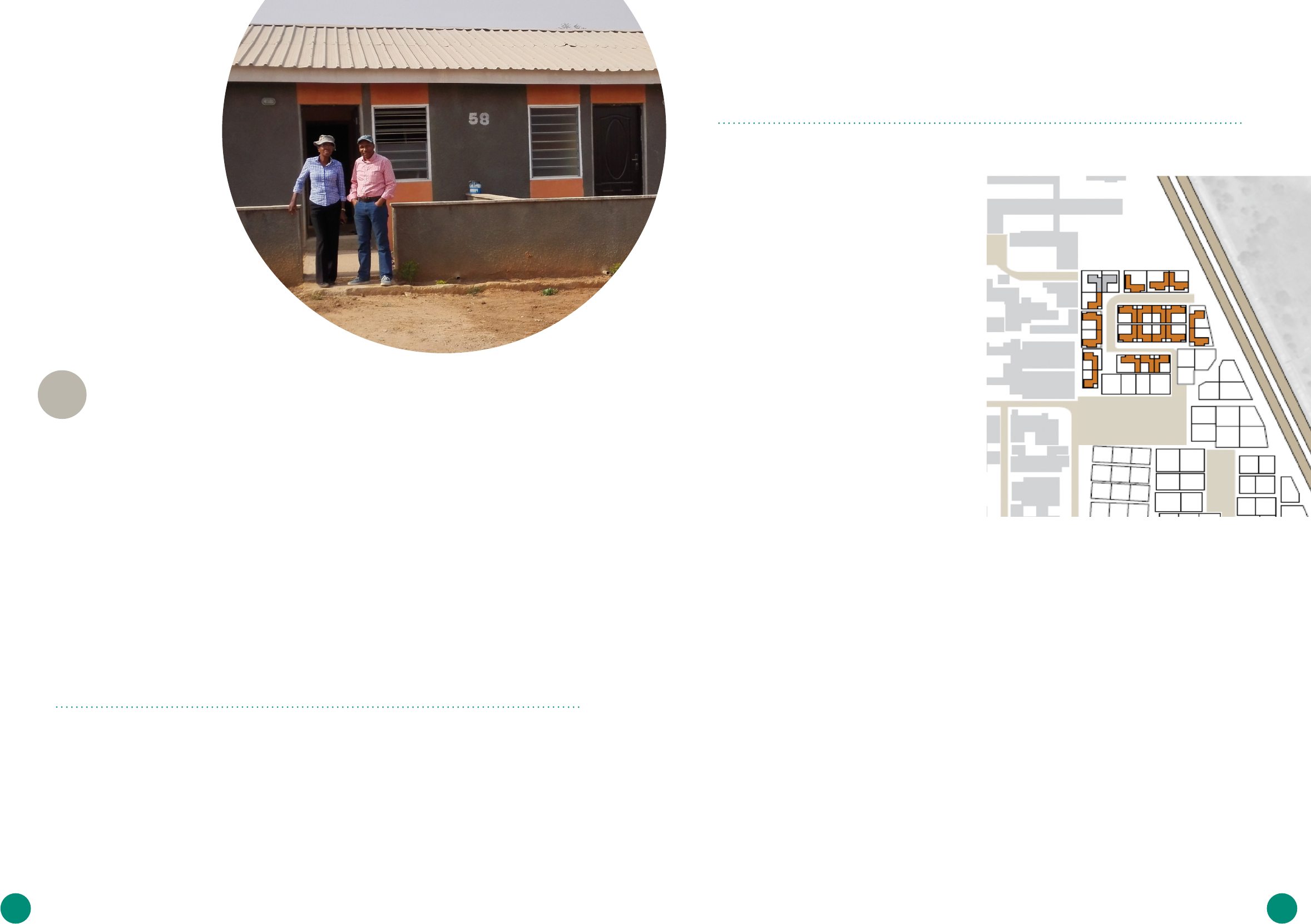

FIGURE 5 A two-bedroom terrace house. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

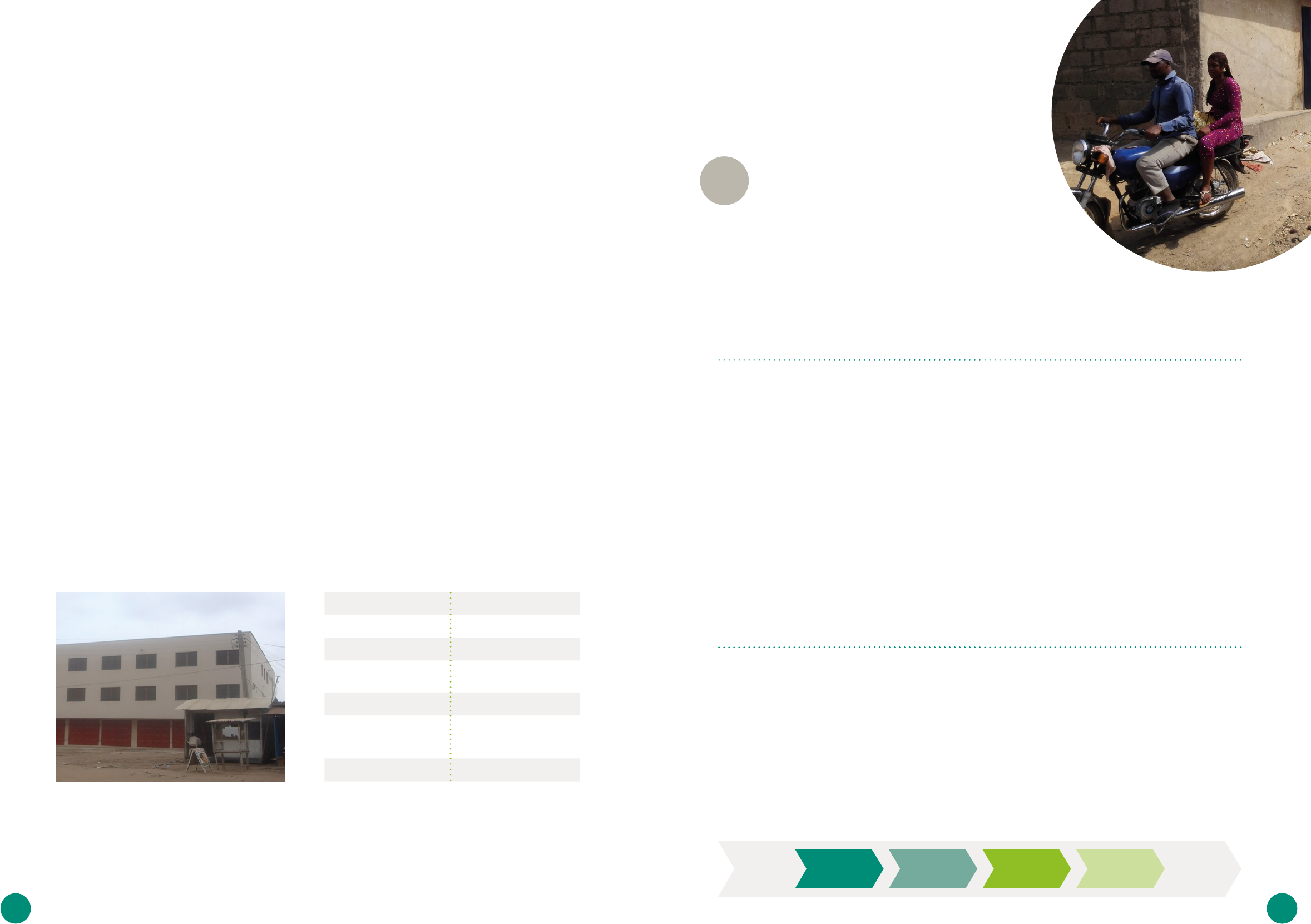

FIGURE 6 The housing value chain. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31

FIGURE 7 Cost components of a typical house built by the formal private sector. . . . . . 33

FIGURE 8 Identified housing sector stakeholders in Ghana . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .47

