i

SUMMARY

This document analyzes the funding mechanism of employer-sponsored health

benefit plans that filed a Form 5500 Annual Return/Report of Employee Benefit Plans

(“Form 5500”). It compares fully insured, mixed-funded, and self-insured health

plans for reporting periods that ended in 2016, and presents select historical series

for the years 2007 through 2016. For a subset of health plan sponsors, publicly

available corporate financial data were also used. The primary findings include:

Just under one-half of Form 5500 filing health plans (49%) were self-insured

or mixed-funded (funded through a mixture of insurance and self-insurance)

in 2016, and those plans covered 82% of plan participants.

At the plan level, the shares of self-insured (42%), mixed-funded (7%), and

fully insured (51%) plans are very similar to those of 2015.

In 2016, self-insured plans covered 46% of plan participants, mixed-funded

plans 37%, and fully insured plans 18%. (Percentages do not sum to 100%

because of rounding.) These shares reflect a small decrease in self-insurance

relative to 2015, but that change may be due to a definitional issue.

As reported in Form 5500 filings, stop-loss coverage among self-insured plans

declined from 30% in 2007 to 26% in 2010, flattened out at approximately

that level until 2015, and resumed its decline to 25% in 2016. Stop-loss

coverage among mixed-funded plans also declined—from 24% in 2007 to

below 17% by 2014—but increased slightly in recent years. These

percentages likely underestimate the overall prevalence of stop-loss

insurance.

Most Form 5500 filing plans with fewer than 100 participants were self-

insured in 2016. This is most likely due to Form 5500 filing requirements

rather than being representative of all small plans.

Among Form 5500 filing plans with 100 or more participants, the prevalence

of self-insurance generally increased with plan size. For example, 30% of

plans with 100-199 participants were mixed-funded or self-insured in 2016,

compared with 91% of plans with 5,000 or more participants. This is similar

to 2015.

Mixed funding is found primarily among very large plans. For example, 2% of

plans with 100-199 participants were mixed-funded in 2016, compared with

43% of plans with 5,000 or more participants.

Self-insurance rates varied by industry, with utilities, mining, agriculture, and

construction firms having the highest prevalence of self-insurance.

