The African

Consumer

and Retail

Sector Report

kpmg.com/africa

Table of contents

Overview 1

Key Drivers 2

Demographics 2

Macroeconomic Environment 3

Impact of Lower Oil Prices 7

Incomes and Spending Patterns 8

Consumer Traits 12

Challenges 13

Retail Markets in a Selection of Key African Economies 15

Egypt 17

Ghana 18

Kenya 19

Morocco 20

Nigeria 21

Sources of Information 24

Contact Details 25

The series has the following reports:

• Banking in Africa

• Private Equity in Africa

• Insurance in Africa

• Power in Africa

• Healthcare in Africa

• Oil and Gas in Africa

• Construction in Africa

• Manufacturing in Africa

• Fast-Moving Consumer Goods in Africa

• Luxury Goods in Africa

• White Goods in Africa

• Agriculture in Africa

• Life Sciences in Africa

1 | The African Consumer and Retail The African Consumer and Retail | 2

Africa is home to more than one billion people, presenting a

massive potential consumer market. Moreover, population

growth remains rapid, and the United Nations (UN) Population

Division forecasts that the continent’s population will surpass

the 1.5 billion mark by 2026 and the two billion mark 15 years

later. In addition, Africans are increasingly moving to cities,

making it easier for companies to target certain consumer

groups. Although the demographic make-up of the continent

is extremely favourable, success is not guaranteed. Firstly,

there are vast differences across countries – North Africa

is for example far more developed than sub-Saharan Africa

(SSA), while the retail market opportunities in countries

will differ due to variances in consumer tastes, culture,

income, and demographics. Secondly, it is important to

distinguish between opportunities at the national and at the

city level. Data at the national level can often be misleading,

as a city’s GDP per capita can vastly exceed the national

average due to the greater concentration of wealth in

some urban areas. Finally, simply because a country has

favourable demographics does not mean that this will

necessarily translate into higher levels of economic growth

and consumer spending. An increase in the proportion of the

working-age population relative to the total population (the

so-called demographic dividend) is potentially beneficial for

consumer spending as it frees up resources. But this will not

happen if there is a high unemployment rate in the working-

age population.

Africa’s retail sector remains relatively under-developed

at present, with most shopping being done at traditional

shops. The formalisation of the sector will be a key trend

underlying the sector’s expansion in the coming decade.

The lack of physical infrastructure has been one of the main

constraints to the entry of formal retailers, as there are simply

not enough shopping centres available at present, while

bureaucratic obstacles and land issues further complicate

matters. At present, most African consumers – especially

south of the Sahara desert – remain extremely poor and

spend most of their money on food and other necessities.

This makes for a promising outlook for fast-moving consumer

goods (FMCG) companies given the large market to cater for.

Crucially, an increasing number of consumers are on the cusp

of the US$1,000 annual income level, which will allow for the

expansion of consumption beyond just the basics. Retailers

will be looking to take advantage of the large market at the

low end, while gradually starting to offer these consumers

higher-value products.

The aim of this report is to analyse the key drivers of the

retail market in Africa, including key demographic and

macroeconomic factors, as well as spending patterns. In

addition, we consider the broad outlook for the sector and

highlight the countries we expect will have the strongest

growth rates in the sector

over the long term.

KEY DRIVERS

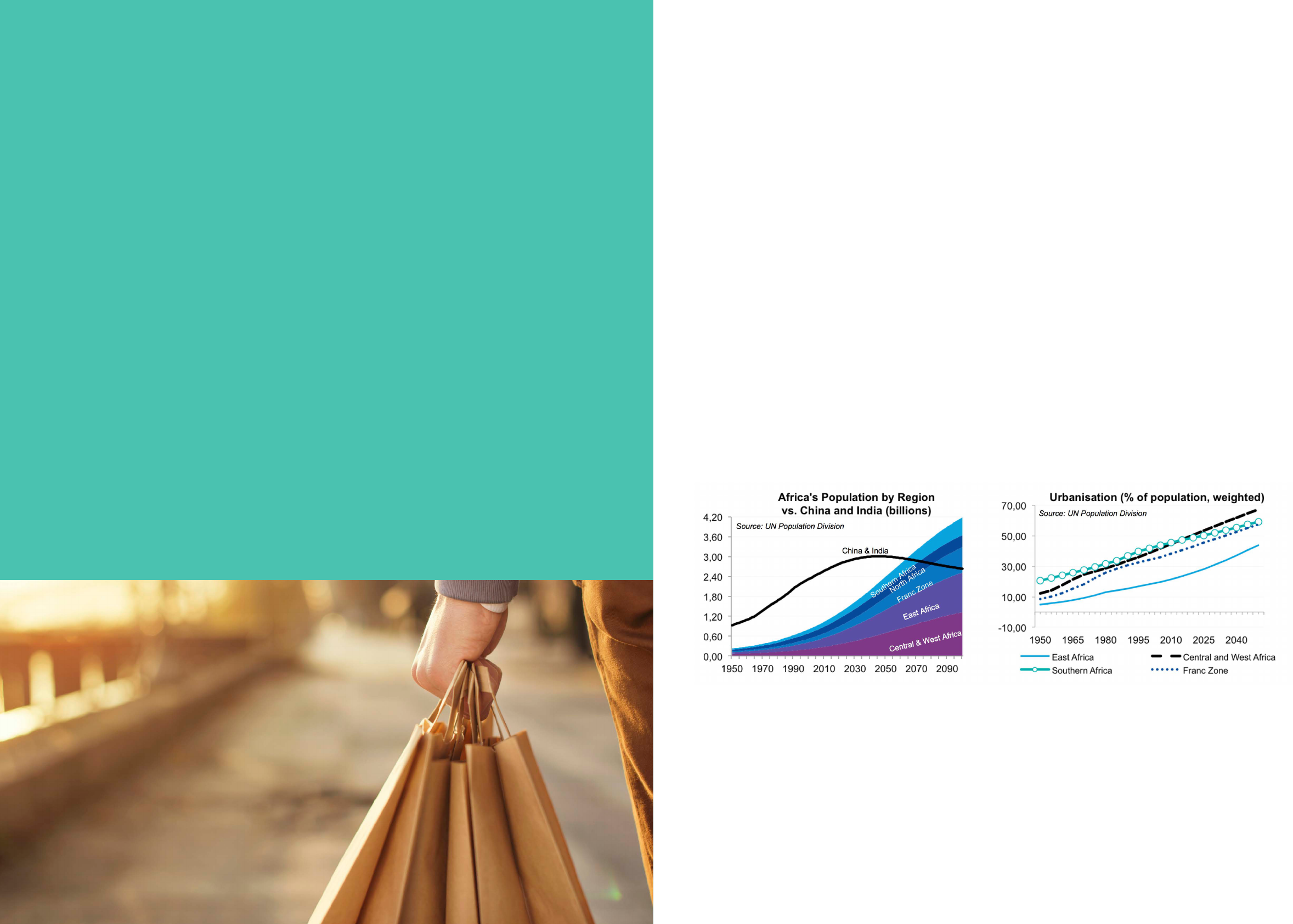

Demographic factors underpinning Africa’s retail sector

expansion include:

• A large population – estimated at just over 1.1 billion in

2014. SSA accounts for 81% of Africa’s total population,

while Nigeria accounts for around a fifth of the SSA total.

Other countries with notable population sizes include

Ethiopia, Egypt, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo

(DRC). These four countries account for 38% of Africa’s

total population.

• Population growth rates are still relatively high. This trend

is confined to SSA countries, as population growth rates

in North Africa have already declined significantly on the

back of lower fertility rates. In turn, this trend is in line with

differences between the stages of economic development

that the regions find themselves in.

• Urbanisation rates are rising. The effect of urbanisation

on economic growth – or vice versa – is dependent on

job creation, the economy’s structure, and – crucially

– the definition of urban areas. UN figures indicate that

in SSA, the urbanisation rate increased from 11.2% in

1950 to 24.1% in 1980, and 36.4% in 2010. (Note that

this is a weighted average.) The UN forecasts that SSA’s

urbanisation rate will reach 45.9% by 2030 and 56.7% by

2050. The urbanisation rate of East Africa is much lower

than the rest of SSA. In 2010, East Africa’s urbanisation

rate was almost 17 percentage points lower than that of

the Franc Zone, which has the second lowest rate on the

continent. East Africa’s low level of urbanisation can be

ascribed to the substantial importance of subsistence

agriculture in most of these countries.

• Beneficial changes in the age structure. The composition

of the population is crucial, as a large proportion of children

and/or elderly in a population (i.e. a high dependency

ratio) implies that the working population will have fewer

resources to save and spend. The dependency ratio is

therefore very important for forming a view on the outlook

for consumer spending.