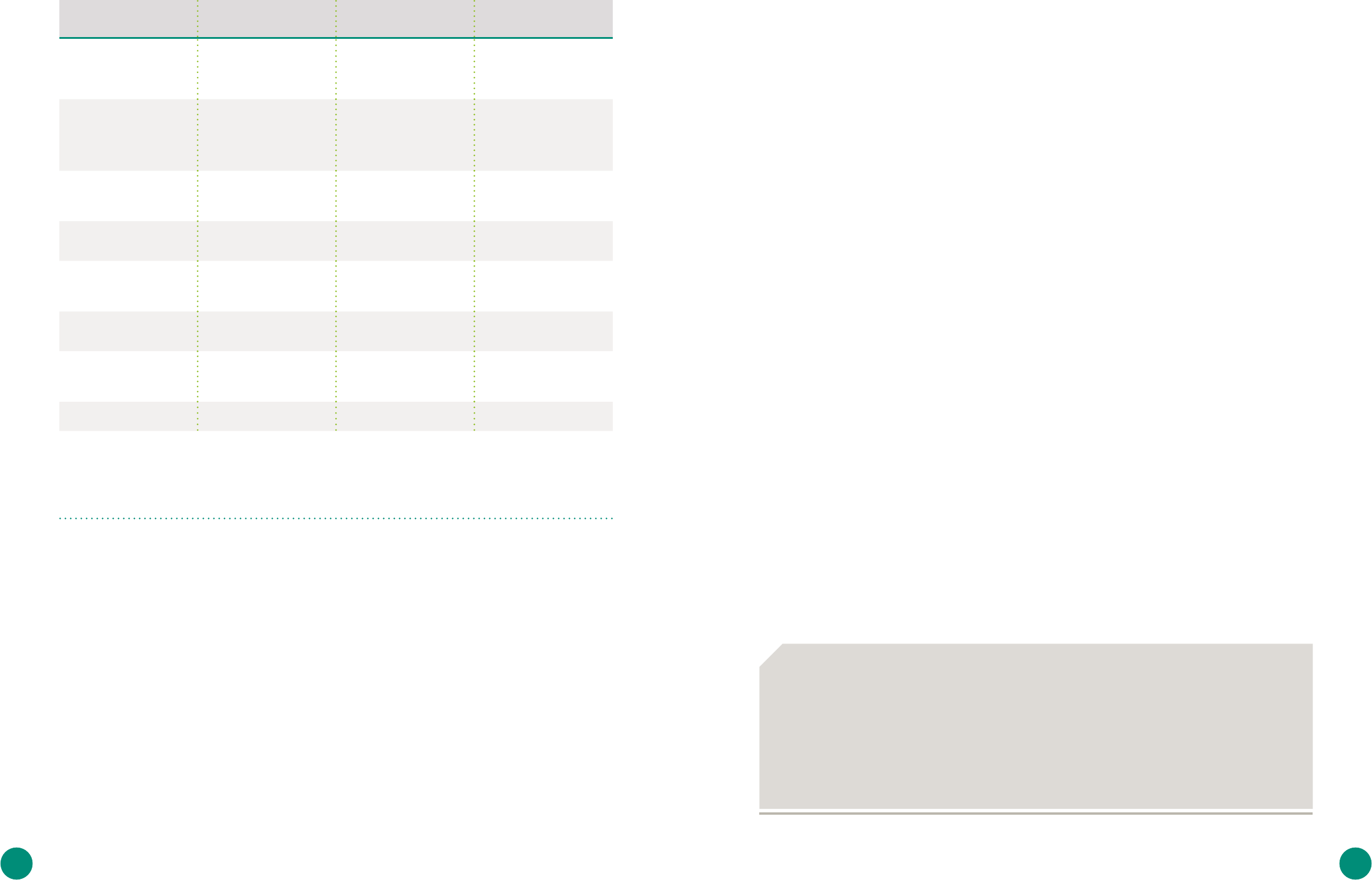

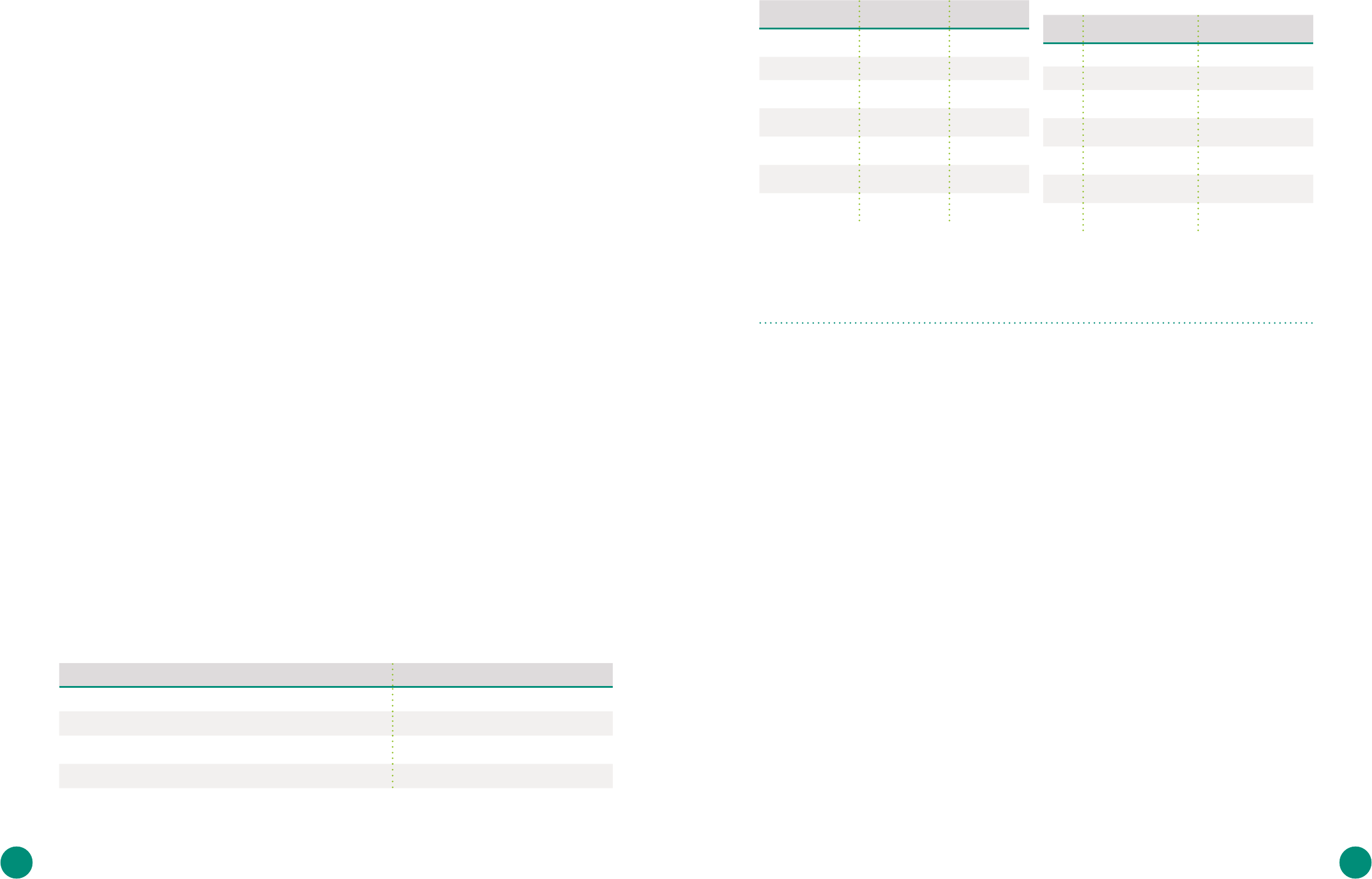

TABLE 1 Existing housing stock and households in 2010. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .13

TABLE 2 Trends in housing typology in Ghana. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

TABLE 3 Summary of the main materials used for external walling. . . . . . . . . . . . . .15

TABLE 4 Room occupancy in different localities. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

TABLE 5 Sleeping rooms per household in various localities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .17

TABLE 6 Housing tenure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

TABLE 7 Estimated housing need . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .19

TABLE 8 Analysis of housing need (2000 to 2025) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

TABLE 9 Value of the affordable housing market . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .21

TABLE 10 Housing expenditure by quintile group and type of locality. . . . . . . . . . . . 22

TABLE 11 Annual income and expenditure on rent. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

TABLE 12 Affordability determined using mean household income from GLSS 6,

indexed to 2016 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

TABLE 13 Matrix of business opportunities. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

TABLE 14 Top five sources of household loans in 2008 and 2014* . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

TABLE 15 Purposes for which loans were taken out . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

TABLE 16 Loan portfolio of the top four NBFIs in 2013 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

TABLE 17 The Ghanaian mortgage market in 2013. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

TABLE 18 Interest rates on mortgages of selected banks in 2013 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

TABLE 19 Institutional arrangement of the affordable housing sector . . . . . . . . . . . 48

TABLE 20 Summary of major government housing initiatives since Ghana's independence 52

TABLE 21 Changes in Ghana's demographics and housing stock (1960–2010) . . . . . . . 53

TABLE 22 Summary of key barriers/enablers for affordable and inclusive housing projects 54

FIGURES AND TABLES

76

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Access to decent and adequate housing is often considered as a basic human right.

However, low-income households face difficulties in accessing not only affordable

housing solutions but also housing of good quality. In Ghana both the informal and for-

mal sector supply of housing continues to be inadequate to meet the increasing demand.

This has resulted in acute and persistent housing deficits — a situation that presents a

complex mix of both challenges and opportunities. This report sets out the major issues

affecting affordable housing provision and seeks to present a business case for formal

private sector interventions in affordable housing in the country.

Housing conditions in Ghana

Housing supply is dominated by informal sector

operations with over 90% of the country’s housing

stock built incrementally by homeowners and

small-scale contractors which typically takes 5

to 15 years to complete. A significant proportion

of the houses built in this way are of a typology

known colloquially as compound houses. In urban

areas one in two households dwell in this kind of

communal housing type. Another significant ty-

pology is detached bungalow-type housing, which

in 2010 constituted 28.7% of the country’s total

housing stock.

There are notable differences with respect to the

building materials used across localities. In rural

areas, the building envelope of 55% of houses are

either mud or earth-based, whereas 85% of houses

in urban areas are sandcrete. Sandcrete is often

associated with modernity and there is a gradual

transition in the use to sandcrete based materials

as it is associated with modernity. As sandcrete

becomes more popular, local building materials

are being used less and less. This is problematic

because using local earth and clay building ma-

terials reduces housebuilding costs and reduces

post-construction costs on occupants given these

materials’ energy-saving properties.

In terms of house tenure, two in five households

in Accra, occupy rented accommodation while

some 27% of households live in rent-free arrange-

ments. In rural areas, three out of five households

own their dwellings. One-third of households in

both rural and urban areas occupy more than

two sleeping rooms while about 2.7 million urban

households occupy single-rooms. This situation

combined with the extent of rent-free occupancy

and the national average of 4.4 persons per house-

hold is indicative of serious overcrowding.

Affordable housing market and potentials

Housing affordability

Housing sold on the formal real estate market is

beyond the financial means of most households,

with only about 1% of households able to afford

the cheapest houses offered by formal developers.

For example, in 2015 the cheapest house cost USD

24,297. After paying the 20% deposit, the mortgagee

is required to make a monthly payment of USD 245

over a 20-year period and must have a monthly

income of USD 612 to quality. Meanwhile, monthly

income of households average USD 347.

Bank lending rates are standing at around 30% per

annum and thus housing finance is out of reach of

virtually all but those on high incomes households.

For example, average household incomes reported

in 2014 stood at GHS 16,644 (GSS 2014). Using the

housing cost-to-income metric, households able to

spend three times their annual incomes would be

able to afford accommodation worth USD 14,000.

Customer and value proposition

For the report, a limited survey of selected stake-

holders was carried out exploring what constitu-

tes ‘affordable’ housing. For private developers,

affordability is both a function of the quality of

the building fabric and the price relative to the

income of a target group. For financiers, it is linked

to a certain, arbitrarily-set price point related to

the cost of housing. For low-income households,

it is determined by price, build quality and loca-

tion. These different perspectives suggest that

affordability means different things to different

people. Affordability is thus seen differently by

different stakeholders depending on their function

along the housing value chain.

H

owever, this level of production only addres-

ses about 35% of the annual demand for new

housing (UN-HABITAT 2008). Given that the

recent boom in the real estate market distinctly

favours high-income households, which constitute

only 5% of the population, this deficit appears to

mainly affect the larger part of the housing market

that is persistently overlooked by market forces.

Previous approaches of successive governments to

directly provide housing have seldom achieved their

objectives. With both formal and informal housing

delivery inadequately meeting demand of all market

segments, the market presents both challenges and

opportunities particularly for low income housing

which is not addressed by the market.

This report presents the essential issues affecting

the provision of affordable housing in Ghana with

the aim of making a business case for the partici-

pation of multiple private and non-state actors and

interests in a more concerted fashion. Drawing on

Ghana’s 2015 National Housing Policy and on the

perspectives of key stakeholders representing diffe-

rent interests in the housing sector, the report pro-

vides a contextualised understanding of affordable

housing.

The report makes use of various estimations of the

housing demand situation and identifies the types

of affordable housing available on the market and

the financing mechanisms employed to deliver

lower-cost housing. Importantly, the report consi-

ders the segment of the housing sub-market that

can catalyse changes in the delivery of and access

to affordable housing. The report’s contents also

provided the background for dialogues at the three-

day workshop Affordable Housing in Ghana, held on

28–30 June 2016 and organised in partnership with

the World Bank. It is hoped that the contents of this

report prompt further discussions on this subject,

provide the ingredients to support sustainable inter-

ventions and introduce key players to the risks and

opportunities associated with the affordable housing

sub-market. Moreover, it is hoped that the combined

impact of the report and workshops fosters part-

nerships that result in the development of sustain-

able and scalable business solutions to address the

challenges of the affordable housing market.

Ghana’s real estate market is largely based on informal sector activities

1

— both for

supplying and allocating housing units. The housing market currently appears to be

experiencing significant investment and growth, arising from the country’s econo-

mic growth, oil discovery and exploration, and remittances. The numerous construc-

tion cranes visible over major cities like Accra, Tema and Kumasi serve to reinforce

this notion of a country on the up. Housing supply has undoubtedly enjoyed positi-

ve growth rates over the years. In 2008 supply was estimated at between 25,000 to

40,000 units per annum, representing a threefold increase on the previous decade.

Introduction

1

98

Qualitative research methods are useful for understanding the state of the housing

sector in Ghana. In qualitative inquiry, the aim is to explore a phenomenon in-depth,

which aligns with the objectives of this report. To better understand the dynamics of

affordable housing and propose practical recommendations, the authors purpose-

fully selected units of inquiry and data sources that allowed them us to learn from

and critically review housing interventions in the country. This involved undertaking

a desk study of secondary data – namely policies, programmes, projects, institutio-

nal frameworks, position papers and market reports on housing in Ghana. A list of

key literature on affordable housing in the country is provided in Appendix 1.

Research approach

2

T

he authors of the report, which is largely

based on the above-mentioned desk study,

drew on relevant literature to establish its

conceptual basis for affordable housing. This re-

view was supplemented with limited primary data

gathered from carefully selected stakeholders in

interviews that sought to further contextualise and

validate the conceptual basis established as well

as to generate inputs for the affordable housing

workshop. To develop understanding and thus

establish the framework for the formulation of

appropriate solutions, primary data respondents

were selected using parameters such as income

and socio-economic status, and education levels.

The profiles of these respondents are provided

later in this report. Participants in the primary data

collection exercise were sampled loosely

2

from

housing developers, mortgage financiers, public

policy experts and slum residents. In total, five

slum residents (one from each of the major slums

in Accra), one housing finance company represen-

tative, one formal private developer, one public

officer and two housing experts were interviewed

to augment the findings of the literature review.

A

ffordable housing is a concept that is

heavily influenced by the local context and

is therefore not easy to subject to global

norms. For some, its definition is a function of

household income and expenditure, benchmar-

ked not to exceed a ceiling relative to the overall

household income or expenditure, averaging 30%

(O’Dell, W. O., Smith M. and White D. 2004). However,

this varies between countries – for example, Cana-

da until the 1980s used a 25% household income

threshold (Hulchanski 2005). In India, a ceiling

of 40% is applied (Jones Lang LaSalle 2012), with

affordability measured according to the economic

status of a household. A variation of this definition

looks at how to make housing accessible to the

poor, who are defined as those with a household

income threshold of under USD 2 per day.

3

Others

define affordable housing as housing with costs

at or below a fixed price point, sometimes arbit-

rarily set, and deemed to be accessible to those

on lower incomes (Angel 2001). A variation on this

definition uses public subsidies as a factor for

determining what constitutes affordable housing

(which is defined in certain quarters as low-cost

housing that requires supply-side subsidies).

Elsewhere, affordable housing is broadly defined

as housing that is adequate in quality and location

and does not cost so much that it leaves its occu-

pants unable to meet their other basic living costs

or threatens their enjoyment of other basic human

rights (McBride et al. 2011). Here, other elements of

affordability come into play: quality, income, locati-

on, costs, and enjoyment of basic human rights. In

this regard, affordable housing is defined in some

cases to be housing of a specific size (determined

either by number of rooms or space) or of mini-

mum quality.