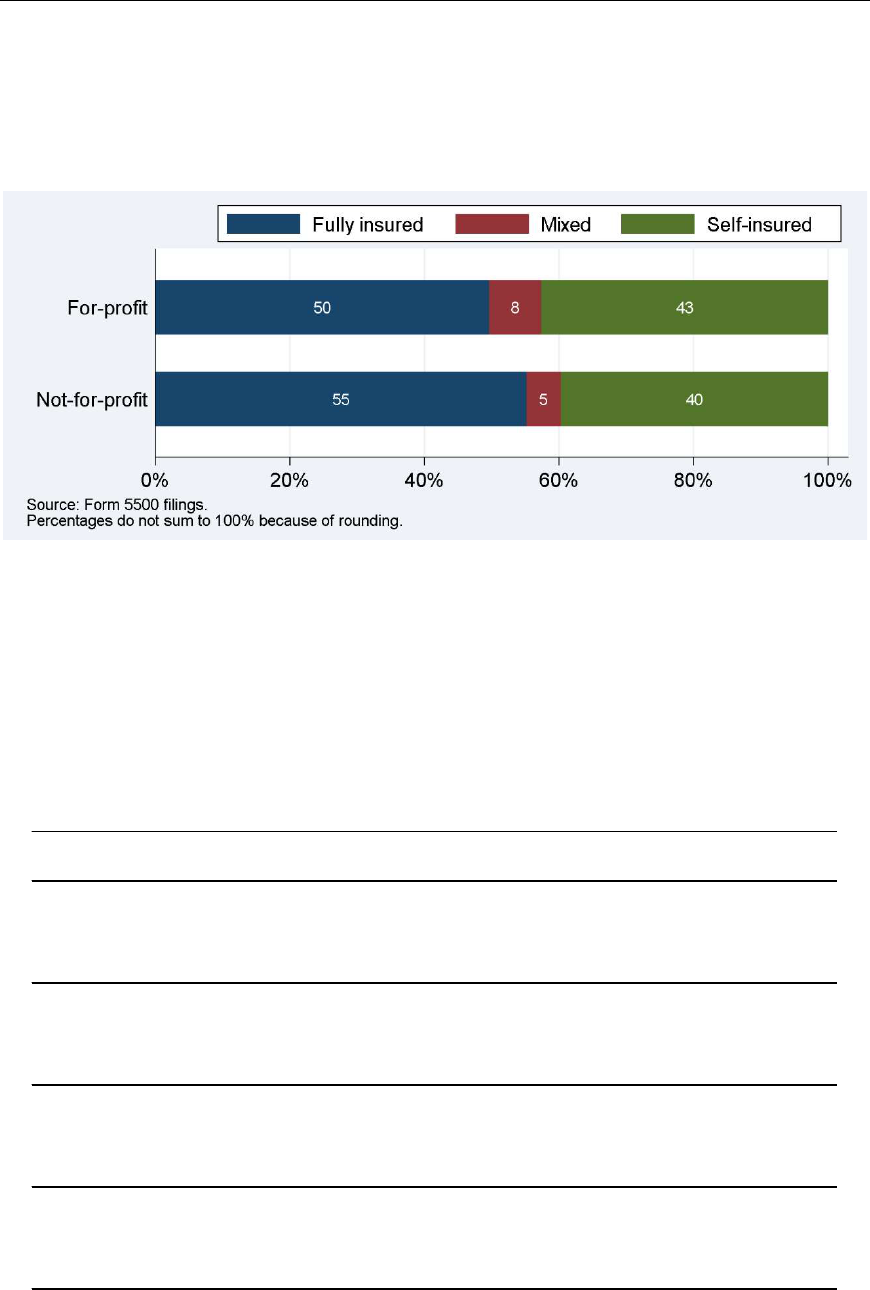

One-half (50%) of plans sponsored by for-profit organizations were self-

insured or mixed-funded, compared with 45% of plans sponsored by not-for-

profit organizations. Weighted by the number of participants, not-for-profit

organizations were much more likely to be self-insured and much less likely to

be mixed-funded than for-profit firms.

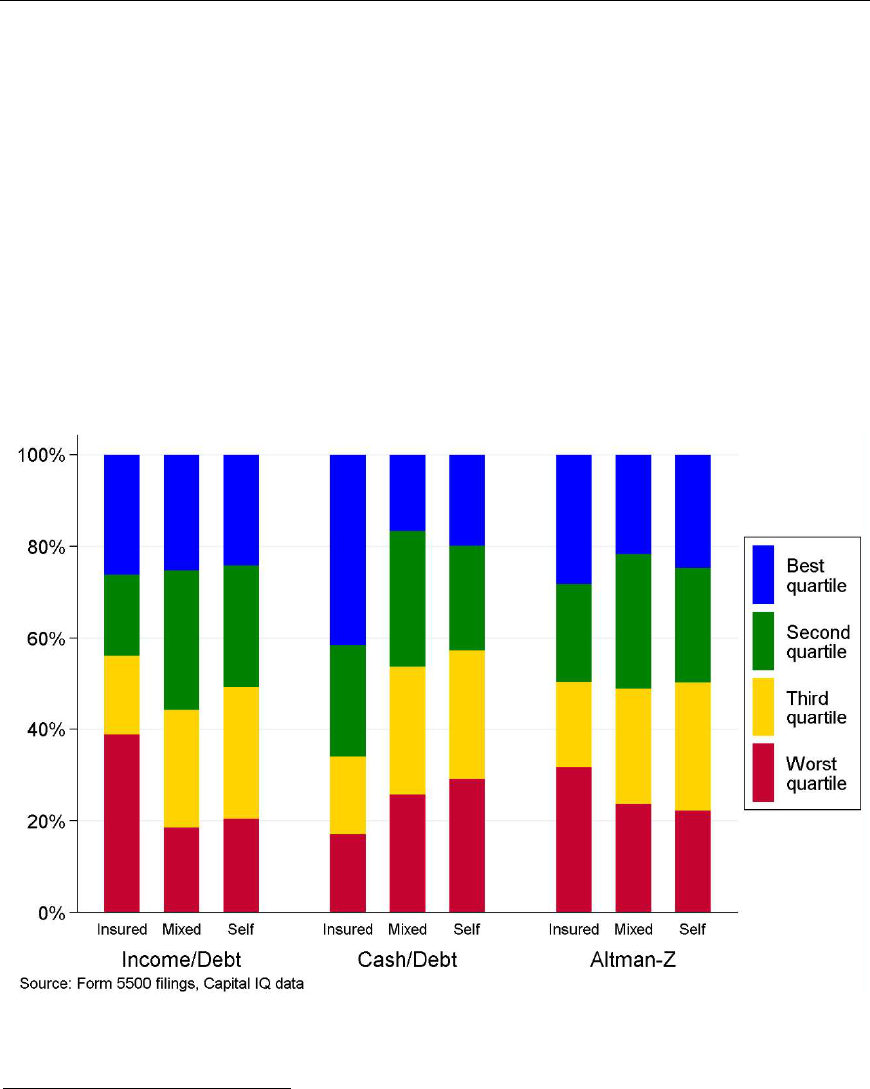

There is no consistent evidence that the financial health of fully insured plan

sponsors is better or worse than that of mixed-funded or self-insured

sponsors.