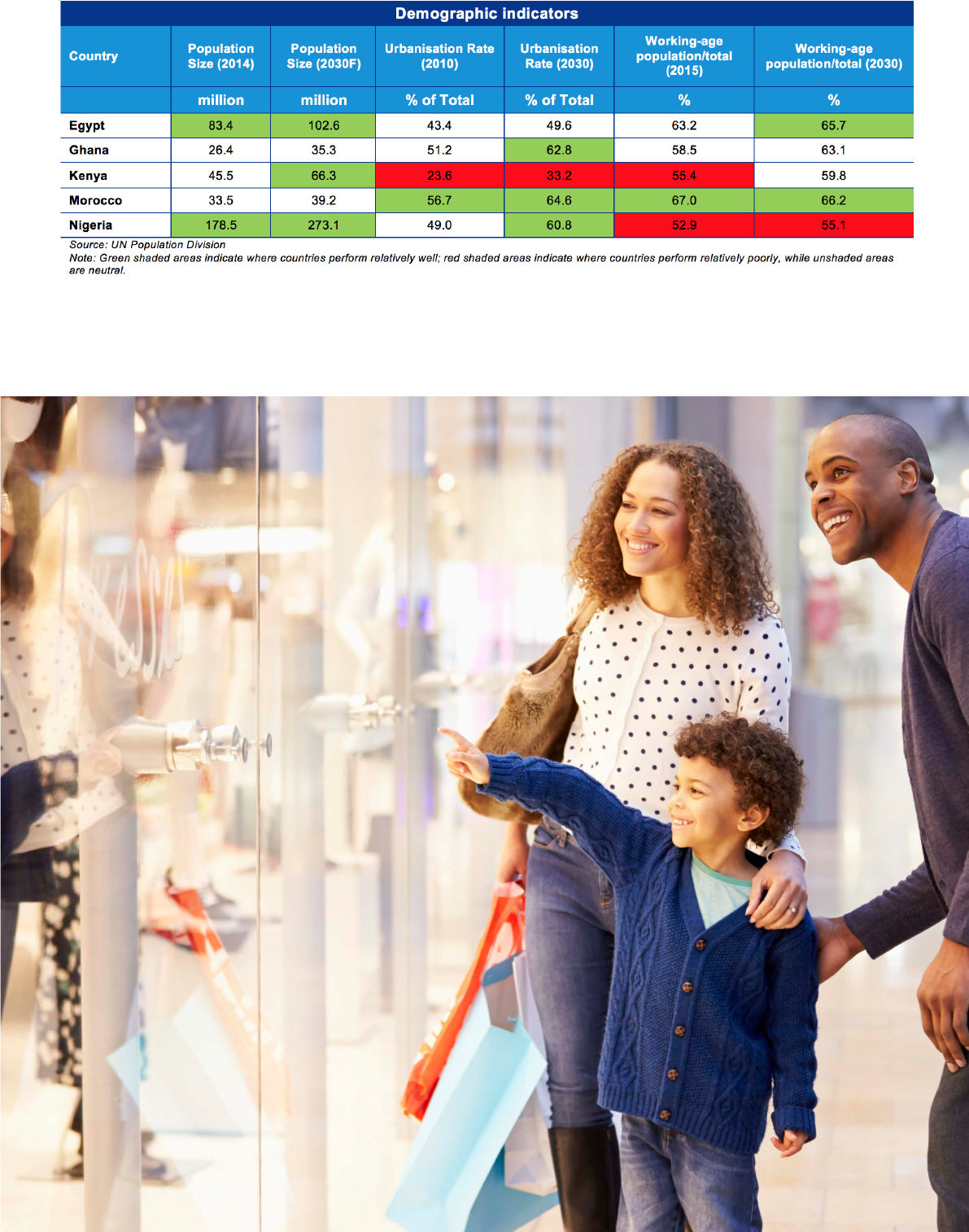

Taking the above factors into account, we have developed a

Demographic Potential Index (DPI) for 30 African countries,

which is shown in the accompanying graph. The index value

can potentially range from zero (worst outcome) to 10 (best

outcome). Due to its large population size, Nigeria performs

the best by far. On the other hand, countries that outperform

significantly relative to their population sizes include Gabon,

Libya, Botswana, Tunisia, and Mauritius. These countries

have the potential to benefit from demographic shifts

despite having relatively small population sizes, due to either

having an urbanised population, or due to the working age

population accounting for a sizable proportion of the total.

Meanwhile, countries that perform notably worse than their

population sizes would suggest, include Uganda, Malawi,

Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, and Ethiopia. For comparison

purposes, note that China’s index value is calculated as 8.8.

Demographics

OVERVIEW

Africa’s economic performance has improved greatly since

the turn of the century, leading to notable gains in GDP

per capita and lower levels of poverty. During 2001-13, the

SSA economy grew at an average rate of 6.3% p.a. in real

terms, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF),

compared to 2.9% p.a. during the previous 13-year period.

This meant that nominal GDP per capita rose from US$571

in 2001 to US$1,750 by 2013 after having declined during

the previous two decades. The expansion coincided with

an improvement in business environments and a reduction

in political risk, although a commodity boom also played a

significant role in the increase in real GDP. In addition, several

African countries are expected to be among the fastest

growing in the world over the next decade.

A key question is whether there will be the complementary

economic reforms that are needed to ensure that economies

benefit from demographic shifts, since a large working age

population will count for nothing if unemployment is rampant.

Apart from economic policies and reforms, other factors

that are crucial to ensure that a country can benefit from

demographic shifts are the effective mobilisation of national

savings and a relatively skilled labour force.

In order to determine which African countries would be

best placed to take advantage of their demographic profiles,

an Economic & Investment Potential Index (EIPI) has also

been developed. The following indicators were included in

the index:

• GDP per capita – a proxy for wealth.

• Real GDP growth outlook.

• Main commodity export product as a percentage of the

total – measure of diversity, exposure to shocks, and

inequality.

• Ease of doing business.

• Financial market development – ability to mobilise savings.

• Consumer price inflation – measure of macroeconomic

stability, and effect on consumers’ purchasing power.

• Labour market efficiency – labour market flexibility has an

effect on employment levels.

• Political risk with a medium- to long-term outlook.

• Business costs of crime and violence.

Macroeconomic Environment

3 | The African Consumer and Retail

The countries that perform the best on the EIPI are generally

those with good business environments. Four of the top five

countries are from Southern Africa, with the only exception

being Rwanda, a country that has made significant strides

to encourage investment over the past decade. Apart from

a favourable business environment, low political risk, and

stable economic policy making, the economy is also not

overly dependent on any single commodity for exports, and it

is expected to grow strongly. On the other hand, Rwanda still

has a very low GDP per capita and it also performs poorly on

the DPI. North Africa’s performance is highly varied. On the

one hand, Morocco and Tunisia perform well thanks to their

diversified economic structures, solid business environments

and high GDP per capita (by African standards). On the other

hand, Algeria and Libya are at the bottom of the rankings

(despite high GDP per capita) due to their dependence on oil,

challenging business environments, high political risk, and

weak economic growth prospects.

Gabon’s performance is also quite good – perhaps better than

would be expected a priori. This is due to the country’s large

GDP per capita, although this could be slightly misleading

as GDP is inflated by its oil sector. Two other oil-exporters

– Angola and Nigeria – languish at the lower reaches of the

rankings due to challenging business environments and

commodity dependence.

Comparison with the 2014 Index

The top five positions remained unchanged compared to

a year earlier. One of the big movers was Morocco, which

surpassed both Tunisia and Ghana to move into sixth position

thanks to further improvement in its business environment,

and to a lesser extent a drop in inflation. Notably, Nigeria’s

ranking on the EIPI deteriorated by three positions despite

a large increase in its GDP per capita following the rebasing

of its GDP. This is because its score deteriorated in almost

all of the other components of the index. Further down

the rankings, both Mozambique and Tanzania’s rankings

improved notably. Mozambique’s ranking improved by three

positions to 12th on the back of an improvement in its World

Bank Doing Business ranking and a decrease in inflation. In

turn, Tanzania’s ranking improved by four positions to 13th.

This came on the back of a 47% increase in GDP per capita

following a rebasing of GDP, as well as an improvement in the

business environment.

Although still having poor rankings, both Egypt and Angola’s

rankings improved by three places compared to last year.

In Angola’s case this was due to an increase in GDP per

capita. In Egypt’s case, there were notable improvements

in its business environment and political risk. In the short to

medium term, Egypt’s consumers are expected to struggle

due to large fuel price increases (as the government cut

subsidies), high inflation, a weakening currency, and high

unemployment. However, if the new government under

President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi sticks to its planned reform

programme, then longer-term prospects for the economy

are bright. The country that deteriorated the most is Libya,

with its ranking slipping from 13th to last (27th). Uganda and

Nigeria’s rankings weakened by three places each, while

Ghana’s ranking slipped from seventh to ninth.