Box 2 below presents the differing views of what

constitutes affordable housing expressed by a

selection of interviewed stakeholders.

There are several different understandings of what constitutes affordable

housing, who is entitled to it and what role different stakeholders are required

to play in order to deliver housing and allocate it to beneficiaries. Box 1 below

contains the 2015 National Housing Policy’s definition of affordable housing.

Views on affordable housing

3

The ability of a household to spend up to thirty

percent (30%) of its gross annual income on

the rent or purchase price of housing where

the rent or purchase price includes applicable

taxes and insurances and utilities. When the

annual carrying cost of a home exceeds thirty

percent (30%) of household income, then it is

considered unaffordable for that household.

MWRWH 2015, p. V

NATIONAL POLICY PERSPECTIVET

Box 1 • POLICY VIEW ON AFFORDABLE HOUSING

Photo: peeterv/istockphoto.com

1110

A PRIVATE DEVELOPER’S VIEW

‘Affordability is relative and hence affordable

housing is decent accommodation, with at least

wet areas, that meets the target group’s needs.

The housing must have as a minimum a decent

toilet and bath and its cost must be relative to

the financial capacity of the target group.’

Managing director of a private propertydeveloper

A FINANCIER’S VIEW

‘An affordable house in Ghana is a house whose

cost ranges from GHS 100,000 to GHS 200,000,

taking into consideration people’s incomes and

the feasibility of the construction costs. A house

is only affordable because people have the

money to buy, or can access a mortgage to buy,

the property.’

Technical officer of a mortgage provider

Box 2 • STAKEHOLDER VIEWS ON AFFORDABLE HOUSING

In this report the definition of affordable housing

as ‘housing solutions which are priced or financed

in a way that enables low-income households … to

also be able to afford other basic needs’ (GIZ 2014,

p. 9) is used. The low-income households referred

to here are those that fall within the bottom two

income quintiles. Though used more loosely in

this report, the concept of affordability is linked

specifically with households occupying the base of

the economic pyramid — i.e. low-income earners.

4

In this case, housing solutions must be modelled

in relation to the purchasing power of prospective

owners or renters. This introduces flexibility into

the definition, as incomes and wages are often

location-specific. As such, a solution appropriate

for one area might not necessarily work in ano-

ther. Other locational issues; proximity to social

and civic services, economic opportunities and

social networks are critical in the decisions of low

income earners in choosing to reside in a particu-

lar neighbourhood. The element of basic needs is

equally important with regard to making housing

accessible. Houses should not be priced in a way

that compromises the resident households’ ability

to satisfy their other needs.

Research on affordable housing in Ghana is often

framed in terms of the public provision of af-

fordable housing and the mediatory role of state

institutions, with researchers considering whether

public policy would be able to alleviate the preca-

rious housing situation of the urban poor. With the

issues framed in these terms, the resulting studies

have tended to focus on the state’s attempts to

provide housing for low-income households, the

existing public financing options (Bank of Ghana

2006) and the influence of state policy in achieving

those aims. For instance, some scholars (Kona-

du-Agyeman 2001 and Sarfoh 2010) have examined

Ghana’s housing policy experience from the

pre-colonial era to contemporary Ghana, looking

at adopted policies and programmes in the light

of international discourse and the core–periphery

argument versus neoliberal and communitarian

approaches. Arku (2009) investigated the economic

logic of housing policies from 1929 to 1966 and

observed that colonial governments seldom acted

to provide housing for indigenous peoples except

occasionally for political and social motives. For

Sarfoh (2010), the direction of housing policy over

the years has been characterised by uncertainty

owing to (a) shifts in the orientation of governance

and the economic paradigms of global players and

(b) the strategic positioning of local actors as glo-

bal norms were reinterpreted. This uncertainty in

housing policy direction is epitomised by the coun-

try’s repeatedly unsuccessful efforts to develop a

comprehensive housing policy prior to 2015, when

a national housing policy was finally promulgated.

Others have considered the relationship between

who is building and what is being built in urban

Ghana (Tipple et al. 1998, and Korboe 1992). On the

question of who is building, Tipple et al. assert that

the motivation for house construction in urban

Ghana is to guarantee security of tenure. Other

studies, such as Karley and Akomea 2007 and

Obeng-Oddom 2011, examine the prospects and

challenges in the real estate sector. A key conside

-

ration in most of the existing studies is affordabi-

lity and the associated strategies for improving

access to affordable housing, albeit without a

clarification of the competing notions of this con-

cept (Boamah 2010). Awanyo (2009) draws attention

to the need to leverage already ubiquitous in-situ

building strategies, as a way of meeting housing

space demands among low-income earners. For

Tipple (1996) it is house extension that offers the

potential for affordable and sustainable housing.

In this approach, as a minimum the wet areas

(kitchen, bath and toilet) and at least one sleeping

area are completed for use, and options for later

expansion incorporated.

5

However, this kind of

piecemeal approach tends to lock up capital over a

considerable time.

Other studies mainly carried out by international

organisations attempt to provide a panoramic view

of the sector (e.g. CAHF, 2013; UN-Habitat, 2010;

UN-Habitat, 2011; World Bank, 2009; and UN-HAB-

ITAT, 2004). These present overviews of the housing

sector that examine the issues in aggregate

(covering land issues, finance, policy, institutional

aspects, housing needs and interventions, among

others) rather than focus on a particular sub-sec-

tor.

These studies do not look at the housing value

chain or the socially stratified lower-scale issues

of affordable housing in Ghana that are specific to

the poor. Neither do they explore the role of the

private sector in tackling these issues. Yet, given

the private sector’s understanding of the dynamics

of affordable housing provision, the housing mar-

ket and the mediatory roles of institutions, it has

a particularly crucial role to play in policy-making

and harmonious local economic development. It

is this gap that this report attempts to address by

providing a better understanding of the affordable

housing market.

28,5 MILLION

Population

54%

Urban population (% of total)

4,5%

Urbanisation rate (in 2014)

24.2%

Population under national poverty line

GHS 8

National daily minimum wage

21.4%

Proportion of employed population in informal sector

43.8%

Population living in slums

0.25

Mortgage to GDP ratio (in 2010)

70

Ease of doing business ranking (out of 189)

5

Number of procedures to register a property

46 DAYS

Time required to register property

1.10%

Cost, as a % of property value, of registering property

Box 3 • KEY FIGURES FOR GHANA

CAHF 2015, GSS 2014, UN-Habitat 2014, and Ministry of

Local Government and Rural Development 2013.

1312

Ghana’s 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) recorded the country’s

population as 24.6 million, of whom approximately half live in urban areas.

6

The

concentration is such that the primary cities of Kumasi, Sekondi-Takoradi and Ac-

cra, all of which are in the south of the country, hold more than 28% of the coun-

try’s population.

7

Furthermore, housing stock, the number of households and the

number of households per house all reflect this trend towards urbanisation.

Understanding Ghana’s

housing and demand

4

F

igure 1 shows that both the population and

the number of households increased bet-

ween 1960 to 2000. After the turn of the mill-

ennium, the rate of population growth witnessed a

decline while the number of households continued

to increase – albeit at a slower pace, which there-

fore suggests the beginnings of a decline by 2010.

The increasing formation of new households con-

forms with the shrinking household sizes observed

over the censual years. Household sizes peaked

in 2000 at 5.1 persons per household and subse-

quently declined to 4.4 persons per household in

2010. If this reduction in household size continues

without a corresponding significant slowdown in

population growth, and unless the current pace

of housebuilding is ramped up, the demand for

housing will remain high.

The housing situation differs greatly between the

regions in the north of the country and those in

the south, which perhaps reflects the development

gap existing between these two zones. Northern

regions have higher household sizes and less

housing stock compared to southern regions. Si-

milarly, there are more multifamily living arrange-

ments in the south than in the north of the coun-

try (with the exception of the Upper East region),

the south having about 50% more households per

house (see Table 1 below).

REGION

NUMBER OF

HOUSES

NUMBER OF

HOUSEHOLDS

RURAL SHARE

OF HOUSING

STOCK

HOUSEHOLDS

PER HOUSE

AVERAGE

HOUSEHOLD

SIZE

ALL REGIONS

3,392,745 5,467,136 57.7 1.6 4.4

ASHANTI

574,066 1,126,216 53.0 2.0 4.1

GREATER ACCRA

474,621 1,036,426 13.0 2.2 3.8

EASTERN

431,697 632,048 64.1 1.5 4.1

VOLTA

399,953 495,603 72.2 1.2 4.2

WESTERN

380,104 553,635 67.5 1.5 4.2

CENTRAL

346,699 526,764 61.8 1.5 4.0

BRONG-AHAFO

331,967 490,519 63.4 1.5 4.6

NORTHERN

257,311 318,119 71.3 1.2 7.7

UPPER EAST

114,034 177,631 79.2 1.6 5.8

UPPER WEST

82,293 110,175 85.4 1.3 6.2

Table 1 • EXISTING HOUSING STOCK AND HOUSEHOLDS IN 2010

Figure 1 • PERCENTAGE CHANGES IN DEMOGRAPHICS AND HOUSING STOCK

GSS 2014.

8

%

20

30

40

50

10

0

60

70

80

90

Increase in households

Population growth rate

Increase in population

Increase in housinng stock

1960-70 1970-84 1984-2000 2000-2010

Photo: VanWyckExpress/istockphoto.com

1514

T

he most common housing typology found

throughout Ghana is the compound house,

which accommodates multiple households

in a shared building. The data from the population

and housing censuses (2000 and 2010) and the

Ghana Living Standards Surveys (GLSS) (2008 and

2014)

9

show that, compared to the other housing

typologies, the share of compound housing in-

creased from 50% to nearly 70% between 2000 and

2010 (see Table 2 in which compound housing is

highlighted). This finding calls into question the

generally held notion that households, and parti-

cularly those in urban locations, prefer detached

bungalows. On the contrary, it would seem that

people’s housing preferences are flexible when it

comes to the country’s housing stock. This trend

in sharing housing arrangements applies to both

urban and rural areas.

I

n general, the types of materials used to build

houses can help in determining whether the

properties potentially fall into the affordable

housing category. This category applies to housing

built with materials that fall below the minimum

standards stipulated in the national building re-

gulations (LI 1630) and are thus unable to protect

inhabitants from a range of hazards such as harsh

weather conditions. The building regulations deem

housing walls constructed with ‘temporary ma-

terials’ such as metal sheets, wood, thatch and

palm leaves to be sub-standard. Often, this kind of

housing is occupied by people on low incomes.

Table 3 below provides an overview of housing in

Ghana based on the types of building materials

used. However, this is not a strong measure as it

does not give any idea of the present condition of

the properties.

In rural areas, where 73% of rural households live

in dwellings built mainly with mud, housing issues

centre more on questions of quality rather than

quantity (GSS 2008). In contrast, the use of sand-

crete is more common in urban areas (see table 3

in which this highlighted in yellow). Even though

this is a singular proxy indication of housing qua-

lity, it reflects expenditure patterns on housing, as

urban dwellers spend on average 118% more on

housing than their rural counterparts. However, this

is not to insinuate that issues of housing quality

are specific to rural areas. On the contrary, 42.8% of

urban dwellers live in slums (UN-HABITAT, 2014).

Although landcrete, burnt bricks and bamboo are

proven building materials and their source materi-

als are readily available locally, their use is mainly

confined to wall building in both rural and urban zo-

nes. Sandcrete and concrete walling dominates the

urban landscape whereas earthen material walling

is commonest in rural areas. A transition away from

earthen materials towards concrete and sandcrete

use has, however, been observed in rural areas.

TRENDS IN TYPES OF HOUSING (2000 TO 2014) HOUSING MATERIALS (EXTERNAL WALLING)

ACCRA (GAMA) OTHER URBAN ALL URBAN ALL RURAL

TYPE OF

DWELLING

GLSS 5

2008

GLSS 6

2014

GLSS 5

2008

GLSS 6

2014

PHC

2000

GLSS 5

2008

PHC

2010

GLSS 6

2014

GLSS 5 PHC

2010

GLSS 6

2014

SEPARATE HOUSE

8,5 14,9 4,8 14,1 16,0 6,0 19,3 14,3 2,4 40,1 16,4

SEMI-DETACHED

HOUSE

6,8 6,4 3,4 5,9 14,9 4,5 7,8 6,1 2,7 6,3 8,2

FLAT/APARTMENT

8,9 7,4 4,5 4,6 7,2 5,9 7,0 5,5 0,8 1,9 1,3

COMPOUND HOUSE

(ROOMS)

53,9 63,9 55,5 70,0 51,6 55,0 58,7 68,1 35,1 42,9 51,3

SEVERAL HUTS/

BUILDINGS

2,6 0,7 2,9 4,0 2,5 2,7 1,0 3,0 9,5 5,7 21,7

TENTS/IMPROVISED

HOME (KIOSK,

CONTAINER, ETC.)