ii

CONTENTS

Summary........................................................................................................i

1. Introduction.............................................................................................1

2. Data Sources ............................................................................................2

Form 5500 Filings of Health Benefit Plans.......................................................2

Financial Information from IRS Form 990 and Capital IQ ..................................6

Matching Form 5500 Filings and Capital IQ Records .........................................8

3. The Definition of Self-Insurance ............................................................10

The Definition of Funding Mechanism Is Driven by Available Data.................... 10

Issues in Defining Funding Mechanism ......................................................... 12

Stop-Loss Insurance .................................................................................. 13

4. Analysis..................................................................................................14

Funding Mechanisms for Plans and Participants ............................................. 14

Funding Mechanisms by Plan Size................................................................ 15

Funding Mechanisms by Year ...................................................................... 17

Funding Mechanisms by Industry ................................................................ 19

Funding Mechanisms over the Life Cycle of Plans........................................... 20

Stop-Loss Coverage of Plans....................................................................... 30

Funding Mechanisms and Financial Metrics ................................................... 32

5. Conclusion..............................................................................................36

Technical Appendix .....................................................................................37

Disclaimer ...................................................................................................39

1

1. INTRODUCTION

The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) (§1253) mandates that

the Secretary of Labor prepare annual reports with general information on self-

insured group health plans (including plan type, number of participants, benefits

offered, funding arrangements, and benefit arrangements), as well as data from the

financial filings of self-insured employers (including information on assets, liabilities,

contributions, investments, and expenses). The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL)

engaged Advanced Analytical Consulting Group, Inc. (AACG) to assist with the ACA

mandate.

1

This document is intended to serve as an appendix to the Secretary’s

2018 Report to Congress.

As required by the ACA, the primary data source for this document is the information

provided to the DOL by health plan sponsors on Form 5500 Annual Return/Report of

Employee Benefit Plans (“Form 5500”) filings. For a subset of health plan sponsors,

publicly available corporate financial data were also used.

The current report analyzes Form 5500 filings for plan years that ended in 2007-

2016, i.e., several years before and after the enactment of the ACA in March 2010.

The primary findings for 2016 are similar to those for 2015, with a couple of

noteworthy updates: while self-insurance among plans generally decreased in recent

years, the slight increase first documented in last year’s report continued in 2016.

Weighted by plan participants, self-insurance halted its long-term increase, though

this may be due to a definitional issue (see footnote 23, page 17 for further

discussion).

The general approach and algorithm to determine funding mechanism are unchanged

from those in last year’s report.

Section 2 of this report describes Form 5500 and other data sources, including data

quality, consistency issues, and the extent to which financial data were matched to

health plan filings. Section 3 defines funding mechanism as used in this report.

Section 4 presents the results of our data analysis, and Section 5 concludes.

The views, opinions, and/or findings contained in this report should not be construed

as an official Government position, policy or decision, unless so designated by other

documentation issued by the appropriate governmental authority.

1

Deloitte Financial Advisory Services LLP (“Deloitte”) served as a subcontractor to

AACG in preparing the 2015-2019 iterations of this report. Conversely, AACG served

as a subcontractor to Deloitte for the 2011-2014 reports.

2

2. DATA SOURCES

The quantitative analysis in this report is based on three data sources: Form 5500

group health plan filings, Internal Revenue Service Form 990 Return of Organization

Exempt From Income Tax (“Form 990”) filings, and annual financial reports. This

section discusses the data sources and the algorithms to match the three sources.

Form 5500 Filings of Health Benefit Plans

The Form 5500 Series was developed to assist employee benefit plans in satisfying

annual reporting requirements under Title I and Title IV of the Employee Retirement

Income Security Act (ERISA) and under the Internal Revenue Code. The Form 5500,

including required schedules and attachments, collects information concerning the

operation, funding, assets, and investments of pensions and other employee benefit

plans. It is generally due, unless extended, by the last day of the seventh month

after the plan year ends (2016 Instructions for Form 5500).

ERISA requires any administrator or sponsor of an employee benefit plan subject to

ERISA to annually report details on such plans unless exempt from filing pursuant to

regulations issued by the DOL. Welfare plans with fewer than 100 participants

(“small plans”) are generally exempt, except if they operate a trust or are a plan

Multiple Employer Welfare Arrangement (MEWA). As a result, small welfare plans

that do not need to file a Form 5500 are not covered by the analysis in this report.