The African Consumer and Retail | 4

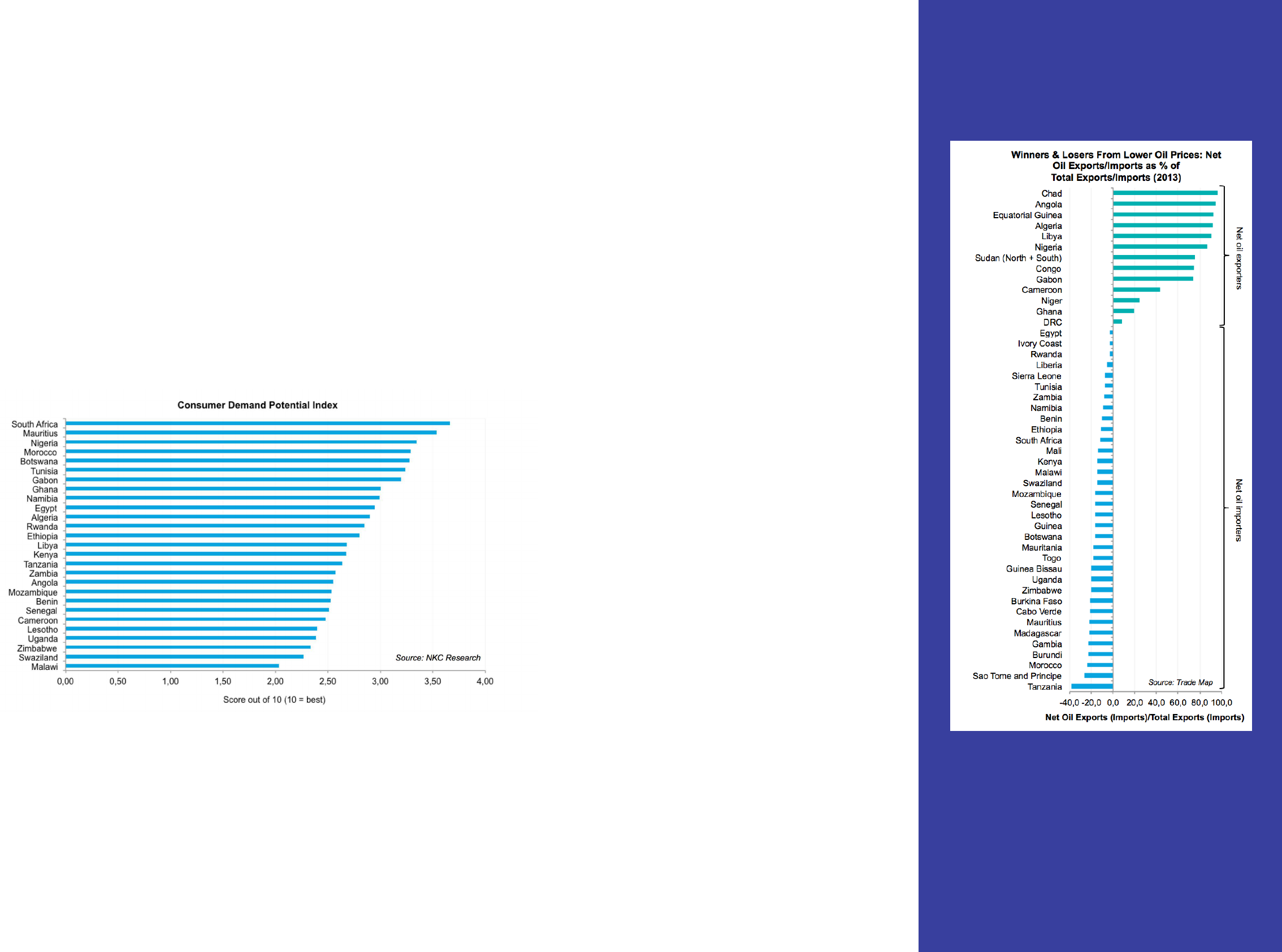

Consumer Demand Potential Index (CDPI)

Combined, the DPI and EIPI aim to identify countries with the

biggest potential growth in consumer demand. This is shown

in the accompanying graph, where the two indices were given

equal weight. As in last year’s report, South Africa, Mauritius

and Nigeria claim the top three positions. These three

countries differ substantially from one another. South Africa

has the most developed retail sector and has a fairly consistent

performance across all sub-indices of the CDPI. Mauritius

has one of the smallest populations on the continent, which

constrains its DPI, but this is counterweighed by its diversified

and well-managed economy and relatively rich population.

In stark contrast, Nigeria offers investors with a very large

potential market, but with risk, as it also has a very challenging

business environment.

In fourth place, and moving up two places since last year, is

Morocco. The country’s demographic make-up is reasonably

favourable, with a young population, rising urbanisation, and

growing middle class.

In addition, a marked improvement in the country’s business

environment is now also making it easier for retailers to enter

the market. The country is also becoming an increasingly

important gateway to Africa for European companies.

Botswana and Tunisia also perform well on the index thanks

to its fairly young and urbanised populations, and solid

business environments. However, both countries (especially

Botswana) have small populations, which reduces their

appeal for retail companies.

Gabon has held on to the seventh position, as the country

has a good demographic profile combined with a high GDP

per capita, which means that there is still a relatively large

consumer market to cater for, despite significant drawbacks.

Although Ghana has significant short-term challenges (large

twin deficits and a depreciating currency), it does quite well in

the CDPI since it is generally welcoming to foreign investors,

has a favourable demographic profile, and has strong

medium-term economic growth potential.

Comparison with the 2014 Index

The countries whose CDPI scores increased

the most over the past year were Egypt and

Benin. Regarding the latter, its score was

boosted by the fact that it was ranked as one of

the top 10 best reformers in the World Bank’s

most recent Doing Business index. Two other

countries worth mentioning are Tanzania and

Mozambique. Although still only ranked 16th and

19th respectively, their rankings are on an upward

trend. These two countries still have extremely

low income levels, with Tanzania’s GDP per capita

at only US$955 and Mozambique’s at US$647.

Therefore, over the short to medium term, retail

will continue to focus on the lower-end of the

income spectrum with FMCG companies being

most prominent. However, both countries have

strong economic growth prospects, and the

development of their natural gas industries holds

exciting long-term prospects due to the additional

foreign exchange and fiscal revenues it will

bring into the country as well as the opportunity

for companies to provide services in the gas-

producing regions.

Three countries’ CDPI scores deteriorated fairly

significantly over the past year, the most severe

of which was Libya, which is in the midst of a

civil war. The other two were Zambia and Ghana.

The deterioration in Zambia’s score was mainly

due to its Doing Business ranking rising from

83rd globally in 2014 to 111th globally in 2015. In

recent weeks, though, there have been signs of

improvement, as the Lungu administration has

reversed some controversial mining laws and we

expect it to follow a more rational and business

friendly approach in its dealings with foreign

investors than the previous regime. Ghana’s score

weakened on almost all the sub-indices, with the

most important contributors to the deterioration

being lower GDP per capita, lower real GDP

growth prospects, an increase in political risk,

and a weaker rating on the Doing Business index.

The core of the problem for Ghana, though, is its

weak fiscal finances, which have contributed to a

widening current account deficit, a depreciating

currency, increasing levels of inflation, high

interest rates, and an increase in tax rates. All

these factors, in addition to ongoing energy

shortages, are likely to keep real GDP growth

under pressure over the short term.

5 | The African Consumer and Retail The African Consumer and Retail | 6

7 | The African Consumer and Retail The African Consumer and Retail | 8

As a continent, Africa is one of the world’s largest net oil

exporters. Therefore, the sharp drop in oil prices since

mid-2014 is expected to have a negative impact on Africa’s

aggregate economic growth prospects. However, it is worth

reiterating that Africa is not one big country; indeed, the

majority of African economies will be benefited greatly from

the drop in oil prices. The accompanying graph illustrates this

by showing the following:

• In the red bars: net hydrocarbon exports (i.e. exports

minus imports) as a percentage of total exports for net oil

exporters; and

• In the grey bars: net hydrocarbon imports (i.e. imports

minus exports) as a percentage of total imports for net oil

importers.

The countries at the top of the chart – those that are most

dependent on oil exports – will be severely negatively

affected by the drop in oil prices. Nigeria, for instance, has

already devalued its currency by more than 20% since the

start of November and pressure on the currency will remain

strong as long as oil prices remain low. In turn, this pushes

up the cost of imports, which hurts consumers’ purchasing

power. Meanwhile, Angolan banks have restricted foreign

exchange transactions due to the lower availability of dollars.