2,3 3,7 0,1 0,4 0,1 0,8 0,3 1,5 0,2 0,2 0,1

LIVING QUARTERS

ATTACHED TO

OFFICE/SHOP

— 0,6 — 0,2 0,6 — — 0,3 — — 0,2

UNCOMPLETED

BUILDING

— 2,4 — 0,6 4,3 — 2,1 1,2 — 1,0 0,2

OTHERS

1,4 0,1 0,1 0,2 4,3 0,5 — 0,2 0,2 — 0,7

Source: compiled using data from GSS (2000, 2008, 2010 and 2014).

Table 2 • TRENDS IN HOUSING TYPOLOGY IN GHANA

MAIN MATERIALS

USED FOR EXTER-

NAL WALLING

10

ACCRA (GAMA) OTHER URBAN ALL URBAN ALL RURAL

GLSS 5

2008

GLSS 6

2014

GLSS 5

2008

GLSS 6

2014

PHC

2000

GLSS 5

2008

PHC

2010

GLSS 6

2014

PHC

2000

GLSS 5

2008

PHC

2010

GLSS 6

2014

MUD/MUD

BRICKS/EARTH

2,3 0,6 26,5 15,0 21,5 18,5 12,4 10,4 74,5 72,9 60,5 56,9

WOOD

7,5 6,5 0,5 0,6 5,4 2,8 4,8 2,5 2,7 1,0 1,8 0,7

METAL/SHEET/

SLATE/ASBESTOS

0,5 1,0 0,1 1,0 0,9 0,2 1,0 1,0 0,3 0,1 0,5 0,5

STONE

0,2 0,2 0,5 - 0,3 0,4 0,2 0,1 0,2 0,3 0,2 0,1

BURNT BRICKS

0,3 0,1 0,8 0,4 2,0 0,6 0,7 0,3 1,1 0,6 0,6 1,3

CEMENT BLOCKS/

CONCRETE

88,4 91,5 69,4 82,5 65,3 75,7 78,5 85,3 16,6 21,8 32,1 39,7

LANDCRETE

— — — 0,4 2,9 — 1,2 0,3 2,6 3,1 2,5 0,3

BAMBOO/PALM

LEAVES/THATCH

(GRASS/RAFFIA/

OTHERS)

— 0,1 — 0,1 1,6 — 1,3 0,1 2,0 0,1 1,7 0,5

Source: compiled using data from GSS (2000, 2008, 2010 and 2014).

Table 3 • SUMMARY OF THE MAIN MATERIALS USED FOR EXTERNAL WALLING

1716

T

he level of overcrowding in Ghana’s

housing, both in urban and rural areas, is

increasingly becoming a concern. Half of

the country’s total number of households dwell

in single rooms, making single-room occupancy

the commonest occupancy type, and over 75% of

households occupy either one or two rooms (see

the green-shaded rows in Tables 4 and 5). Given

the average household size in Ghana stands at 4.4

persons, it can be inferred that single- and dou-

ble-room dwellings suffer moderate to significant

levels of overcrowding.

The situation is more acute when one considers

occupancy in terms of sleeping rooms. The 2010

PHC acknowledges differences between room

occupancy per household and sleeping-room

occupancy per household, with the latter recording

much higher figures. Some households have two

or more rooms but only use one for sleeping. The

second room usually serves as the living room

and/or kitchen.

The analysis of the number of rooms occupied

compared to the size of the household reflects the

increasing pressure on the existing housing stock.

HOUSING TYPES BY OCCUPANCY

PROPORTION

OF ROOMS

OCCUPIED PER

HOUSEHOLD

ACCRA (GAMA) OTHER URBAN ALL URBAN ALL RURAL

PHC

2000

GLSS 5

2008

GLSS 6

2014

GLSS 5

2008

GLSS 6

2014

PHC

2000

GLSS 5

2008

PHC

2010

GLSS 6

2014

PHC

2000

GLSS 5

2008

PHC

2010

GLSS 6

2014

ONE ROOM

45,2 53,6 42,7 60,6 58,5 47,5 58,3 51,4 53,5 29,5 51,9 35,9 49,9

TWO ROOMS

33,2 30,8 35,4 22,8 22,4 24,0 25,5 24,6 26,5 23,7 26,2 25,1 26,7

THREE ROOMS

6,7 8,3 9,0 8,7 9,1 8,9 8,6 9,1 9,1 15,4 12,5 14,7 10,7

FOUR ROOMS

5,5 3,0 6,4 4,3 5,0 6,0 3,8 5,6 5,5 9,9 4,7 9,0 6,1

FIVE ROOMS

4,0 4,3 6,5 3,6 5,0 4,3 3,8 3,3 5,5 6,7 4,7 5,6 6,6

SIX ROOMS

1,9 4,3 6,5 3,6 5,0 2,7 3,8 2,2 5,5 4,6 4,7 3,3 6,6

SEVEN ROOMS

1,1 4,3 6,5 3,6 5,0 1,7 3,8 1,4 5,5 3,0 4,7 2,2 6,6

EIGHT ROOMS

0,8 4,3 6,5 3,6 5,0 1,3 3,8 0,8 5,5 2,2 4,7 1,6 6,6

NINE OR MORE

ROOMS

1,6 4,3 6,5 3,6 5,0 3,6 3,8 1,4 5,5 5,0 4,7 0,9 6,6

Source: compiled using data from GSS (2000, 2008, 2010 and 2014).

Table 4 • ROOM OCCUPANCY IN DIFFERENT LOCALITIES

PROPORTION OF

SLEEPING ROOMS

OCCUPIED PER

HOUSEHOLD

11

URBAN RURAL

PHC 2000 PHC 2010 PHC 2000 PHC 2010

ONE ROOM

61,9 61,4 39,1 45,5

TWO ROOMS

17,5 22,2 25 26,9

THREE ROOMS

7,6 7,8 14,5 13,1

FOUR ROOMS

4,6 4,2 8,3 6,8

FIVE ROOMS

2,6 2 4,6 3,2

SIX ROOMS

1,7 1,1 3,1 1,9

SEVEN ROOMS

1 0,5 1,8 0,9

EIGHT ROOMS

0,8 0,6 1,2 0,6

NINE OR MORE

ROOMS

2,3 0 2,4 1

Source: compiled using data from GSS (2000 and 2010).

Table 5 • SLEEPING ROOMS PER HOUSEHOLD IN VARIOUS LOCALITIES

Source: produced by the authors using data from GSS (2008 and 2014).

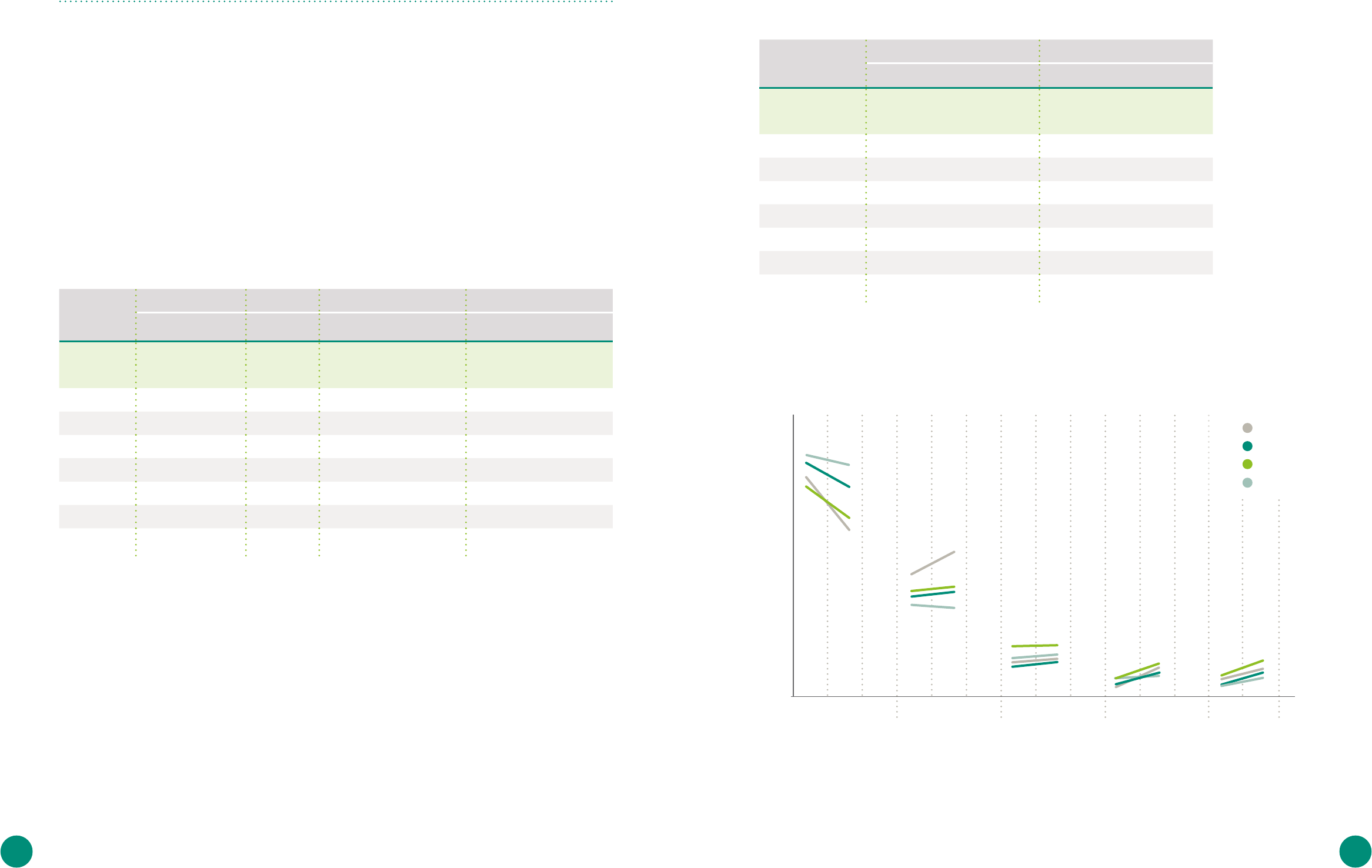

Figure 2 • ROOMS OCCUPIED BY HOUSEHOLDS IN URBAN AND RURAL AREAS 2008 TO 2014

%

10

20

30

40

50

60

0

70

All rural

Other urban

All urban

GAMA

2008-2014

1 ROOM 2 ROOMS 3 ROOMS 4 ROOMS 5+ ROOMS

2008-2014 2008-2014 2008-2014 2008-2014

1918

T

he overview of housing tenure in Ghana is

quite revealing, with urban and rural areas

displaying marked differences. Whereas

two-thirds of households own their homes in rural

areas, only a third do in urban areas. Urban areas

have more renters (one-third) than rural areas

(one-tenth). A third tenure type, not uncommon in

Ghanaian society, is rent-free status, which cons-

titutes around a quarter of households’ tenure in

both urban and rural areas. The share of housing

owned by relatives (33%) relates strongly with the

proportion of households with rent-free tenure

(27%). The higher ratio of rural households living in

dwellings owed by relatives (60%) reflects the ‘fa-

mily housing’ context whereby the extended family

is able to secure a cohabitation arrangement on

the basis of filial relationships and family patriar-

chal ties.

It is reasonable to assume that a large segment

of the households in need of affordable housing

interventions are those that are presently in rent-

free accommodation or are perching or squatting.

On the basis of this assumption, it is possible to

deduce that in 2010, 27% of households required

affordable housing solutions.

HOUSING TENURE

HOUSING

UNITS BY

TENURE TYPE

AND LOCALITY

ACCRA (GAMA) OTHER URBAN ALL URBAN ALL RURAL

PHC

2000

GLSS 5

2008

GLSS 6

2014

PHC

2000

GLSS 5

2008

GLSS 6

2014

PHC

2000

GLSS 5

2008

PHC

2010

GLSS 6

2014

PHC

2000

GLSS 5

2008

PHC

2010

GLSS 6

2014

OWNING

38.2 26.6 35.2 41.4 25.8 31.7 41.4 26.1 32.7 32.8 71.7 58.7 65.5 62.1

RENTING

40.7 45.9 41.0 35.8 38.5 39.3 35.8 40.9 45.0 39.9 9.9 9.1 13.5 10.7

RENT-FREE

19.9 24.8 23.1 21.6 35.1 28.6 21.6 31.7 21.2 26.8 17.6 32.0 20.3 27.0

PERCHING

12

1.2 2.7 0.5 1.2 0.6 0.2 1.2 1.3 0.5 0.3 0.8 0.3 0.4 0.2

SQUATTING

— — 0.3 — — 0.2 — — 0.4 0.2 — — 0.1 0.1

Source: compiled using data from GSS (2008 and 2014).