2

Also, non-ERISA plans, such as governmental plans and church plans, do not need to

file a Form 5500 and are not covered by the analysis in this report.

Benefits other than pensions are collectively referred to as welfare benefits.

Generally, separate Forms 5500 are filed for pension benefits and for welfare

benefits. This report centers on health benefits only, and is thus based on a subset of

welfare benefit filings.

3

The Form 5500 consists of a main Form 5500 and a number of schedules and

attachments, depending on the type of plan and its features. The main Form 5500

collects such general information as the name of the sponsoring employer, the type

of benefits provided (pension, health, disability, life insurance, etc.), the funding and

benefit arrangements, the effective date of the plan, and the number of plan

participants. If some or all plan benefits are provided through external insurance

contracts, Form 5500 plan filings must include one or more Schedules A with details

on each insurance contract (name of insurance company, type of benefit covered,

number of persons covered, expenses, etc.). If any assets of the plan are held in a

trust, a Schedule H or Schedule I must be attached with financial information.

Schedule H applies to plans with 100 or more participants, whereas smaller plans

may file the shorter Schedule I. Starting with the 2009 plan year, certain small plans

2

In 2016 the DOL estimated that 2,158,000 health plans cover fewer than 100

participants (Federal Register Vol. 81, July 21, 2016, page 47502). Our analysis

includes only 5,773 such plans (0.3%).

3

For the purpose of this report, only health benefits are relevant. However, 86% of

2016 Form 5500 health plan filings reported on both health and other types of

benefits (dental, vision, et cetera).

3

may file a Form 5500-SF (Short Form) with less detailed information.

4

This report’s

analysis includes 1,512 Form 5500-SF filings in 2016.

Some plans file a Form 5500 even though they are not required to do so. This report

excludes such voluntary filers from the analysis. Apart from this exclusion, our

analysis covers the universe (not a sample) of health plans that filed a Form 5500.

The analysis includes only one filing per year for plans that submitted multiple Form

5500 filings during a calendar year.

Table 1 presents the distribution of plan size, as measured by the number of

participants at the end of the reporting period, for filings in statistical year 2016, i.e.,

for filings with a reporting period that ended in 2016. Throughout this report,

participants may include active and retired employees, but will exclude dependents.

For 2016, the analysis is based on more than 56,000 plans that together covered

more than 75 million participants.

5

Table 1. Distribution of Health Plans and Health Plan Participants, by Plan

Participant Counts (2016)

Participants Participants

in p

lan

Plans Percent (millions) Percent

Zer

o

1,859 3.3% 0.0 0.0%

1-99 3,914 7.0% 0.2 0.2%

100-199 18,127 32.2% 2.6 3.5%

200-499 17,098 30.4% 5.3 7.1%

500-999 6,520 11.6% 4.5 6.0%

1,000-1,999 3,774 6.7% 5.3 7.1%

2,000-4,999 2,749 4.9% 8.5 11.3%

5,000+ 2,170 3.9% 48.7 64.8%

Tot

al

56,211 100.0% 75.2 100.0%

Source: Form 5500 health plan filings.

Not

e: Numbers may not sum to totals due to rounding.

4

To be eligible to use the Form 5500-SF, the plan must generally have fewer than

100 participants at the beginning of the plan year, meet the conditions for being

exempt from the requirement that the plan’s books and records be audited by an

independent qualified public accountant, have 100% of its assets invested in certain

secure investments with a readily determinable fair value, hold no employer

securities, not be a multiemployer plan, and not be required to file a Form M-1,

Report for Multiple Employer Welfare Arrangements (MEWAs) and Certain Entities

Claiming Exception (ECEs) for the plan year (2015 Instructions for Form 5500-SF).

5

The number of participants is based on the number reported in Form 5500 filings

and may overestimate the number of plan participants who receive health benefits. A

single Form 5500 filing may reflect multiple welfare benefit types/options available

under a single plan, and some participants may opt out of the health benefit option

but participate in a different welfare benefit option. For example, in a welfare plan

that provides multiple types of benefits, 500 employees may receive long-term

disability benefits while only 400 employees choose health benefits. The number of

plan participants reported on the Form 5500 would be 500.

4

As previously noted, health plans with fewer than 100 participants (small plans) are

generally not required to file a Form 5500 unless they hold assets in a trust. Small

plans in our analysis are thus a select subset of all small plans. In contrast, plans

with 100 or more participants (large plans) are generally required to file a Form

5500 unless otherwise exempt from filing, so we believe our analysis covers the vast

majority of large ERISA-covered plans in the United States.

Plans with fewer than 100 participants accounted for 10% of plans in our analysis.