This has made it difficult for foreign companies to repatriate

profits or to import goods. The government has also put

import restrictions on a wide variety of products. This has

already had a negative impact on consumer goods companies

operating in the country, especially those that need to import

their products. In addition, the Angolan government (which

subsidised fuel products) has raised fuel prices by 50% since

the end of 2014 in order to cut subsidies in support of its

budget. In mid-February 2015, the government also slashed

its budget for the year by 35%.

The top nine economies in the graph (up to Gabon) are all

highly dependent on oil, especially their fiscal finances.

Therefore, their governments will be forced to respond to

the drop in oil revenues by reducing fiscal spending, which

could have knock-on effects for employment (especially

in the construction sector if the government cuts public

investment), wages, and subsidies, all of which will affect

consumer spending. (Possible exceptions are Algeria and

Libya, who have exceptionally large stocks of forex reserves,

which they could use to finance spending.) Although

many of these economies will still offer strong long-term

opportunities, it is important to take note of the risks that

emerge when oil prices are low.

As shown in the graph, the vast majority of African countries

are net oil importers and will therefore benefit from the

drop in oil prices. Most notably, consumers will benefit

from a sharp drop in fuel prices, which will increase their

ability to spend on other products. There will also be a

notable decrease in their import bills, which will lead to an

improvement in their current account balances and therefore

the availability of foreign exchange. Morocco, for instance,

struggled with a very large current account deficit in recent

years, largely due to its large oil import bill. As a result of this,

commercial banks struggled with tight liquidity conditions

in recent years, which constrained credit growth. Now with

the current account balance set to improve, banking sector

liquidity should also improve, thereby facilitating lending,

which in turn is expected to boost investment in new and

existing businesses, which would boost employment. With a

few notable exceptions, countries in Southern and East Africa

will tend to benefit the most from the drop in oil prices, while

West Africa will be the hardest hit.

Impact of Lower Oil Prices

INCOMES AND

SPENDING PATTERNS

The African Development Bank (AfDB) estimates that the

size of the African middle class was 350 million people in

2010, or 34% of the population. The AfDB’s definition of the

middle class is daily per capita consumption expenditure

of between US$2 and US$20. However, there is a lot of

criticism against this definition, as it includes people that can

barely make ends meet. After all, the World Bank uses the

US$2/day benchmark as a poverty line. One can hardly be

considered middle class by spending only US$720 a year. The

AfDB acknowledges as much, referring to people spending

between US$2 and US$4 per day as the ‘floating class’ – a

vulnerable group that could easily fall back into poverty.

According to David Cowan, a senior economist for Africa at

Citi, a more realistic definition of middle class in emerging

markets is income of at least US$13.7 per day, which is

enough to allow consumers to purchase durable products.

This is equivalent to around US$5,000 per year.

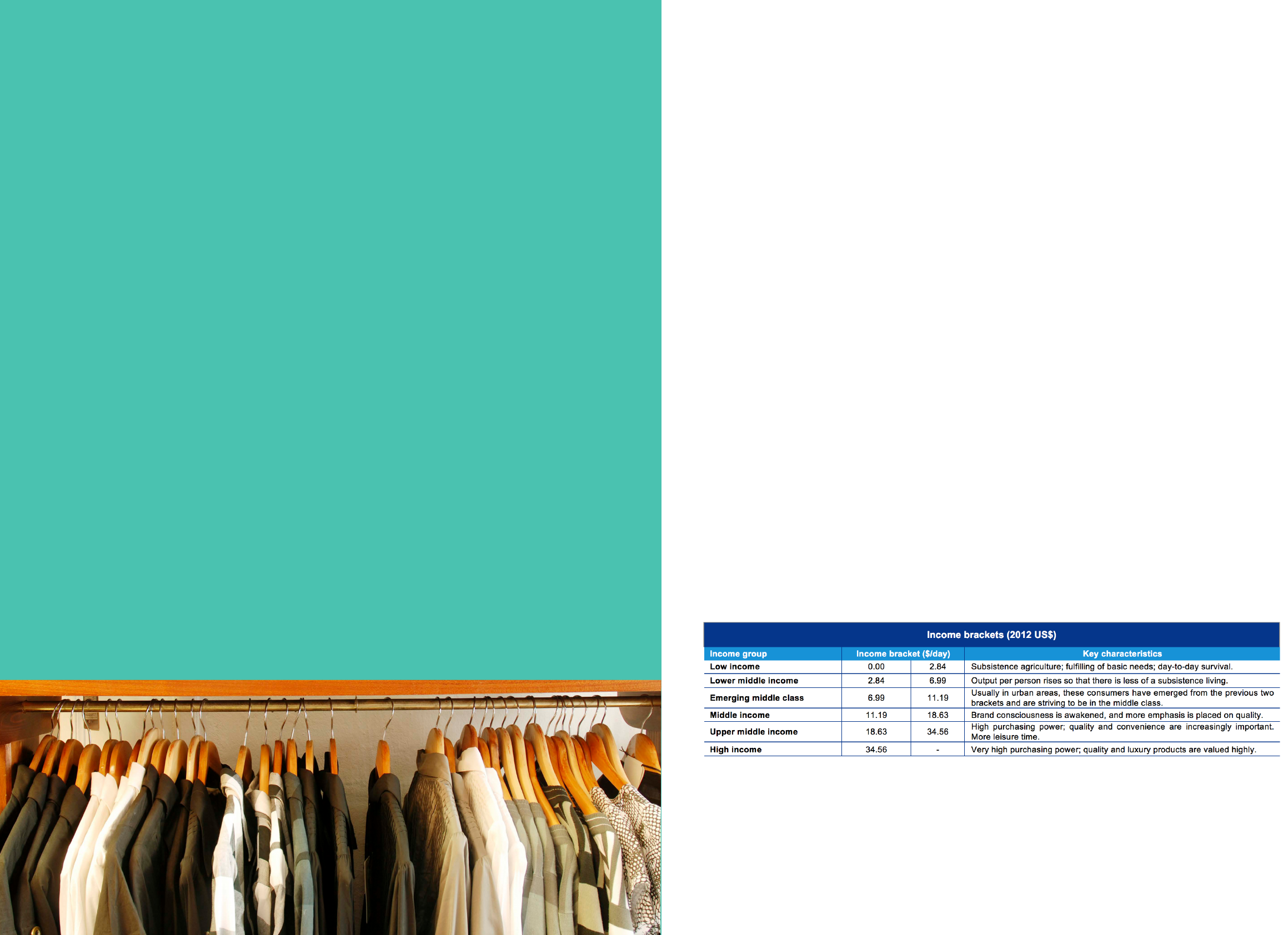

The following table, which is loosely based on the World

Bank’s classification, provides a breakdown of income

brackets, as well as the key characteristics of these groups.

As we discuss below, most Africans south of the Sahara

are still clustered within the low income grouping. For

these people, the focus is merely on survival. Consumption

decisions therefore centre on the fulfilling of basic needs

and are only made with a short-term outlook. People in this

category usually live a subsistence living, with little left for

savings. As people start to move away from a subsistence

lifestyle, output per person rises, moving them into the lower

middle income group. People in the emerging middle class

have usually migrated to urban areas in search of better job

opportunities. Once people start to earn more money and

move into the middle income group, brand consciousness

is awakened and more emphasis is placed on quality. The

upper middle income group is categorised by very high

purchasing power and increased leisure time. The quality

and convenience offered by products and services become

increasingly important. Finally, people classified in the high

income group have extremely high levels of purchasing

power, and quality, convenience, variety, and luxury are

valued greatly.