Table 6 • HOUSING TENURE

E

stimates of the housing deficit in Ghana vary

widely, due in part to confusion arising from

what defines and how to distinguish between

a house and a dwelling unit. Another factor is the

difficulty in determining the quantity of housing

supplied through informally self-managed pro-

cesses. The data in Table 7 below exemplifies this

uncertainty regarding overall housing needs and

unmet demand.

ESTIMATED MARKET VOLUME FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING

IN GHANA

Source: compiled using data from the UN-HABITAT (2011), the Ministry

of Water Resources, Works and Housing (2015) and GSS (2005).

SOURCE TOTAL HOUSING STOCK ANNUAL SUPPLY DEFICIT/NEED ANNUAL NEED

GOVERNMENT OF

GHANA (1987)

— — — 101,800

13

AMOA-MENSAH (2003)

— 37,000 — 90,000

UN-HABITAT (2004)

2,181,975 — — 1,010,000 by 2010

GHANA STATISTICAL

SERVICE (2005)

2,181,797 — —

138,085 units per annum;

3,500,000 by 2025

MAHAMA AND ANTWI

(2006)

— 25,000

300,000,

1,200,000 by 2005

130,000

ASIAMAH (2006)

— — 800,000 —

BANK OF GHANA (2007)

2,181,975 —

1,500,000 in 2000 with an

additional 665,000 by 2010

—

KARLEY (2008)

2,200,000 25,000–40,000 500,000 70,000

UN-HABITAT (2010)

— 250,000 — 133,000

GOVERNMENT OF

GHANA (2015)

3,392,745 —

4,000,000 rooms between

2000 and 2010; 5,700,000

rooms by 2020.

—

Table 7 • ESTIMATED HOUSING NEED

2120

What is clear is that housing supply has fallen far

behind housing needs over the years. The esti-

mated current annual deficit ranges from 106,806

to 170,751 units.

14

Assuming the upper estimates

hold true, the country will have an aggregate

deficit of 7.2 million rooms by 2020 (MWRWH 2015).

A substantial proportion of this deficit will be in

affordable housing, which is needed in some cases

to reduce crowding – due to rent-free status or

less than adequate dwellings – and in others to

replace dilapidated buildings.

Another way of estimating the affordable housing

market is to extrapolate from expenditure on

housing

15

, assuming that those in the lowest two

income quintiles are in need of affordable housing.

Table 9 shows that there has been substantial

growth in housing expenditure, although a large

gap exists between urban and rural households:

of the total of GHS 814 million spent on housing

in 2008, GHS 575 million was spent in urban areas

and about half of that was spent in rural areas. By

2014 the total spend on housing had grown to GHS

5.997 billion, of which GHS 4.6 billion was spent in

urban areas. As such, spending on housing in rural

areas was only one third of that in urban areas.

Housing expenditure as a share of total household

expenditure grew threefold between 2008 and

2014, with housing now constituting 11% of house-

hold expenditure for the lowest two quintiles and

rising marginally to 13% for the highest income

quintile.

Using the proportion of expenditure spent on

housing to calculate how much potential income is

available to those investing in affordable housing

provides a total figure of GHS 1.2 billion, an equiva-

lent of USD 536 million (as at 31 December 2013).

The estimate includes spending on housing con-

struction, the extension of existing buildings, and

rent, maintenance and utility payments. It excludes

outgoings for furnishings, fixtures and fittings, and

other consumables associated with the occupation

of the housing. Considered together, the estimated

existing housing deficit and level of expenditure on

housing serve to highlight the huge and untapped

opportunities awaiting the private sector.

Even though there has been a boom in housing

construction, investments have mainly targeted

high-income, low-risk borrowers. The amount of

investment is significant, with mortgages worth a

total of USD 180 million taken out as at 2013 (Adu

2014). However, the impact of these new-builds on

the overall housing stock has not been as signifi-

cant as the combined output of individual midd-

le- to low-income households whose incremental

approaches to building have dominated total

housing supply (Boamah 2014).

Based on the average household incomes reported

in the GLSS 6 (indexed to 2016), households can

afford USD 14,000 at house cost: income(HC:Y) ratio

of 3. If they can manage to spend more on housing,

at an HC:Y of 5, they could reach up to USD 23,000.

Table 12 shows that, in rural areas, households can

afford to spend USD 9,000 at an HC:Y of 3 on either

renting or purchasing housing. Rising inflation and

the persistently falling value of the Ghanaian Cedi

(GHS) reduce how much households are able to

spend on housing.

Item Figures

Total number of households

6,601,500

Households forming quintiles 1 and 2

2,640,600

Annual household expenditure by those in quintile 1

GHS 347.7

Annual household expenditure by those in quintile 2

GHS530

Proportion of housing expenditure for quintiles 1 and 2 in 2014

19.5%

Total amount spent by quintiles 1 and 2 on housing

GHS 1,158,827,310

Source: compiled using data from the GSS (2014).

Table 9 • VALUE OF THE AFFORDABLE HOUSING MARKET

Source: GSS (2005), and Population Data Analysis Reports, Vol. 2, p. 58, Table 1.57.

PROJECTED

INDICATORS

2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 INCREASE

TOTAL POPULATION

18,912,079 21,134,500

23,458,808

(24,658,823)

25,950,150 28,511,828 31,311,432 —

HOUSEHOLD POPULA-

TION (98.7% OF TOTAL

POPULATION)

18,666,222 20,859,752 23,153,843 25,612,798 28,141,174 30,904,383 —

ASSUMED HOUSE-

HOLD SIZE

5.1 5.2

5.2

(4.4)

5.2 5.2 5.2 —

PROJECTED HOUSING

NEED

3,660,044 4,011,491 4,452,662 4,925,538 5,411,764 5,943,151 —

ACTUAL HOUSES

NEEDED (1.7 HOUSE-

HOLDS/ HOUSE)

2,152,967 2,359,700 2,619,213 2,897,375 3,183,390 3,459,971 —

INCREASED NEW

HOUSING NEED

— 206,733 259,513 278,162 286,015 312,581 1,343,004

DILAPIDATED HOUSES

— 327,296 353,955 392,882 492,554 541,176 2,107,863

TOTAL ADDITIONAL

HOUSING NEEDED

— 534,029 613,468 671,044 778,569 853,757 3,450,867

PERCENT INCREASE

— 24.8 26.0 25.6 26.9 26.8 60.3

Table 8 • ANALYSIS OF HOUSING NEED 2000 TO 2025

2322

AFFORDABILITY IN USD

18

GAMA OTHER URBAN ALL URBAN ALL RURAL

AT HC:Y RATIO OF 3

13,672.23 18,252.52 16,809.52 9,162.10

AT HC:Y RATIO OF 4

18,229.64 24,336.69 22,412.70 12,216.13

AT HC:Y RATIO OF 5

22,787.05 30,420.86 28,015.87 15,270.17

Source: compiled using data from UN-HABITAT (2011).

Table 12 • AFFORDABILITY DETERMINED USING MEAN HOUSEHOLD

INCOME IDENTIFIED IN GLSS 6, INDEXED TO 2016

Source: UN-HABITAT, 2011

19

.

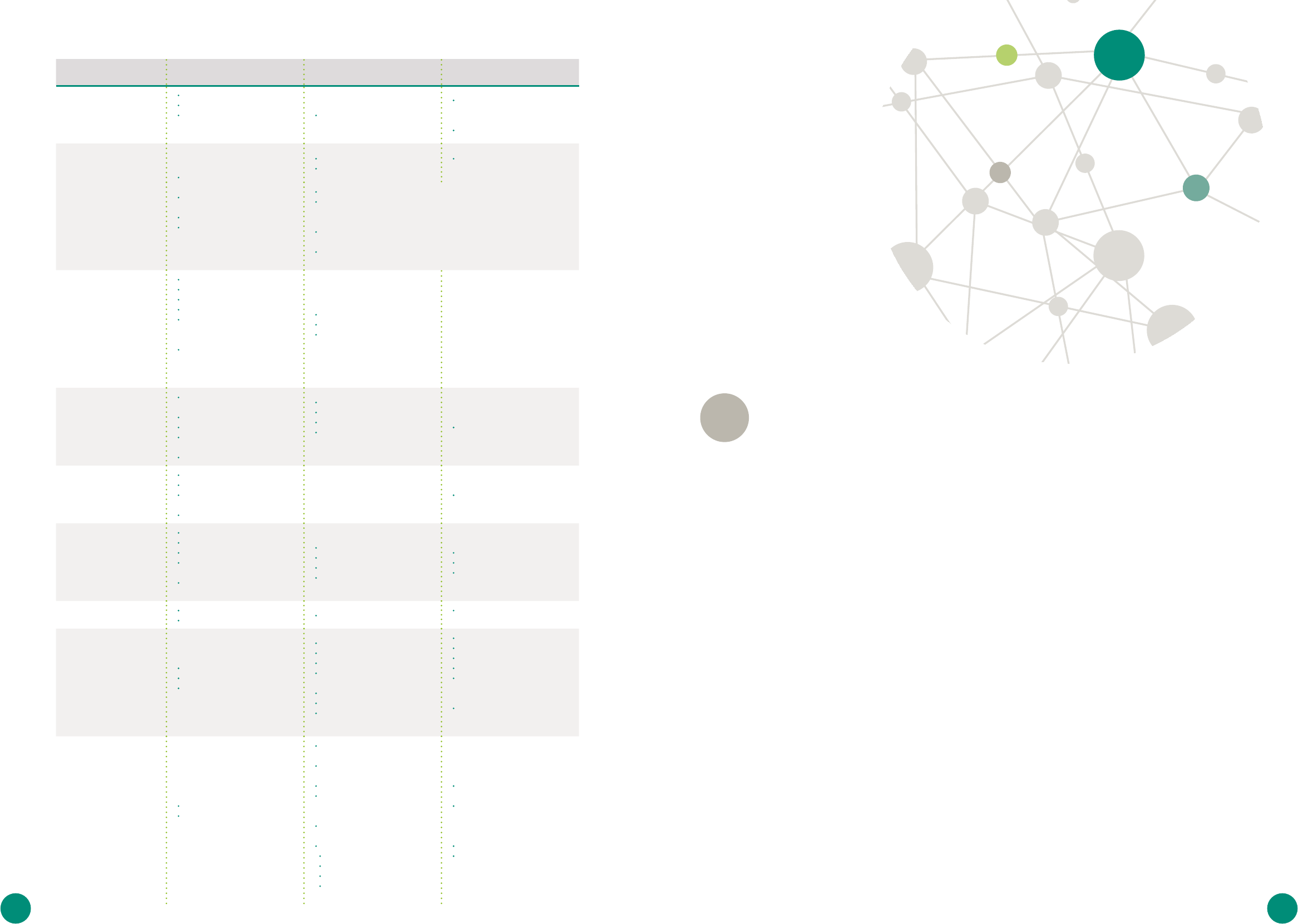

Figure 3 • HOUSING AFFORDABILITY PYRAMID

Income

Range

Income

GHC/month

Percentage of all

Households

Maximum

affordability

(in GHC) assu-

mining 3 times

annual income

Housing cost

(GHC) aimed at

the thresholds

Monthly

maximum rent

levels (GHC)

affordable at

R:Y of 10%

Very High >4,000

5%

180,000 476,000 &

204,000

500 +

High 3,001–4,000

10%

144,000 163,200 400

Mid-high 2,001–3,000

50%

of households

can afford housing

costing between

GHC12,001 and GHC72,000

108,000 95,200 300

Middle 1001–2,000 72,000 Up to 54,000 200

Moderate 501–1,000 36,000 100

Low income 101–500 18,000 50

51–100

35%

of households can

afford housing costing

GHC12,000 or less

12,000 10

No wage

income

0–50

Source: CAHF 2013.

Figure 4 • HOUSING AFFORDABILITY IN GHANA

The cheapest newly built house for sale is

$25 000. A buyer would have to put down

a $2500 deposit and earn $970/month to

afford a 20 year mortgage (US dollar deno-

minated) at 13,5%.

About 90% og Ghana's housing stock has

been produced through self-build. A sizeab-

le middel class suggests opportunities for

microfinance. These are being explored by

Habitat for Humanity International with its

MicroBuild Fund.