6

Almost two-thirds of plans had between 100 and 499 participants. Most participants,

however, were in the largest plans. Plans with 5,000 or more participants make up

only 4% of all plans in our sample, but they account for 65% of all participants.

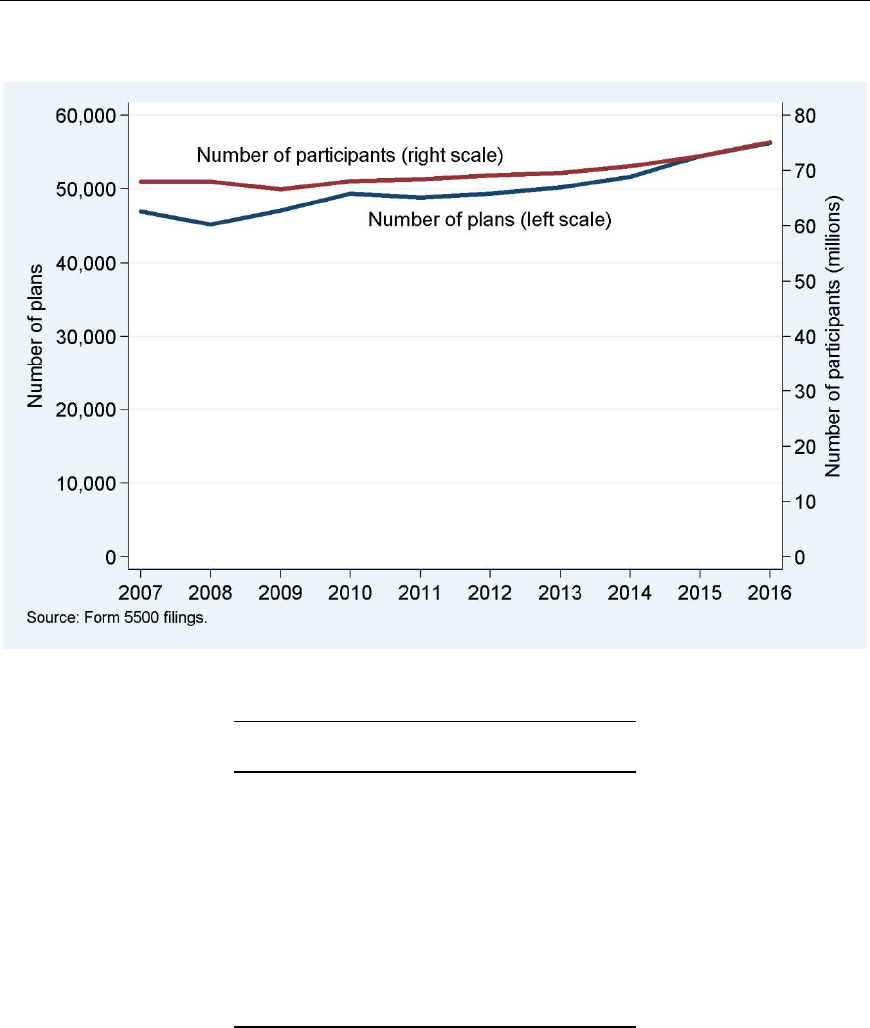

Our analysis covers statistical years 2007 through 2016. As shown in Figure 1 and its

underlying counts in Table 2, each statistical year includes between approximately

45,000 and 56,000 plans providing health benefits. The number of participants

ranged from approximately 63 million to 75 million per year. Between 2007 and

2016, the numbers of plans and plan participants have generally been increasing. An

exception was 2008, when the transition from paper to electronic filings may have

caused filings to be imperfectly captured.

7

The number of plans also decreased in

2011, shortly after the ACA was passed, but bounced back in 2012. The number of

plan participants did not drop in 2011, which could be consistent with plans that

terminated or otherwise ceased filing in 2011 being generally small, or the 2011

reduction in plan filings being in part due to plan mergers. Between 2015 and 2016,

the number of plans and participants grew by 3% to more than 56,000 and 75

million, respectively.

6

The filing exemption for plans with fewer than 100 participants that do not hold

assets in a trust is based on number of participants at the beginning of the year

(BOY), whereas Table 1 is based on end-of-year (EOY) participants. Some plans with

zero or 1-99 participants in Table 1 may be plans with more than 100 participants at

the beginning of the year and fewer than 100 (including zero) at the end of the year.

7

Prior to plan year 2009, Forms 5500 were generally filed on paper. Paper filings

were scanned and converted into an electronic database using a combination of

optical barcodes and optical character recognition. Starting with the 2009 plan year,

filers are required to file electronically using the ERISA Filing Acceptance System

(EFAST2).