Defining the Middle Class

9 | The African Consumer and Retail The African Consumer and Retail | 10

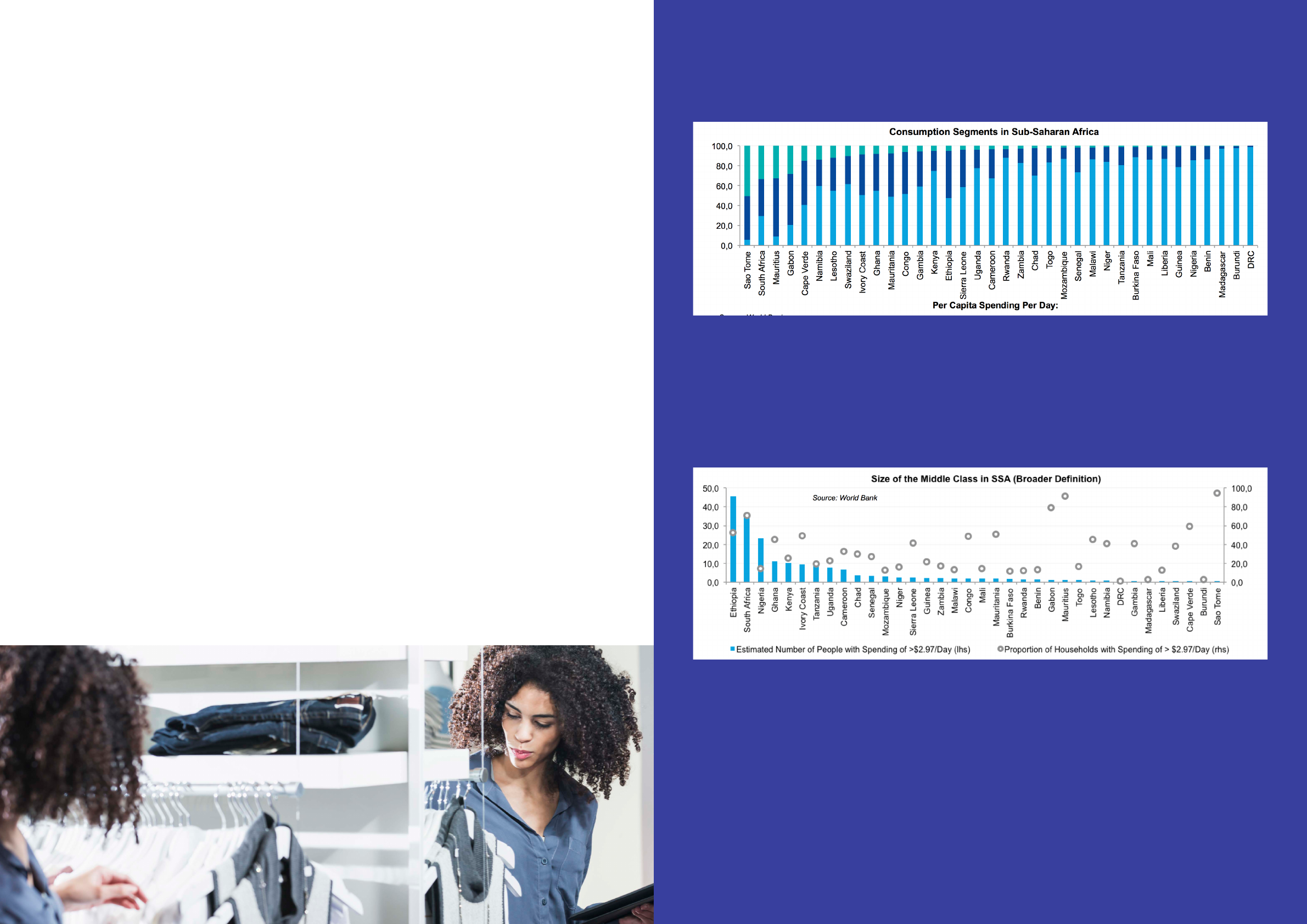

In order to get an idea of the size of the middle class in SSA

countries, each country’s population was multiplied by the

share of households that have per capita spending of above

US$2.97 per day. There are problems with this method.

Notably, the household consumption data are based on

survey data, and the World Bank notes that the sample

sizes, particularly for the higher consumption segments,

“may be very small and not representative”. Nevertheless,

it could still provide valuable insights into the potential

market size of SSA countries. In the first of the two graphs,

a broader view of the middle class is taken, similar to the

one employed by the AfDB study, and all households with

per capita spending of more than US$2.97 per day are

included. This gives a total SSA middle class of 200 million

people, 63% of which live in Ethiopia, South Africa, Nigeria,

Ghana and Kenya.

Spending patterns are determined by disposable income per

capita, in addition to other factors such as tastes, culture,

and idiosyncratic preferences. Despite cultural and regional

factors having an impact on consumer spending patterns

and trends, one generally finds quite a strong positive

relationship between income per person and consumption

per capita for various goods irrespective of these other

factors. This enables the mapping out of a generalised

spending pattern across the income bracket. At the lowest

income bracket, there is very little money (if anything) left

to spend after basic needs have been met. Therefore, at the

bottom of the income bracket, consumption is mainly on

food, much of which has been produced on a small plot of

land rather than purchased. Any excess production is then

bartered or sold in order to pay for other necessities such

as clothing and shelter. As soon as people start producing

more than they consume, funds become available to spend

on more than just the basics. The US$1,000 income level

has been identified as an important barrier that if reached,

allows for an expansion in the amount and type of consumer

products that can be afforded. The first important trend is

an expansion in the amount of food consumed, in order to

boost the daily caloric intake to healthy levels. Following

this, a further increase in income will allow for a switch to

better quality and/or more convenient foods, for example

the gradual introduction of meat and processed food into the

diet. Some of the first non-food products to benefit from the

expansion of annual income beyond the US$1,000 level are

beer, soft drinks, and prepaid mobile phones.

Moving into the emerging middle class allows for further

increases in quantity and quality. For example, consumers

will start shifting from unbranded beers to branded beers –

first to economy brands, and later on, to premium brands.

Eventually, when incomes increase even further, consumers

will start shifting away from beer towards products that are

viewed to be more sophisticated, such as brandy, whisky, and

wine. Even in this consumer bracket, further differentiation

is possible, i.e. from mainstream to premium products. The

same types of shifts occur for other consumer products, e.g.

switching from chicken to red meat or from carbonates to

energy drinks.

Spending Patterns

The first graph in this section shows the breakdown of

households by their per capita spending (based on the World

Bank’s Global Consumption Database). Only a few countries

on the continent have a notable proportion of households that

spend more than US$8.44 per day; in fact, this proportion

is above 10% of all households in only eight countries.

And, of these eight countries, only South Africa has a large

population. Furthermore, in 29 of the 36 countries in this

sample, more than half of all households have spending per

capita of less than US$2.97 per day. In most countries, the

focus for investors will therefore be the FMCG segment,

as most people are not able to afford durable or luxury

goods. That said, even though the proportion of middle- to

high-income groups is generally low, some of the more

populous countries will still have a reasonably large middle

class in absolute terms. In particular, there are bound to be

opportunities in some of the well-off suburbs of the financial

capitals of some countries, including Lagos and Nairobi.

Breakdown of African Income Groups & Estimating the Size of

the Middle Class

The above definition is probably too wide for a middle class,

though, and therefore the number of people that earn more

than US$8.44 per day is also estimated. Based on this

‘narrower definition’ of the middle class, Africa has 36.2

million people in the middle class, 48% of which reside in

South Africa. According to these estimates only five other

SSA countries have more than a million people in the middle

class. These are Ethiopia, Kenya, Ghana, Ivory Coast, and

Uganda. One of the most notable results is that Nigeria’s

middle class is relatively small, at only 803,200 people.

It is possible that the data underestimates Nigeria’s middle

class due to the small sample size; however, the result

stands to reason considering World Bank poverty statistics

that show that around 70% of Nigerians still live on less

than US$1.25 per day.

Although having relatively small middle classes in absolute

terms (400,000 people), there is a relatively large proportion

of middle class people in Gabon (28.2% of households) and

Mauritius (32.5% of households). Mauritius also benefits

significantly from the steady influx of tourists, who are

generally well-off and boost the demand for some products,

such as souvenirs and clothing. As such, developments like

the Bagatelle Mall south of Port Louis, Sunset Boulevard in

Grand Bay and Le Caudan Waterfront in Port Louis continue

to attract a constant flow of people. All countries in the

graph up to Chad have middle classes of more than 300,000

people, thus providing at least some opportunity for retail

companies looking to sell more than just the basic products.

11 | The African Consumer and Retail The African Consumer and Retail | 12

In a survey done by Nielsen in seven African countries,

namely Ethiopia, DRC, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda, and

Zambia, the affordability of brands was found to be the most

important factor in influencing consumers’ decision to buy,

picked by 37% of respondents. Brand loyalty also plays a big

role, with 31% of respondents saying they always buy the

same brand. (The survey is based on face-to-face interviews

with 5,000 urban and peri-urban residents between the ages

of 15 and 45 across income groups.) Some interesting results

from the survey are listed below:

• Of the seven countries, Ethiopia has the lowest per capita

spending on consumer packaged goods (CPG), Nigeria’s

nominal spending on these products is the largest, while

Tanzania has the largest number of CPG categories with a

penetration rate of higher than 75%.

• Zambia has the lowest TV penetration (67% compared to

an average of 90%), while the DRC has the lowest usage

of print media.

• Kenya has the highest penetration of modern retail

channels.

The fact that Africa’s population is a lot younger than the rest

of the world is an important point for retailers to consider.

According to the UN Population Division, the proportion of

Africans under the age of 25 is projected at around 55.5% in

2015, compared to 37.8% in South America, 36.6% in Asia,

29.1% in Northern America, and 23.9% in Europe. These

young people have significantly different tastes, preferences,

and aspirations than older generations, and this would be

reflected in their demand for different products.