$1,25/day

Ghana is 52,52% urban

INTERNATIONAL POVERTY LINE

51,8%

live on less than

$60/month

$2/day

$4/day

Source: compiled using data from GSS (2008 and 2014)

16

Quintile/

locality

Mean annual

household

expenditure

(GHS)

Mean annual

per-capita

expenditure

(GHS)

Percentage

shares

Percentage

of expen-

diture on

housing (%)

Mean annual

household

cash ex-

penditure

on housing,

water, electri-

city and gas

(GHS)

Mean annual

per-capita

cash expen-

diture on

housing,

water, elec-

tricity and

gas (GHS)

Total an-

nual cash

expenditure

on housing,

water, elec-

tricity and

gas (million

GHS)

Mean

household

size

Year

2008 2014 2008 2014 2008 2014 2008 2014 2008 2014 2008 2014 2008 2014 2008 2014

Lowest

821 3,924 132 664 7.1 5.6 3.4 10.9 12 — — 57 — — 6.4 6.1

Second

1,242 5,833 247 1,194 10.8 10.0 2.6 10.9 23 — — 106 — — 5.1 5.0

Third

1,500 7,444 367 1,761 14.7 14.6 2.5 11.5 36 — — 178 — — 4.4 4.4

Fourth

1,942 9,238 548 2,656 21.0 21.9 2.5 12.0 60 — — 276 — — 3.7 3.6

Highest

2,864 14,665 1,261 6,337 46.3 47.9 2.2 13.3 136 — — 709 — — 2.5 2.6

Accra

3,009 13,677 — 5,039 — 25.8 4.5 16.7 — — — — — — 3.3 3.4

Other

urban

2,170 9,841 — 3,407 — 39.9 2.2 12.6 — — — — — — 3.6 3.7

Urban

2,449 11,061 — 3,926 — 65.8 3.2 14.2 325 1,288 115 463 575 4,638 3.5 3.6

Rural

1,514 7,152 — 2,112 — 34.2 1.5 9.0 128 589 38 184 239 1,359 4.4 4.5

Ghana

1,918 9,317 644 3,117 100.0 100.0 — 12.4 212 1,015 71 354 814 5,997 4.0 4.0

Table 10 • HOUSING EXPENDITURE BY QUINTILE GROUP AND TYPE OF LOCALITY

Source: compiled using data from GSS (2008 and 2014)

17

Quintile Average annual

household income

(GHS)

Average annual

household

expenditure on

rent (GHS)

Average an-

nual per-capi-

ta expenditure

on rent (GHS)

Total annual

cash expen-

diture on rent

(million GHS)

Average

annual house-

hold expen-

diture on

maintenance

(GHS)

Average annual

per-capita

expenditure on

maintenance

(GHS)

Total annual cash

expenditure on

maintenance

(million GHS)

Year

2008 2014 2008 2014 2008 2014 2008 2014 2008 2014 2008 2014 2008 2014

Lowest

728 6,571.8 — — — — — — — — — — — —

Second

1,020 10,698.0 — — — — — — — — — — — —

Third

1,098 14,823.5 — — — — — — — — — — — —

Fourth

1,263 16,909.7 — — — — — — — — — — — —

Highest

1,544 25,200.9 — — — — — — — — — — — —

Accra

— 17,023.7 — — — — — — — — — — — —

Other

Urban

— 22,726.8 — — — — — — — — — — — —

Urban

— 20,930.1 — — — — — — — — — — — —

Rural

— 11,408.0 — — — — — — — — — — — —

Ghana

— 16,644.6 18 423.94 8 192.26 90 749.21 86 568.18 25 178.99 151 1,054.77

Table 11 • ANNUAL INCOME AND EXPENDITURE ON RENT

2524

The next tier of cities that could benefit from af-

fordable housing initiatives comprises Kumasi and

Sekondi-Takoradi. Kumasi, the capital of Ashanti

Region, is a very strong commercial centre in the

West African sub-region and is also a renowned

cultural centre. As such, it has a large population

(2.1 million in 2010), making it the second largest

city in the country. About 4% of households in

Ashanti Region live in houses unfit for human hab-

itation (GSS 2013). The region contains 16.9% of the

country’s housing stock but has the second highest

number of households per house (GSS 2013). De-

mand for housing in Kumasi is second only to that

of Accra. The coastal city of Sekondi-Takoradi has,

since the local discovery of oil in 2007, also been

growing increasingly rapidly, as substantial num-

bers of newcomers including lower-income house-

holds, move into the city region.

The third geographical area of interest is the Sa-

vannah Accelerated Development Authority (SADA)

region, which comprises the Upper West, Upper

East and Northern regions and northern portions

of the Brong-Ahafo and Volta regions. The SADA

region consists of small towns and cities including,

among others, Tamale (the largest), Wa, Bolgatan-

ga and Kintampo. The region is inhabited by more

than 4.4 million people with large household sizes

and the lowest level of expenditure on housing.

The Northern Region, for example, has consistently

recorded the highest household membership in

each censual year, with 7.7 members per household

recorded in the 2010 census. In the last four censu-

ses conducted in Ghana, average urban house-

holds' sizes in the Brong-Ahafo, Upper West and

Upper East regions were shown to be higher than

the national average (GSS 2014). Meanwhile, 1.2

households occupy one dwelling in the Northern

Region while over 35% of households in the three

northern most regions have one or two sleeping

rooms. In terms of housing quality, over 30% of the

housing stock of the three northern regions is built

with mud/earth. This area has the highest pro-

portion of such housing nationally, which means

that the quality of housing in these regions, often

regarded as the poorest in the country, needs to

be improved. Households in the rural savannah,

for example, have Ghana’s lowest mean annual

income at GHS 10,094.73 (GSS 2014).

What the above tells us is that Ghana’s affordable

housing market requires tailor-made and carefully

designed interventions that target specific market

segments. The market exhibits mixed characteri-

stics that appeal to all income groups, especially

households in the low-income category. The avai-

lability of local building materials, land and labour

could be explored further to support customised

solutions that are low cost.

D

ue to market inelasticity, emerging an-

ecdotal evidence suggests that the formal

housing supply targeted at the high-income

bracket is practically at saturation point in Accra.

Indeed, it is not uncommon for luxury apartments

to remain vacant for up to two years in the ca-

pital. Furthermore, the rents for such properties

appear to be falling from the peak levels recorded

in 2007–2009. The case has never been clearer or

more urgent for the market to refocus, moving

away from current practices that price out middle-

and low-income earners and towards delivering

housing that meets the needs of lower-income

customers.

There are several ways to identify which elements

of affordable housing offer the most exciting pro-

spects for those interested in affordable housing

initiatives – be they opportunities for improving

quality, tenure, occupancy or location. As discus-

sed previously with regard to Table 4, it is not

possible to determine housing quality merely by

considering the materials used to build it. The

actual condition of the part of the building being

surveyed (e.g. external walling) must also be consi-

dered. For instance, the 2000 and 2010 PHC surveys

do not indicate the condition of the sandcrete wal-

ling, which makes it difficult to determine the scale

of the business opportunity for those interested in

providing home improvement services. The obvious

exception to this is, of course, housing built using

materials that are patently of insufficient quali-

ty, such as tents and improvised homes (kiosks,

containers, etc.). What is required, then, are further

studies to determine the condition of the materials

used for the elements of housing in question.

A substantial proportion of households living in

rent-free situations as well as those perching or

squatting are likely to reside in relatively poor con-

ditions. In GAMA 23% of the metropolitan region’s

housing stock is occupied in these ways, in other

cities and towns this figure rises to 29%, and in

rural areas it is 27% (GSS 2014). De-crowding the

smaller dwellings, particularly the one-room and

two-room types, by adding another room would,

for the most part, substantially reduce the level of

crowding occurring within them. As these types of

accommodation are often associated with low-in-

come households and are typically found in com-

pound housing, a building extension programme

for small dwellings would have a significant impact

on affordable housing stock.

Housing demand and ability to pay differs from

one city region to the next. Of the several geogra-

phical areas identified as key locations for initi-

ating the proposed affordable housing business

models, GAMA is the most important. Here, resi-

dents have the highest per-capita income and they

spend proportionately higher amounts on housing

(16.7%). The metro region’s socio-economic, admi-

nistrative and political character acts as a magnet,

drawing large numbers of migrants into the city re-

gion each year. These migrants, who come seeking

better livelihoods, have diverse economic profiles

and come from within and outside of Ghana. The

Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA) is current-

ly home to 16% of Ghana’s population, making the

scale of the market for affordable housing in Accra

vastly bigger than in other locations. As the GAMA

has a varied population, its housing need has both

quality and quantity dimensions.

INTERESTING AREAS FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING

2726

commercial parking space

playground

S

everal governments, especially from the im-

mediate post-independence era, recognised

housing as both a basic right and a catalyst

for sustained economic development. Over time

different governments have adopted slightly diffe-

rent approaches to housing, depending on the le-

vel of priority attached to it and on the macro-eco-

nomic conditions of the period. As such, the sector

has witnessed interventions ranging from policy

and direct financing, to housing provision and

home improvement schemes, among others. A

significant proportion of these interventions were

concentrated on Ghana’s major cities. The 1986

National Shelter Strategy sought to refocus policy

towards minimal state intervention in the housing

market and on creating an enabling environment

(Bank of Ghana 2007). Since then, state interven-

tions have been diverse, covering areas including

research on and the promotion of local building

material use, land reform and the establishment of

land banks (either directly or through quasi-state

organisations).

STATE AND QUASI-STATE INTERVENTIONS

Over the years, a number of property market actors – be they state, quasi-

state, private sector, NGO, housing cooperative, and credit union – have designed

and implemented programmes aimed at delivering affordable housing. In many

instances, the cost of the end-product differs substantially from the anticipated

end-price. This section attempts to catalogue major housing interventions

in Ghana from the post-independence era to date as well as ‘successful’

interventions from non-state actors.

Affordable housing

interventions in Ghana

5

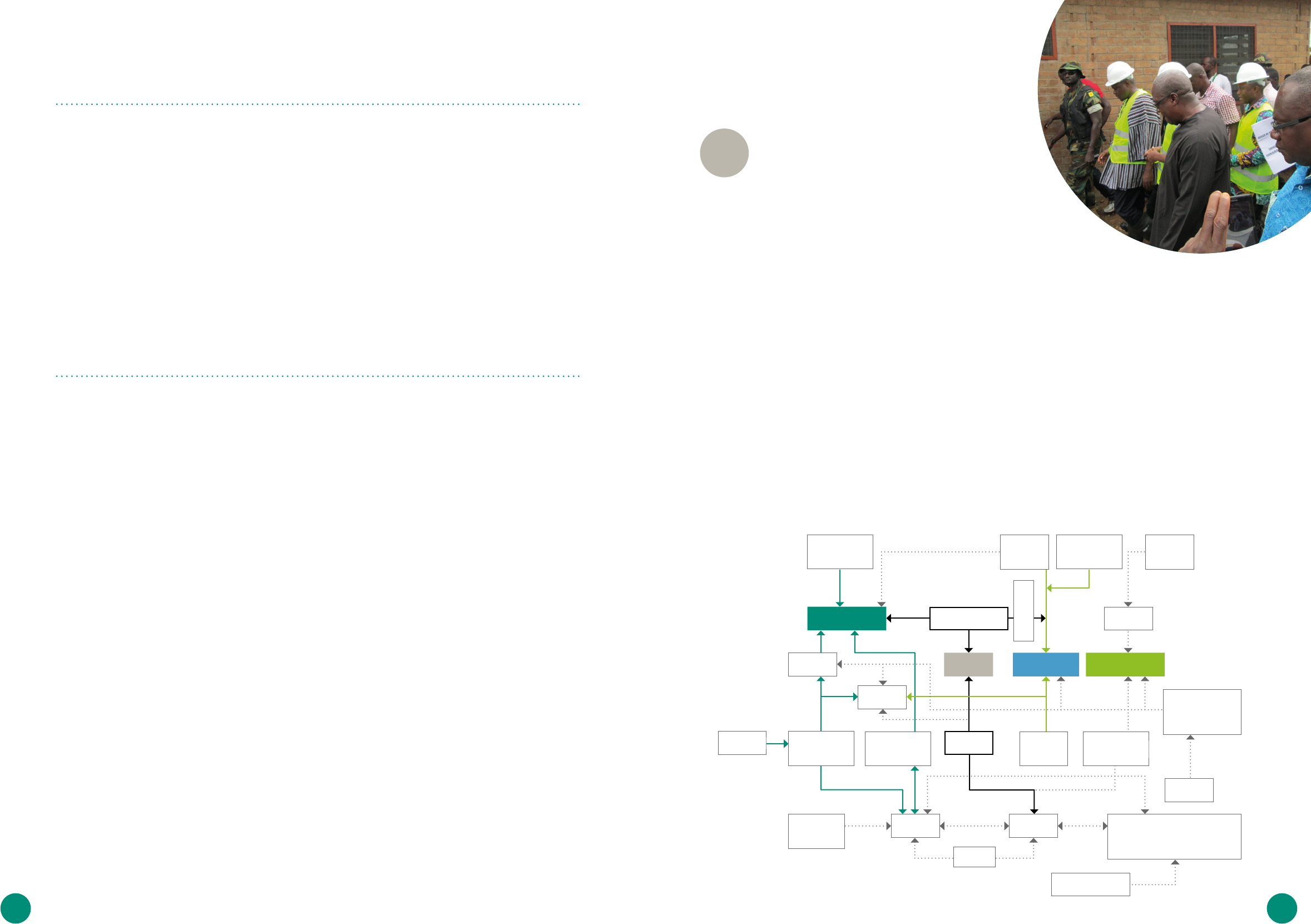

Photos: RegencyFoundation, Turelinckx, Puyvelde and Vandenbempt (2011)