5

Figure 1. Health Plans and Participants, by Statistical Year

Table 2. Health Plans and Participants, by Statistical Year

Statistic al Participants

year Plans (millions)

2007 46,936 68.0

2008 45,184 68.0

2009 47,104 66.6

2010 49,341 68.1

2011 48,855 68.4

2012 49,399 69.1

2013 50,227 69.6

2014 51,643 70.8

2015 54,488 72.6

2016 56,211 75.2

Source: Form 5500 health plan filings.

Table 3 shows the percentage of health plan filings that could be matched to their

corresponding filing in the previous year. While generally in the 83%-88% range,

this match rate was substantially lower in 2009, perhaps because of data capture

errors related to the then-new electronic filing requirement. In order to gauge

consistency in the reporting of the number of participants, the table also illustrates

to what extent participant counts of matched pairs of plans changed from one year

to the next. Table 3 shows that, at the median, plans reported approximately the

same size as in the prior year, suggesting that the matches are generally accurate

and that there is consistency in the reporting. Except in 2009, the distributions are

6

fairly stable over time and the interquartile range (the difference between the 75

th

and 25

th

percentiles) of plan size growth was about 15 percentage points.

Table 3. Distribution of Year-on-Year Participant Increases in Plans Matched

across Years

Number of Percentage

Statistical plans matched to a Year-on-year inc rease

year in year t plan in t-1 25th pct Median 75th pct

2007 46,936 84.8% -6.3% 0.8% 9.1%

2008 45,184 86.1% -7.7% 0.1% 8.2%

2009 47,104 79.7% -12.0% -2.1% 5.3%

2010 49,341 83.0% -8.6% -0.7% 6.1%

2011 48,855 87.8% -6.9% 0.0% 7.0%

2012 49,399 87.8% -5.8% 0.5% 8.1%

2013 50,227 87.5% -5.9% 0.5% 8.1%

2014 51,643 86.5% -5.6% 1.0% 9.1%

2015 54,488 84.6% -5.7% 1.3% 9.7%

2016 56,211 85.6% -6.1% 1.1% 9.5%

Source: Form 5

500 health plan filings.

Note: Match rates based on all Form 5500 health plan filings.

Participant increases based on the analysis sample only.

Financial Information from IRS Form 990 and Capital IQ

Several of our research questions seek to understand the relationship between a plan

sponsor’s financial health and the plan’s characteristics. To address these questions,

we matched Form 5500 health plan filings with two sources of financial information:

Form 990 and Capital IQ corporate financial data. We obtained plan sponsors’ not-

for-profit status from the Form 990 and some of their financial information from

Capital IQ. This section describes our approach and the number of Form 5500 filers

for which we achieved a statistical year 2016 match with the Form 990 or Capital IQ.

Not-for-Profit Status from Form 990

We determined whether health plan sponsors are for-profit or not-for-profit by

matching Form 5500 filings to Form 990 filings. We identify not-for-profit plan

sponsors by the existence of a Form 990 filing from the plan sponsor. Tax-exempt

organizations file a Form 990 annually with the IRS unless exempt from filing. The

IRS makes select fields of Form 990 filings, including Employer Identification

Numbers (EINs) and the organizations’ names, publicly available on its website. If

the corporate sponsor listed on a Form 5500 health plan filing was matched to a

Form 990 filing, and the entity that filed a Form 990 was not itself a benefit plan, we

identify the plan sponsor as a not-for-profit organization; otherwise, it is considered

for-profit.

8

8

Some welfare plans of for-profit corporations were themselves not-for-profit

entities. For example, the Form 5500 plan sponsor could be listed as XYZ

Corporation Employee Benefits Plan, a not-for-profit entity for which a Form 990 was

located. In such cases, we ignored the Form 990 entry for XYZ Corporation Employee

7

The match is carried out by EIN and organization name. To reduce mismatches due

to name spelling variations, we normalize names prior to matching, as discussed

below. The analysis sample for statistical year 2016 includes 56,211 filings of which

9,418 (17%) had sponsors that filed a Form 990 and were thus identified as not-for-

profit. They accounted for 15.2 million participants, or 20% of the total under study.

Financial Metrics from Capital IQ

Our financial metrics information comes from Capital IQ, a provider of financial and

other data for companies in the United States and elsewhere. Capital IQ culls Form

10-K filings and other sources to collect data on companies with public financial

statements, which generally includes companies with publicly-traded stock or bonds.

9

Our extract from its database contains information on the 2016 financial

performance for about 8,700 companies with public financial information whose

primary geographic location is in the United States.