Another important trend to consider is the rise of female

buying power. With more and more women earning their

own money (and with fertility rates declining), this is an

important expanding market for retailers to explore. The

reduction in fertility rates results in an increase in time spent

on other activities, as well as in an increase in the available

discretionary income. With more women having careers,

the importance of convenience with regard to the shopping

experience has also come to the fore, which might help the

development of formal retail in Africa. “The rising middle

class has meant that convenience has become important

for modern time-stripped consumers, with women in Africa

enjoying the mall culture, while wanting instant access to

information and technology and staying connected via

social networking and mobile phone technology”, according

to Daphne Kasriel-Alexander, consumers editor at

Euromonitor International.

Consumer Traits

CHALLENGES

The lack of physical infrastructure has been one of the main

constraints to the entry of formal retailers, as there are simply

not enough shopping centres available at present, while

bureaucratic obstacles and land issues further complicate

matters. For example, according to the UACN Property

Development Company in Nigeria, Lagos had only three

international standard-sized malls (of at least 20,000 m2) as

of October 2013, and could easily hold 20 - 25 malls owing to

its large population.

The ability to source products locally is an important factor

for retailers. Since most African countries lack an established

manufacturing base, they are often forced to source goods

from overseas, which increase their costs (through high

transport costs and import tariffs), while also making

supplies less reliable. To make matters worse, poor transport

infrastructure makes supplies even more unreliable: not

only is road infrastructure very poor across Africa, but there

are often bottlenecks at harbours for imported goods. The

accompanying graph shows the quantity and quality of local

suppliers, based on surveys by the World Economic Forum

(WEF). (The scores in the graph are an average of the ‘local

supplier quantity’ and local supplier quality’ sub-indices of

the WEF’s Global Competitiveness Index). Kenya performs

remarkably well, especially in terms of the quantity of local

suppliers where it is ranked 19th in the world. However,

only five countries in Africa are in the top half of the global

rankings and most African countries score very poorly on

this indicator. Angolan companies in particular seem to have

extreme difficulty sourcing products locally. Prospective

investors therefore have to take exceptional care to secure

reliable suppliers before entering the market across the

continent. Thorough research of the logistical and distribution

channels will also be needed, given the poor quality of

infrastructure.

Another major problem in many African countries are high

import tariffs. Since it is difficult to source local products,

African countries often rely on imports for a wide range of

goods. However, if import tariffs are high, it implies that

retailers need to ask high prices for them to sell goods

profitably. In some instances, this will lead to traders

smuggling goods via informal channels to avoid taxes.

In Maputo, Mozambique, for instance, informal traders

smuggle goods from South Africa, which enables them to

sell their products for up to three times less than formal

retailers, thereby making it difficult for retail companies to

compete with informal traders on imported goods.

Based on the trade freedom category of the Heritage Foundation’s

Index of Economic Freedom, Africa (and SSA in particular) lags the rest

of the world in terms of trade freedom. As can be expected, though,

there are intraregional differences, with Mauritius enjoying a very high

degree of trade freedom (ranked ninth out of 181 countries globally)

and Rwanda performing fairly well (ranked 68th), but most other

countries ranked outside the global top 100. In the accompanying graph

(‘Trading Across Borders’) African countries’ rankings in the Heritage

Foundation’s Trade Freedom and the World Bank’s Trading Across

Borders Indices have been combined.

13 | The African Consumer and Retail The African Consumer and Retail | 17

CHALLENGES

15 | The African Consumer and Retail The African Consumer and Retail | 16

RETAIL MARKETS IN A

SELECTION OF KEY AFRICAN

ECONOMIES

Africa’s retail sector remains relatively under-developed

at present, with most shopping being done at traditional

shops. Much has been said about the prospect for consumer

spending in Africa, driven by demographics and rapid

economic growth. This has fuelled massive interest from

international retailers to establish a footprint on the continent.

Given that many Africans tend to be brand-loyal, it is important

to enter the market at a relatively early stage, in order to have

first-mover advantage and to establish brand loyalty. Five

underlying trends are expected to boost Africa’s retail sector

over the long term, namely:

• Robust economic growth relative to the rest of the world;

• Still-low penetration rates of most consumer goods;

• Saturation levels and lack of further growth in mature

markets;

• The expansion of modern retail outlets, and the general

improvement in infrastructure; and

• A shift in the preferences of African consumers from

informal shopping outlets to modern formal Western-style

retail.

An increasing number of consumers are on the cusp of

the US$1,000 annual income level, which will allow for the

expansion of consumption beyond just the basics. Retailers

will be looking to take advantage of the large market at the

low end, while gradually starting to offer these consumers

higher-value products. In essence, the key strategy for most

retailers focussed on Africa will be to 1) capture the large

low-end market, and 2) benefit from higher margins as these

consumers start trading up, e.g. from unbranded to branded

beer. By establishing brand loyalty at an early stage, consumer

goods companies can benefit from the growth of the African

consumer. This is not to say that there is not potential for the

luxury goods sector as well, although it remains in its infancy at

present in most countries.

Using our demographic and economic potential indices as a

guideline, but also taking other factors into account (including

the current level of formal retail, penetration rates of consumer

goods, the prospect for policy reforms, and the potential for

regional expansion), we have identified five countries that

we believe show the biggest promise for retail development

over the long term. These countries are Egypt, Ghana, Kenya,

Morocco, and Nigeria. Since our 2014 report, Algeria has been

excluded – despite a relatively poor showing in the Consumer

Demand Potential Index, the country was included in the

previous report due to its strong demographic potential, which

implies that if economic policies improve, the retail sector

could truly prosper. However, due to the country’s dependence

on hydrocarbons, the recent drop in oil prices has weakened its

economic prospects. Algeria has therefore been replaced with

Egypt, which has excellent long-term retail prospects due to

its large, young population, and high population density along

the Nile. The economy is also gradually recovering from the

political turmoil of the past four years, with economic growth

subsequently expected to increase.

Traditionally, Egypt is a nation of street retailers, with most

Egyptians shopping in local neighbourhoods and at classic

souks such as Cairo’s Khan el-Khalili. The country’s retail

sector has been struggling since 2011 due to the uprising

and subsequent political turbulence. Furthermore, high

inflation has been the norm in recent years and has eroded

consumer purchasing power, forcing consumers to cut

costs and shop for second hand goods. On the upside,

political stability has returned after the 2014 election,

with the government committed to promoting economic

prosperity. According to Euromonitor, retail (especially in the

grocery industry) saw a slight improvement in 2014 because

consumers tended to prioritise the purchase of essentials

when their incomes were hit hard by inflation.

Western style malls were introduced to the country around

a decade ago with the opening of the Maadi City Centre

and City Stars. More projects such as the Mall of Arabia and

Cairo Festival City followed, but the political upheaval of

recent years slowed further progress. Post-2014 optimism

has seen major retail pioneers, such as Majid Al Futtaim,

announcing that it plans to expand its investments in Egypt

by about E£18bn (US$2.4bn) over the next five years. The

new developments include the 455,500 m2 Mall of Egypt,

which is to be located in Sixth of October City. Mall of Egypt

will be host to 420 stores and will include Ski Egypt, the first

indoor ski slope on the continent of Africa. Other, notable

new mall projects include the expansion of the City Centre

Alexandria by another 12,000 m2.

Despite, the growing optimism toward Egypt as an

investment destination, many malls have vacancy rates

of 25% and higher due to retailers remaining wary of the

country’s political environment.

This phenomenon should abate as longer periods of political

stability are experienced, which would create an opportunity-

rich environment for retailers wishing to set up shop in

future.

As is the case with many of its African peers, e-commerce

is showing great potential in the Egyptian retail market.

Egypt is one of Africa’s most advanced markets in terms

of internet penetration, with internet users numbering half

of the adult population in the country, and still growing.

The major online retailer, Jumia, has recently established is

first retail hub in Giza in order to capitalise on the growing

number on online shoppers in the North African nation.

Outlook – Retailing in Egypt is expected to see a recovery

over the coming years, supported by a wide array of factors.

These include greater political stability, stronger economic

growth and a rising level of disposable incomes. Sales

growth in both the food and non-food retail sectors should

benefit from increased urbanisation, a youthful population

and widening internet access in the North African country.

As investment in Egypt’s formal retail industry improve, so

more people should move towards modern retailing spaces

as opposed to the conventional market or neighbourhood

retailer. Furthermore, according to yStats, online shopper

penetration in Egypt is less than 10% at present, which

means that massive potential exists in this market especially

as the stable political environment persists. Since Egypt

still has around 25.2% of individuals living below the US$2

per day (2011 dollars) poverty line, and due to higher

inflation as well as high unemployment rates, the food and

lower-end of the clothing retail sector will dominate over the

medium term.