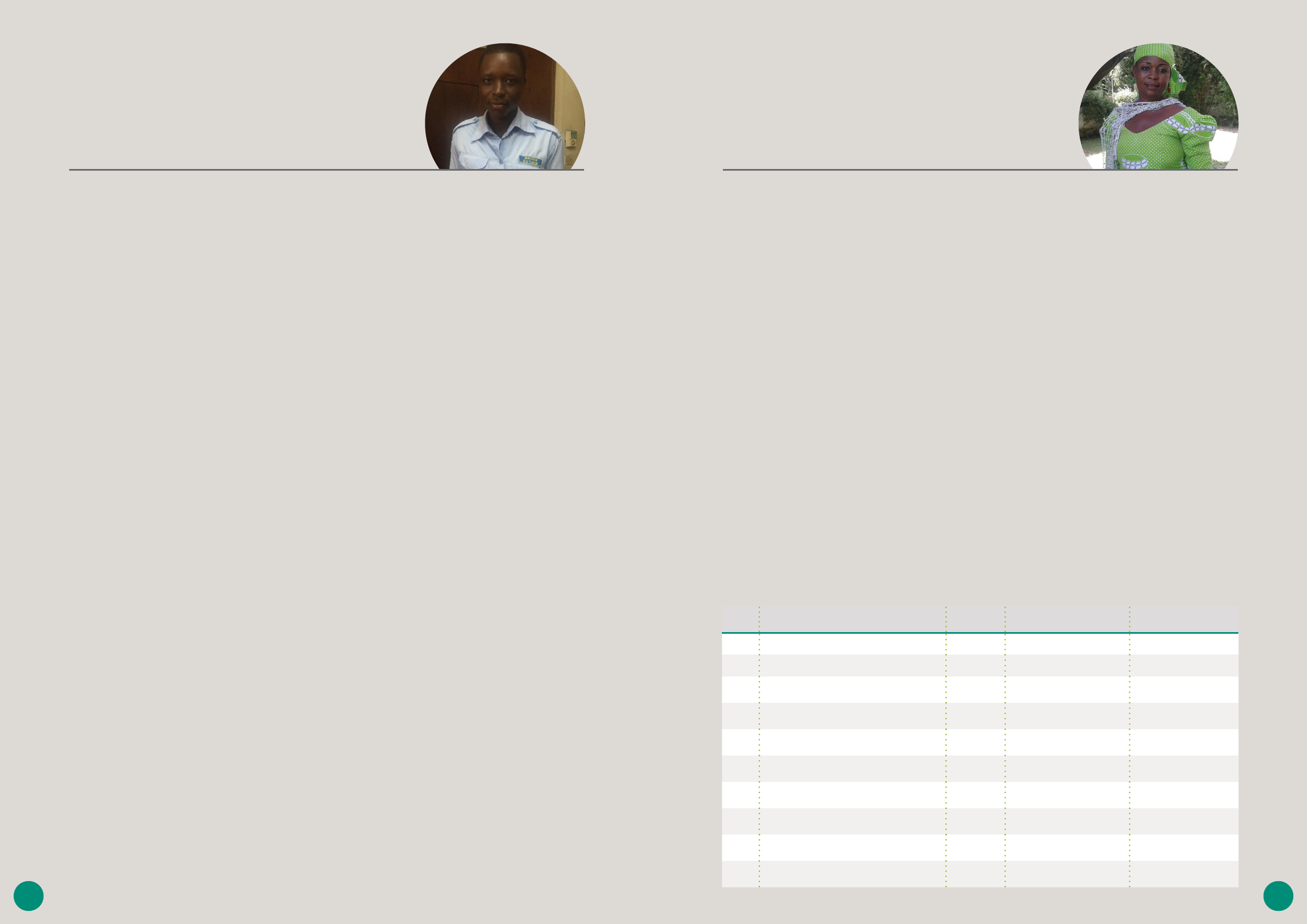

T

he 103 founding members of Tema Housing

Cooperative (THC) were low-income people

living in the Tema area, earning month-

ly incomes of around USD 50–80. Established

in 1972, the THC’s central aim was to provide its

members with affordable housing (that could be

subsequently extended). The Tema Development

Cooperation (TDC) granted the THC land sufficient

to build 105 housing units. In its first phase the

THC housing units each cost GHS 2,812 (equal to

approximately USD 2,400) and comprised a single

bedroom, a lounge, kitchen, washing and toilet

facilities plus extra foundations installed for the

optional addition of up to three bedrooms at a

later date. The project was carried out in three

phases, with phases one and two supported with

a total of GHS 168,000 in loans from the govern-

ment’s Low-Cost Housing Scheme. By 1987 a total

of 52 units, comprising a mixture of one- and

two-bedroom houses, had been completed, all of

which offered varying options for extension. At this

time, members were also in the process of building

another 48 units.

By the end of phase two, the THC had repaid

the government loan and its associated interest

charges, and had trained a number of its mem-

bers to carry out the planning and design of phase

three, which was subsequently approved by the

TDC. However, inflationary pressure in this period

devalued the THC’s savings, which prevented the

Cooperative from moving forward with the next

phase of housing. It did, however, lay the founda-

tions for the remaining 53 units and the owners

used private means to complete them. Infrastruc-

ture including road surfacing (unsealed), drains,

water and electricity connections (both off- and

on-site) and the central sewer were progressively

and wholly financed by THC members.

Owners of all the houses built in phases one and

two have since expanded their homes, adding

further rooms either for residential or commercial

purposes. This can be seen as a mark of the mo-

del’s success. Although the THC still exists and plans

to develop another phase, there is no space for any

further developments at its current site. In addition,

members also decreased their contributions to the

Cooperative once their houses were complete.

NON-STATE HOUSING INTERVENTIONS – HOUSING COOPERATIVES

Tema Housing Cooperative

2928

B

lue Rose Ltd was originally founded in 1987

as a floristry business but, in 2005, the

company decided to venture into property

development. It has since built over 900 housing

units consisting of two-bedroom terrace houses,

two- and three-bedroom semi-detached houses,

two- and three-bedroom detached houses, and

two-bedroom terraced houses, usually set within

gated communities. The housing provided targets

different segments of the market – from the working

middle classes to the top end of the upper classes.

The residents of Blue Rose estates are employed

across a wide spectrum of occupations including

teaching, nursing, law, the civil service, etc.

The cheapest unit, a one-bedroom expandable

unit, costs GHS 80,000. The most expensive unit, a

four-bedroom detached house, costs GHS 292,000

or its equivalent in another currency.

The finance to build the housing comes from com-

mercial loans from lenders including the HFC Bank.

Prospective buyers are required to make a 100%

cash payment or take on a mortgage with a com-

pulsory 20% down-payment. Mortgages are usually

arranged with the HFC Bank or Ghana Home Loans.

Additionally, a charge of GHS 3,000 is paid to cover

the documentation and utilities.

Another 1,000 two- to four-bedroom homes are

planned to be built at Kasoa near Budumburam

in 2016. In 2014, at the BID International Quality

Summit in New York, Blue Rose was awarded the ti-

tle of the ‘Most affordable real estate developer in

Africa committed to building houses to the highest

quality standards’.

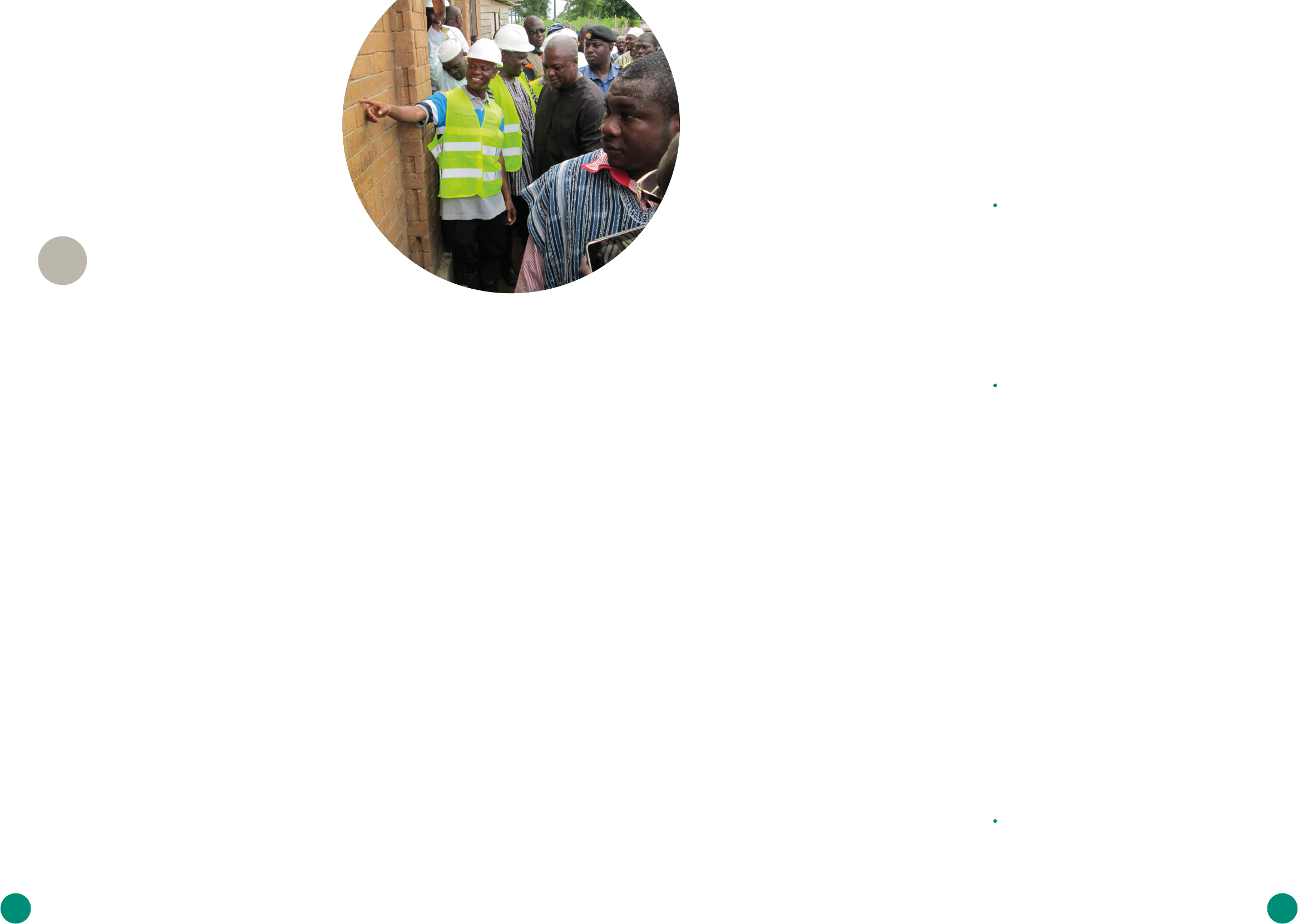

I

n 2013 the Affordable Housing Project in Tama-

le, with funding from REAL UK (a peer-to-peer

lending platform for small and medium-sized

property developers), began developing a total of

200 two-bedroom detached houses at two loca-

tions within the Tamale Metropolitan Area.

One site belongs to the Tamale Cooperative Credit

Union (TCCU), which undertook to develop the pro-

perties for its members, while the other was made

available by the Tamale Metropolitan Assembly in

order to provide housing for interested staff wor-

king in its decentralised departments. The Assem-

bly is also installing the required infrastructure at

both sites. Potential buyers were required to pay

20% of the unit cost

21

upfront, with the remainder

to be paid over five years at an interest rate of

18% per annum. In 2015 the project stalled due

to funding issues and the irregular reporting of

progress on project implementation. This has since

been resolved and, at the time of writing, work was

scheduled to resume in June 2016. By the end of

April 2016, 100 units were about 65% complete at

the TCCU site, a total of 23 units were fully comple-

te at both sites, and the remaining properties were

at various stages of completion.