We extracted fields that capture company characteristics, financial strength, financial

health, and financial size. In particular:

Market capitalization: total value of outstanding common stock as of the end

of the company’s financial reporting period;

Revenue: total revenue net of sales returns and allowances;

Operating income: revenue minus cost of revenues and total operating

expenses;

Net income: operating income net of interest expense, unusual items, tax

expense, and minority interest;

Cash from operations: total of net income, depreciation and amortization, and

certain “other” items;

Total debt: short-term borrowings, long-term debt, and long-term capital

leases;

Altman Z-Score: an index commonly used for predicting the probability that a

firm will go into bankruptcy within two years. The lower the score, the greater

the probability of insolvency; and

Number of employees.

Benefits Plan and looked for XYZ Corporation among Form 990 filings to determine

its for-profit status. To this end, we excluded Form 990 filings by Voluntary

Employees' Beneficiary Associations (VEBAs), Teachers Retirement Fund

Associations, Supplemental Unemployment Compensation Trusts or Plans, Employee-

Funded Pension Trusts, Multiemployer Pension Plans, and any filer with names that

include such labels as “health plan” or “welfare plan.” For-profit status thus refers to

the ultimate plan sponsor, not to the plan itself.

9

A Form 10-K is an annual financial report filed with the U.S. Securities and

Exchange Commission.

8

Matching Form 5500 Filings and Capital IQ Records

The only common field in Form 5500 health plan filings and the Capital IQ data

available to us is the company/sponsor name. In part because of spelling variations,

the match rate on name alone is low.

To obtain a better match rate, we used both EINs and company names. Form 5500

health plan data contain EINs, but the Capital IQ file available to us does not. Most

Capital IQ records, however, report the company’s Central Index Key (CIK), a

number used by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to identify

corporations and individuals who have filed a disclosure with the SEC. SEC filings,

electronically available from the SEC’s Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and

Retrieval (EDGAR) system, often include both a company’s CIK and its EIN. The CIK

can be used to link Capital IQ records to EINs from the SEC, and then the EIN can

link the Capital IQ-SEC record to Form 5500 filings.

10

Next, we defined clusters of EINs, CIKs, and company names that appeared to relate

to the same company. For example, a company may have used two EINs, or an EIN

may have been associated with multiple (similar) names. To improve the clustering,

we normalized the company names and removed plan labels (e.g., ABC Incorporated

Employee Benefit Trust is equivalent to ABC Inc.).

All related EINs, CIKs, and company names were mapped into a unique cluster ID.

Finally, we matched Capital IQ records and Form 5500 health plan filings by cluster

ID.

Corporate fiscal years need not correspond to health plan reporting periods. In an

effort to accurately match 2016 Form 5500 health plan filings with their sponsor’s

corresponding 2016 financial information, we required that the end date of the fiscal

year captured in Capital IQ and the end date of the Form 5500 plan year differed by

no more than 183 days. Only if the closest fiscal and plan years differed by no more

than 183 days did we consider this a match.

For example, a health plan sponsor could have a plan year from January 1 to

December 31, but a fiscal year that ran from April 1 to March 31 of the next year.

Under these circumstances, we would match the Form 5500 health plan filing ending

December 31, 2016 with the Capital IQ financial information for fiscal year ending

March 31, 2017.

Table 4 shows that we matched 3,918 plans, or about 7% of the plans in the 2016

Form 5500 health plan data.

11

This is the set of companies that appear in our

10

Some issues arose in the linking process. While about 15% of Capital IQ records

do not contain a CIK, 7% contain multiple CIKs. Also, some CIKs were found to be

linked to multiple EINs. These were incorporated in the analysis.

11

While this is a relatively small number, many companies that filed a Form 5500

are not represented in Capital IQ data because they may have no requirement to

issue publicly available financial statements. Sponsors may be privately held, based

overseas, or not-for-profit and without publicly issued bonds, or the plan may be a

multiemployer or multiple-employer plan.

9

matched analyses below. The 3,918 plans covered 27 million participants or

approximately 36% of all participants in the Form 5500 health plan data.

Table 4. Form 5500 Health Plan Filings Matched with Financial Information,

by Plan Size (2016)

Plans Participants

Num

ber of

Num

ber

par

ticipants

Num

ber

Per

cent

Mat

ch rate

(mi

llions)

Per

cent

Mat

ch rate

Zero 102 2.6% 5.5% 0.0 0.0%

1-9

9

124 3.2% 3.2% 0.0 0.0% 3.8%

100-199 410 10.5% 2.3% 0.1 0.2% 2.3%

200-499 678 17.3% 4.0% 0.2 0.8% 4.3%

500-999 533 13.6% 8.2% 0.4 1.4% 8.4%

1,000-1,999 564 14.4% 14.9% 0.8 3.0% 15.4%

2,000-4,999 640 16.3% 23.3% 2.1 7.7% 24.6%

5,000+ 867 22.1% 40.0% 23.4 86.8% 48.1%

Tot

al

3,918 100.0% 7.0% 27.0 100.0% 36.0%

Sou

rce: Form 5500 health plan filings and Capital IQ data.