Positives: Youthful population; emergent middle class; continued urbanisation

Sectors: FMCG; clothing; luxury goods

Risks: Purchasing power of consumers under pressure at present due to high inflation; threat of terror attacks by jihadist

groups on shopping malls; low economic growth; high unemployment

Egypt

17 | The African Consumer and Retail The African Consumer and Retail | 18

Ghana’s modern retail sector is restricted mainly to Accra, with

some recent activity in Kumasi. In addition, most Ghanaians

still do their weekly shopping at street markets as the middle

class, who typically frequent modern shopping malls, is

still small. Although there are currently only a small number

of international retailers on the scene, the comparatively

accommodative business environment makes the West

African country more attractive as an investment destination.

Ghana was ranked 70th out of 189 countries in the 2015 World

Bank Doing Business survey. Only three countries in Africa

are ranked higher than Ghana: Mauritius (28th), South Africa

(43rd), and Rwanda (46th). It is also less of a problem to source

products in Ghana than it is in some other African countries.

Companies that have set up manufacturing facilities in the

country include Unilever, PZ Cussons, and Denmark’s Fan Milk

Group. Retailers can therefore buy a variety of products locally

rather than import them.

The West Hills Mall (27,000 m2) on the Accra-Cape Coast

Highway, the largest of its kind in Ghana, opened its doors

for business on 30 October 2014. The new development

boasts two anchor tenants, Shoprite and Palace, as well as

63 line shops. The success of this mall, which has a 100%

occupancy rate, has also spurred the developers of the first

phase, Delico Investments, to draw up plans for additions

to the mall, which will add 12,154 m2 of retail space to the

facility. The success of developments such as the West Hills

Mall, Accra Mall (22,900 m2), A&C Square Mall (10,000 m2)

and the Oxford Street Mall (6,230 m2) have prompted further

development plans, with Broll Property Group projecting in

its 2014 annual report that more than 165,000 m2 of formal

retail space will come into operation by the end of 2016. The

rapidly growing demand for shopping options is outpacing

the supply of viable modern shopping spaces in the West

African nation, where retail rents have pushed to levels as

high as US$60/m2, according to Broll property. Other notable

new developments include the Achimota Mall (13,000 m2)

and the Kumasi City Mall (27,000 m2).

A number of South African retailers have expressed a desire

to expand their presence in Ghana, and to take up space in

new developments. These include Shoprite, Game, Foschini,

Mr Price, Spur, Truworths, Woolworths, Edgars, Famous

Brands and Pick and Pay. Well-known international retailers

have been more reluctant to enter the market, although Zara,

Mango, Hugo Boss, Tommy Hilfiger, and TM Lewin have

recently shown interest.

Investors, developers and retailers are also monitoring a

number of key risks such as the depreciating cedi, high

inflation, the recent slowdown in economic growth, the

government’s large fiscal deficit and the erratic electricity

supply. Some of these issues are however being addressed:

most notably, the recent start-up of the Atuabo gas

processing plant will boost Ghana’s electricity-generating

ability and the signing of an economic reform programme

with the IMF will help to reduce the budget deficit over the

medium term, which in turn would also reduce inflation.

This will however take a few years to start having a positive

impact on the Ghanaian economy, with consumers likely

to feel the pinch of a more austere budget (lower wage

increases in particular) in the interim.

Outlook – Formal retail space in Ghana is in short supply on

the back of increased latent demand from consumers, which

has been boosted over the past decade by strong levels of

economic growth, albeit slower in recent months. However,

consumers are currently under pressure due to high levels

of inflation, a rapidly depreciating currency, high commercial

bank interest rates, and higher utility and fuel prices. Private

consumption levels will therefore be negatively impacted

during the coming year, but we remain upbeat about the

long-term potential for the sector, which will be supported

by a growing middle class and a declining population growth

rate. E-commerce should also pick up in Ghana as around

five million (almost 20% of the population) internet users

are currently active. There is massive potential in this

market as stronger future growth prospects should be

accompanied by a higher number of internet users with

greater disposable incomes.

Positives: Opportunity to benefit from first demographic dividend; generally accommodating business environment;

popularity of shopping centres

Sectors: FMCG; clothing; electronics; appliances

Risks: Purchasing power of consumers under pressure at present due to high inflation and depreciating currency; risk of

higher taxes due to the government’s weak finances

Ghana

Kenya has a well-developed retail sector in an African

context, with formal retail market penetration rates at 25%

- 30%, double that of Nigeria. The country boasts a growing

and sizeable emerging middle class with the New World

Wealth report for 2014 reporting that per capita wealth in

Kenya has grown by 89% since 2000. The average value of

a shopper’s basket has risen by 67% in five years, which

makes Kenya the continent’s fastest growing retail market.

BMI estimates that per capita food consumption will increase

by 4.2% p.a. over the 2014-19 period in local currency terms.

In absolute terms, Kenyans are generally still poor, though. In

fact, according to the World Bank, around 45.9% of Kenyans

live on less than US$2 (2005 dollars) a day. As the poor

typically spend a greater portion of their income on food, the

Kenyan retail market is forecast to be dominated by the food

market over the medium term.

The East African nation’s grocery retail market has been

monopolised by local supermarket chains such as Nakamutt

(34 stores), Tuskys (45 stores), Uchumi (22 stores) and

Naivas (29 stores), with foreign chains struggling to make

inroads due to a general resistance to foreign takeovers.

Foreign investors looking to get exposure to Kenya’s retail

play has therefore been limited to purchasing shares in

Uchumi, the only listed Kenyan retailer. Despite this, the

French supermarket giant Carrefour is opening two new

grocery stores in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, by the end of

2015. Other notable, foreign retail establishments that have

recently made a move on the Kenyan market are the US

brands Domino’s Pizza, Cold Stone Creamery and KFC in

Nairobi and Mombasa.

As in the case of countries such as Nigeria, e-commerce has

also grown significantly in the Kenyan retail and wholesale

market. Kenya is one of the most technologically advanced

nations in Africa when it comes to mobile money payments.

Nearly 26 million Kenyans make use of mobile money, which

represents more than half the adult population. The East

African nation’s openness to new technology has made it

a rich source of business for Amazon-style online shopping

sites like Jumia and Kilimall. The online shopping market will

continue to present a lucrative investment opportunity in

Kenya as the number of mobile internet users will continue to

grow in the near future.

Outlook – Continued strong growth is predicted for Kenya’s

retail sector, supported by an on-going shift to formal retail,

growing levels of urbanisation, and a rising middle class.

Retailers are expected to remain innovative in order to hold

on to market shares. For example, online shopping sites are

creating user incentive schemes to lure a larger number of

clients. The strong expansion of formal financial services

to the previously unbanked in Kenya – through mobile and

agency banking – has opened up an important opportunity

to attract new customers, especially through e-commerce.

Kenyan retailers are expected to increase the range of their

product offerings further over the outlook period in order to

build market share. Further potential also lies in the upper

end of the retail market as the number wealthy Kenyans is

forecast to grow by 73% by 2023, according to the 2014

New World Wealth report. Kenya also has the fourth-highest

number of high-net-worth individuals in Africa.

Positives: Strong population growth; growing middle class; educated labour force; dynamic private sector; regional leader –

possibilities for regional expansion

Sectors: FMCG; clothing; personal care products

Risks: Risk of terror attacks by Al Shabaab; private consumption dependent on agricultural earnings; risk of inflation and higher

taxes; exposure to Europe for export and tourism revenues

Kenya

Morocco is another African nation that shows promise in

the retail sector. New patterns of trade, such as the shift

from traditional grocery retailers to modern super and

hypermarkets, are emerging in the North African country.

Mobile retailing is also on the rise, owing to greater internet

connectivity and a higher number of individuals who have

become banked. Moreover, we estimate that Morocco falls

amongst the top 10 countries in terms of dollar millionaire

growth (26% p.a.) over the 2007-13 period, making its

luxury brand market ripe for the picking.

According to Euromonitor, the Moroccan department of

Trade and Industry implemented the Plan Rawaj (for 2020)

to develop modern retail spaces in a nation where the

modern mall has not been particularly successful. Amongst

the legislative reforms are amendments to a 1955

commercial property law which previously made landlords

reluctant to lease retail space, since tenant eviction was

very difficult. Four new mall developments, under the

auspices of this plan, have occurred since 2011 with the

Carre Eden Mall (27,000 m2) in Marrakech being the most

recent. One of the exciting new retail developments in

Morocco will be the construction of the 540-metre Al-Noor

tower in Casablanca. This 114 storey building, which will

be built by Dubai-based Middle East Development LLC,

will be the tallest building in Africa, housing a seven star

hotel, a business centre and a shopping mall.

The Moroccan grocery retail sector continues to be d

ominated by local players such as Marjane Holdings (33

hypermarkets). The other notable market players in the

grocery arena are Label’Vie , Hyper SA, and Ynna holdings.

National brands typically benefit from their long existence

in Morocco as well as their extensive knowledge of the

North African nation’s retail market. Historically, Moroccan

brands, due to their market experience, have also tailored

their offerings to the purchasing power of social groups

within the country, giving them a competitive edge.