PRIVATE SECTOR INTERVENTIONS

Blue Rose Ltd Tamale Affordable Housing Project

PROJECT DATA

LOCATION

Lahagu

TARGET GROUP

Active poor

TOTAL NUMBER OF

UNITS

200 units (100 at each site)

SPECIAL FEATURE

Focus on homeownership

support services

Figure 5 • A TWOBEDROOM TERRACE HOUSE

Photos: Blue Rose 2016, Water and Sanitation for Africa (2016)

3130 31

T

he TAMSUF project, implemented with sup-

port from the UN-HABITAT Slum Upgrading

Facility (SUF), promoted the development

of affordable housing units for the Amui Djor slum

community. The primary objective was to develop,

test and apply new and innovative means for

financing pro-poor urban development projects,

with an emphasis on domestic capital mobilisati-

on. UN-Habitat support involved the provision of

grants including an initial USD 400,000 for capital

enhancement and another USD 100,000 for admi-

nistration and development (Tweneboa 2011). The

project also benefited from a total of GHS 79,714 in

subsidies accruing from government’s contribution

(37%), contributions received from Peoples Dialo-

gue Ghana (43%), and the value of the land (20%).

The project built a total of 31 apartments compri-

sing a mixture of single-room self-contained and

two-bedroom apartments. The project determined

the costing for building a single-room apartment

to total GHS 6,500 but, upon completion of the

units, this cost had almost doubled (UN-HABITAT,

2011).

To make the units affordable, they were cross-sub-

sidised through the installation of 15 shop units

as well as public toilets and bathing facilities to

be rented as business ventures. This reduced the

cost of a single self-contained room and two-be-

droom apartment to GHS 6,576.68 and GHS 13,157.36

respectively (Tweneboa 2011). Beneficiary house-

holds, made an upfront payment of GHS 1,000. To

enable them receive loans, they formed a coopera-

tive group and then received loans guaranteed by

UN-HABITAT of GHS 1,500 from People’s Dialogue

22

and approximately GHS 4,000 from AmalBank, each

to be repaid within 10 years. Beneficiaries pay a

total of GHS 75 a month to service their loans.

Project managers acknowledge key challenges

including; access to the land, ability of beneficia-

ries to service loans, securing credit arrangements

for beneficiaries and some members withdrawi-

ng membership from the cooperative (Tweneboa

2011). Presently, members of the cooperative are

meeting their repayment obligations. Also, import-

antly, the cooperative has entered into negotia-

tions to purchase land adjoining its current site for

the next phase of its housing development.

PROJECT DATA

LOCATION

Amui Djor

TARGET GROUP

Slum dwellers

TOTAL NUMBER OF

UNITS

31 apartments

SPECIAL FEATURE

GHS 79,714 in subsidies

COST

Monthly rent of GHS 75 for a

one-bedroom unit and GHS

140 for a two-bedroom unit

MAIN CHALLENGE

Tenure security

Addressing the

challenges of

affordable housing

6

A

pproximately 85% of households (Figure

3) can afford housing but are currently not

considered by formal property developers.

The size of the market for affordable housing and

the dearth of affordable housing solutions on the

market presents a wide range of opportunities –

e.g. in financing, direct provision, maintenance and

servicing, etc. To benefit from these opportunities,

different schemes can be modelled to target spe-

cific pro-poor objectives and financing schemes.

Market dynamics coupled with population growth

and urbanisation provide a significant basis for

affordable housing provision in the country in the

medium to long term.

When it comes to investing in real estate, the sup-

ply gap is now in affordable housing. The density

of market demand is, however, unevenly distribu-

ted across the country. The major cities present a

cross-section of all affordable housing needs and

have the highest demand for affordable housing.

Similarly, a significant proportion of the estima-

ted GHS 1.2 billion affordable housing market is

based in urban areas; in rural areas, the need

for affordable housing is more tied to improving

housing quality. Affordable housing solutions must

therefore be designed to target the specific needs

of households in all these different contexts.

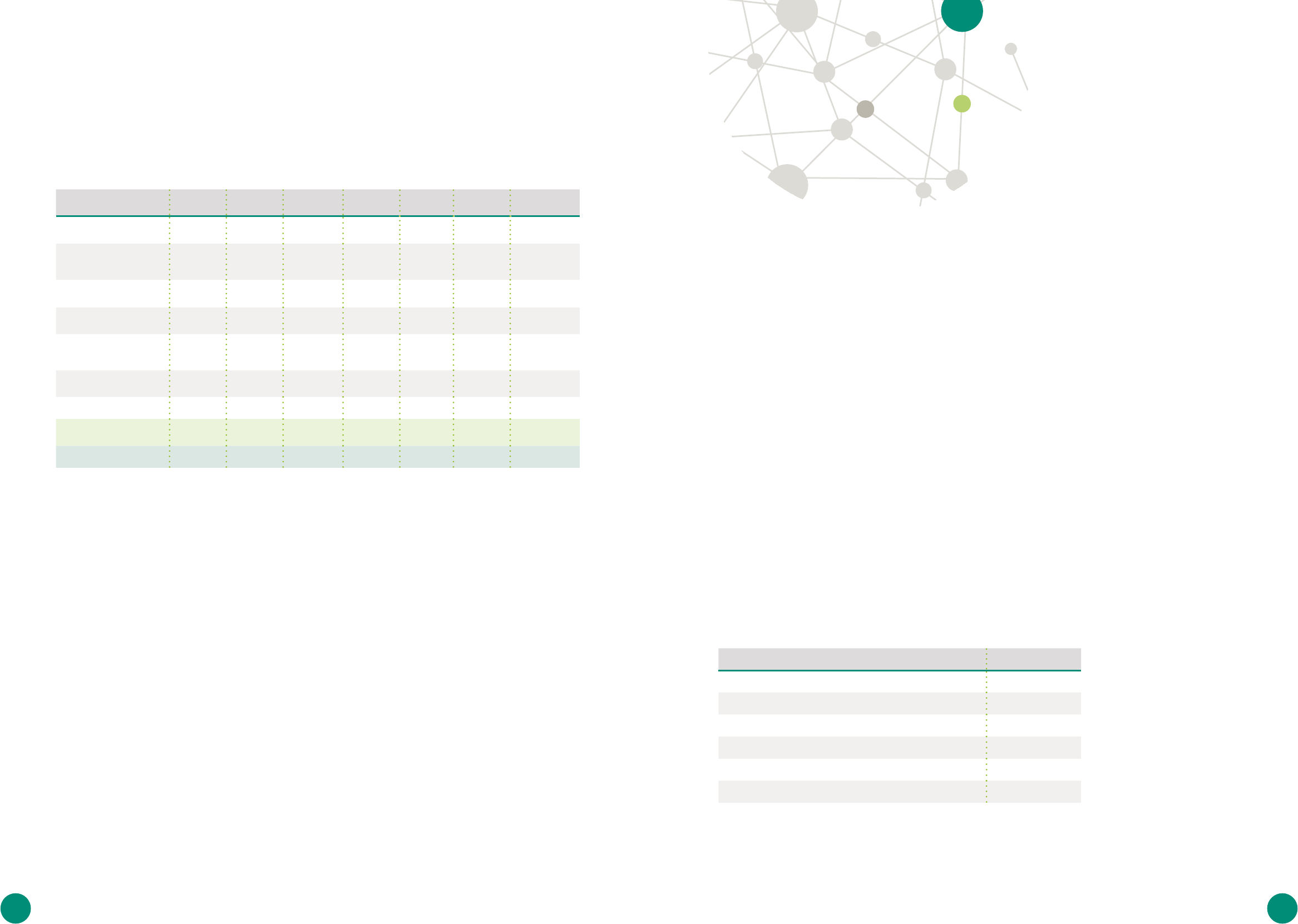

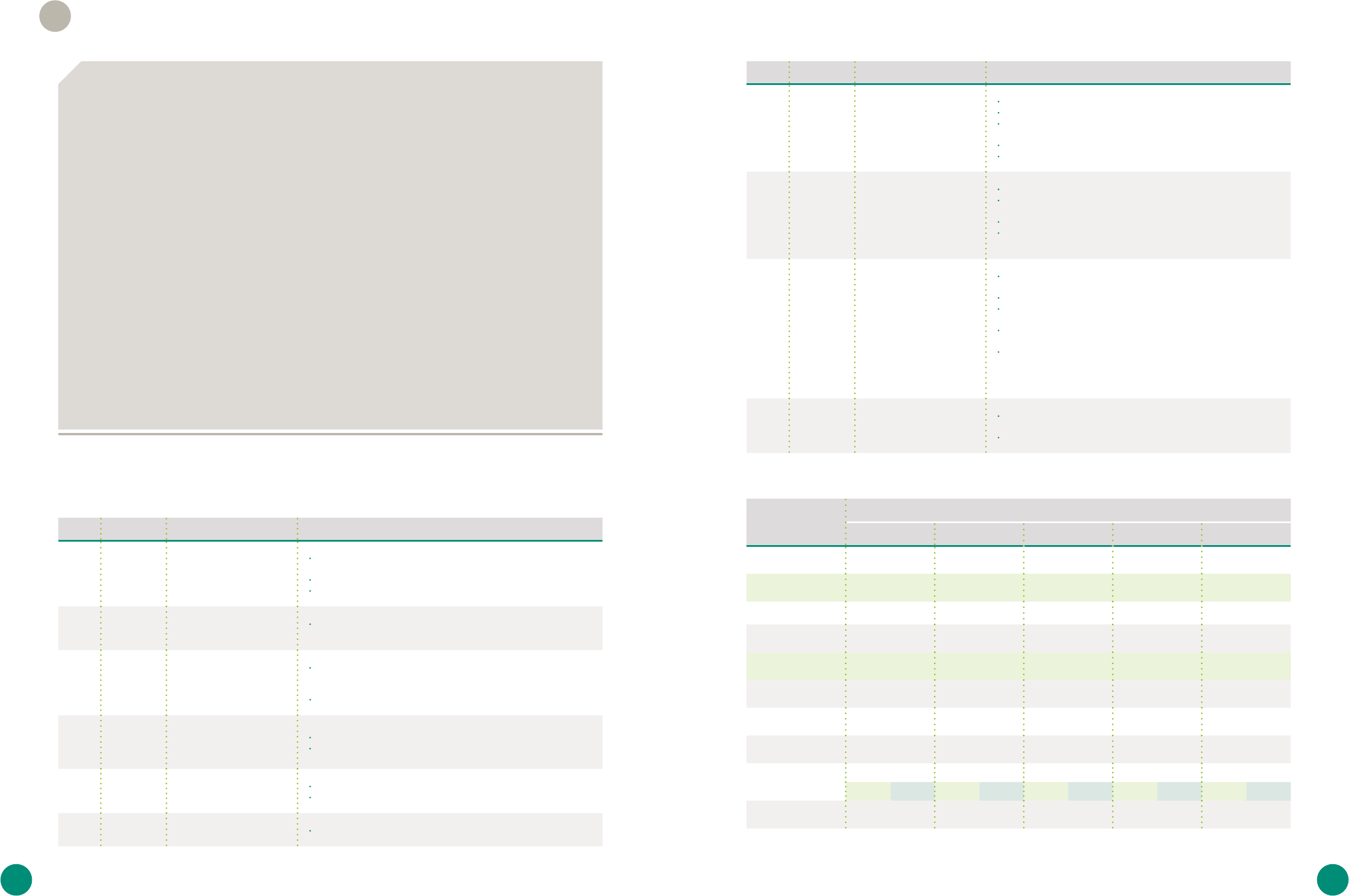

T

hose providing affordable housing need to

consider the whole value chain of housing

provision, which involves four main stages

(Figure 6). The first stage involves land acquisition,

planning, design and the acquisition of permits for

the proposed housing. The cost of land, administ-

rative processes to acquire titles and permits, and

on-site infrastructure constitute the first hurdles to

delivering affordable housing. For instance, it takes

around three months to secure the land titles for a

plot of land rented under customary tenure, which

is not only slow, but also incurs high transaction

costs. Cutting the bureaucracy and transaction

costs involved would help to accelerate the pace of

housing delivery.

The second stage, production and construction,

involves three main overarching approaches: home

extensions, maintenance and retrofitting, and new

home construction.

SIZE OF THE AFFORDABLE HOUSING MARKET

THE HOUSING VALUE CHAIN

TAMSUF Affordable Housing Project in Ashaiman Municipality

Sourcing

& design

Production &

construction

Sales &

marketing

Maintenance,

deconstruction

& recycling

23

Photos: RegencyFoundation, Tweneboa (2011)

Figure 6 • THE HOUSING VALUE CHAIN

3332

H

ouseholds currently living in units abo-

ve the two-persons-per-room threshold