Furthermore, e-commerce is experiencing a boom in the

North African country, with online shopping behemoth,

Jumia, and other internet retail sites such as Hmizate and

Shoppeos having already established themselves in the

market. Much business potential can be unlocked in this

industry since Morocco’s internet usage is high and rising,

according to the Agence Nationale de Reglimentation des

Telecommunications (ANRT). The growth in the North African

country’s e-commerce retail industry could have been even

greater if more attention was paid to Arabic translations of

online retail platforms, greater promotions on social media

occurred and focus was placed on fast growing mobile

device usage.

Outlook – The overall outlook for Morocco’s retail sector

is positive and growth will continue to be supported by a

growing urban middle class. The shift from traditional grocery

retailers to modern hyper and supermarkets will continue

strongly especially as the large grocery chains such as

Label’vie and Marjane continue to open outlets in second

and third tier cities. Moreover, the tourism industry should

contribute to the growth in general retail as tourist arrivals in

Morocco are expected to surpass 11 million per year by 2016.

The upper middle and high earning income groups present

interesting opportunities for retail due to their demand for

brand names and quality products. Speciality retailers

remain a novelty in Morocco and, given the low number of

cars per capita, vehicle retail also presents significant

growth opportunities.

Positives: Rising urbanisation; favourable age structure;

growing middle class

Sectors: FMCG; clothing; vehicles; luxury goods

Risks: Notable exposure to Europe could negatively affect

consumer spending power

Morocco

19 | The African Consumer and Retail The African Consumer and Retail | 20

21 | The African Consumer and Retail The African Consumer and Retail | 22

Although Nigeria has experienced high real GDP growth

over the past decade, a large share of the growth in income

has gone to a small, well-connected group (often political

elites) benefiting from oil rents. Consumer goods companies

catering to the lower and middle classes have therefore not

benefited from high oil prices as much as one would have

expected. The recent sharp decline in the international oil

prices is therefore expected to have more of an impact on

the rich than the poor. Still, the recent devaluations of the

naira will increase the cost of imports and thereby weigh on

consumers’ purchasing power. Moreover, tighter monetary

policy due to capital flight and a weaker currency has also

impeded access to credit. These negative trends will abate

over the medium term and should not derail Nigerian

economic prosperity over the long run.

Despite these problems, the Nigerian wholesale and retail

industry (which accounts for 16.4% of GDP) remains a

lucrative investment opportunity on the back of a large and

rising population and an increased rate of urbanisation.

The retail market in the West African country has become

somewhat more sophisticated from its relatively informal

origins prior to 2000. The first modern mall developments in

the country were the Ceddi Mall in Abuja and the Palms Mall

in Lekki, Lagos. The consequent success of these projects

due to the voracious appetite of the up and coming middle

class has led to further developments such as the Palms Polo

Park Mall in Enugu, the Palms Ilorin in Kwara, as well as the

Adeniran Ogunsanya Mall in Surulere and Ikeja City Mall in

Lagos. Retail space in the country has therefore grown from

an initial 30,000 m2 to 227,000 m2.

The geographical spread of malls has increased over

time as well. In 2006, only two Nigerian cities had malls,

whereas there now are 10 cities that have functioning

malls. In addition to Abuja and Lagos, Port Harcourt, Ibadan,

Enugu and Delta now boast modern shopping complexes.

Greenfield Assets Limited and the Abia State government

are currently developing the first purpose built Smart Mall in

the world and the largest mall in Africa in the city of Osisioma

Ngwa. This mall will have an impressive 280,000 m2 retail

space, which roughly translates into 5,830 shops. In addition,

the development will comprise a games arcade, petrol

stations, climate-controlled warehouse and state of the

art cinemas.

The initial retail landscape was dominated by Nigerian and

South African firms. Amongst the major South African players

in the West African nation are Game, Nandos, Shoprite, Mr

Price, Foschini and Barcelos. Recently, the country has also

seen an influx of Middle Eastern, American and European

brands such as Swatch. Brand diversity remains limited in

many of the newly-developed malls and holds great potential

for new business ventures in Africa’s largest and most

populous economy.

Nigeria has also seen the development of a market for luxury

goods. The country’s burgeoning middle class is expected

to have consumer spending in excess of US$25bn by 2020.

This is comparable to spending in Mumbai, India’s largest

business hub. Furthermore, the West African nation’s

demand for champagne is expected to more than double

between 2011 and 2016. Nigeria is also the world’s fastest

growing aviation market, with 70 new private jets projected

to be delivered in the country over the next four years.

However, according to the World Bank, in 2010 about 46%

of Nigerians lived on US$2 or less a day (at 2010 international

prices). These stark contrasts further give credence to the

fact that the Nigerian retail and wholesale market is

highly polarised.

The e-commerce trend also shows no abatement. Major

internet sites such as Jumia and Konga have done well in the

fashion and mobile devices markets, whereas Supermart.ng

and Gloo.ng have made inroads in the order and delivery of

supermarket goods. According to Disrupt Africa, the Gloo.ng

site had around 7,000 users per month at the start of 2015,

up 800% y-o-y. The formal supermarket landscape remains

highly fragmented as a population of 180 million people are

serviced by only two supermarket chains with 15 outlets

countrywide. Should the problems in infrastructure and the

difficult business environment receive more attention from

Nigerian authorities, both the off and online grocery shopping

markets have massive investor potential.

Positives: Large market size; youthful population; urbanisation; privatisation of power sector

Sectors: FMCG; clothing; luxury goods

Risks: Risk of naira devaluation, which would raise cost of imported goods; poor infrastructure; difficulty

to source products due to small local manufacturing sector; political risk; security risks in northern states

Nigeria

Despite the wealth of opportunities in the Nigerian retail

and wholesale market, certain challenges in the business

environment make investment difficult. The West African

nation is dominated by both high financing costs and very

high construction prices. Infrastructure gaps also inhibit

the development of effective retail supply chains. Security

concerns like the rising insurgency trend especially in the

north, also have a major disruptive impact on the business

environment. International investors also seem to have

misconceived notions about Nigeria such as the absence of a

market for luxury goods.

Outlook – The Nigerian consumer may well be under

pressure over the next few years as low oil prices put

pressure on the Naira and government infrastructure

spending plans. However, the retail sector remains an

attractive prospect over the longer term. Informal retail

channels will continue to dominate. This is despite some

specific measures being implemented by State governments

to encourage the formalisation of the sector. The share of

modern retail is however expected to continue increasing

over the coming years, driven by the development of a

number of large-scale modern shopping centres. The

low-income consumer by far dominates the Nigerian retail

scene, which will provide a lot of opportunities for FMCG

companies. In addition, online grocery shopping is becoming

ever more popular due to the limited access to formal grocery

supermarkets. Brand diversification will also present a good

investment opportunity in the future as average household

incomes grow. Despite Nigeria’s rich investment potential,

some serious challenges for retailers to set up shop persist.

If the country’s infrastructure deficiencies and cumbersome

legislative hurdles are not addressed in the near future,

the cost of establishment for international brands may

remain too high.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION

Actis

African Development Bank

Citi Group

Disrupt Africa

Economist Intelligence Unit

Euromonitor International

Financial Times

Food and Agriculture Organisation

Heritage Foundation

How we made it in Africa

International Monetary Fund

NKC African Economics

Oxford Business Group

Trade Map

UACN Property Development

UN Population Division

World Bank

World Economic Forum

World Wealth Report

yStats

The African Consumer and Retail | 24

CONTACT DETAILS

© 2016 KPMG Africa Limited, a Cayman Islands company and a member firm of the KPMG

network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG

International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. The KPMG name, logo and “cutting through

complexity” are registered trademarks or trademarks of KPMG International. MC14857.

kpmg.com/social media

kpmg.com/app

Seyi Bickersteth

Chairman KPMG Africa

T: +23412805984

E: seyi.bickersteth@ng.kpmg.com

Bryan Leith

COO KPMG Africa

T: +27116476245

E: bryan.leith@kpmg.co.za

Benson Mwesigwa

Africa High Growth Markets

KPMG Africa

T: +27609621364

E: benson.mwesigwa@kpmg.co.za

Molabowale Adeyemo

Africa High Growth Markets

KPMG Africa

T: +27714417378

E: molabowale.adeyemo@kpmg.co.za

Wole Obayomi

Partner, Consumer markets

West Africa

T: +23412718932

E: wole.oba[email protected].com

Dean Wallace

Partner, Consumer markets

South Africa

T: +27116476960

Mohsin Begg

Manager, Consumer markets

South Africa

T: + 27827186841

Jacob Gathecha

Partner, Consumer markets

East Africa

T: +254202806000

E: jgathec[email protected]

Fernando Mascarenhas

Partner, Consumer markets

Angola

T: +244227280102

E: femascarenhas@kpmg.com

KPMG Africa