Note: Numbers may not sum to totals due to rounding.

The match rate increases with plan size, presumably because large plans are

sponsored by large companies and larger companies are more likely to disclose

financial information than smaller companies. The match rate among plans with

5,000 or more participants is 40% (same as in 2015), i.e., more than one-half was

not matched. These include hospitals and universities without public financials, but

also plans sponsored by US operations of large international firms with public

financials. We restricted Capital IQ records to companies whose primary geographic

location is in the United States because the financial health of a foreign parent

company does not necessarily correspond to that of its US subsidiary. Mismatches

arose from differences between corporate names in Capital IQ (e.g., XYZ Holdings

Inc) and sponsor names on Form 5500 filings (e.g., XYZ Inc). A more inclusive name

matching algorithm could boost the matching rate, but it also increases the risk of

false matches which, in turn, could dilute any analysis results based on the matched

subset of plans. Instead, we opted for a more conservative approach with a smaller

subset of matched plans but more reliable matches.

12

12

The match rate for plans, 7.0%, is smaller than achieved using 2015 data (7.4%).

The reduction mirrors a decrease in the number of companies with public financials.

For example, the number of publicly listed companies dropped from 9,113 in 1997 to

5,734 in 2016 (“America’s Roster of Public Companies Is Shrinking Before Our Eyes,”

Wall Street Journal, January 6, 2017). Indeed, a manual review of large plan

sponsors that matched last year but not this year indicated that a substantial share

had merged with other companies, sometimes in conjunction with relocation

overseas.

10

3. THE DEFINITION OF SELF-INSURANCE

The Form 5500 does not require plan sponsors to specify the funding mechanism of

health benefits with sufficient specificity for us to determine whether plans that

report using both a trust and insurance should be classified for the purposes of this

report as self-insured, fully insured, or mixed funded. This section describes how we

determine funding mechanisms of individual plans for the purposes of this report.

The Definition of Funding Mechanism Is Driven by Available Data

As defined in this report, funding mechanism is based on information in Form 5500

health plan filings. Plans are categorized as self-insured, fully insured, or mixed-

funded. A mixed-funded plan contains both self-insured and fully insured

components. For example, an employer may offer its employees a choice between a

fully insured HMO option and a self-insured PPO option. If both plan components

were reported on a single Form 5500 filing, the plan would be mixed-funded. In

some cases, the data are incomplete or internally inconsistent. For example, while

Schedules A are intended to report on insurance contracts, some plans attached a

Schedule A for a contract that appears to be for administrative services only (ASO)

rather than for insurance. Given these limitations, the classification in this report

should not be interpreted as an official or legal definition. The definition of funding

mechanism is driven by available data. The data fields used by the algorithm are

provided in the Technical Appendix.

In 2016, 3,638 plans were identified as self-insured because they did not report any

health insurance contracts and the plan attached a Schedule H or I with evidence of

benefit payments; see Figure 2. Even though they did not attach a Schedule H or I,

another 20,066 plans were also identified as self-insured because they provided

other evidence of self-insurance: (1) the plan indicated that its funding or benefit

arrangement was, at least in part, through a trust or from general assets; (2) the

plan reported fewer than 100 participants and at least some financial information on

a Form 5500-SF;

13

(3) the plan reported 100 or more participants and non-zero

assets on a Form 5500-SF; or (4) the plan reported stop-loss coverage or payments

to a third-party administrator (TPA). In the absence of such evidence, 1,613 plans

were classified as fully insured. Some plans attached both a Schedule A with health

insurance payments, suggesting full insurance, and a Schedule H or I with trust

payments, suggesting self-insurance. For 318 of these plans, trust payments were

within 10% of payments for health or all insurance contracts, suggesting that they

used the trust to pass through insurance payments and that the plans were fully

insured; another 1,219 plans were classified as mixed-funded because their

insurance and trust payments were more than 10% apart.

13

Filers of a Form 5500-SF report financial information on the Form 5500-SF itself,

rather than on a Schedule H or I. We presume the following status for Form 5500-SF

filers:

Fewer than 100 participants, no financial information: voluntary filers,

excluded from the analysis;

Fewer than 100 participants, some financial information: self-insured;

100 or more participants, no assets: fully insured; and

100 or more participants, non-zero assets: self-insured.

11

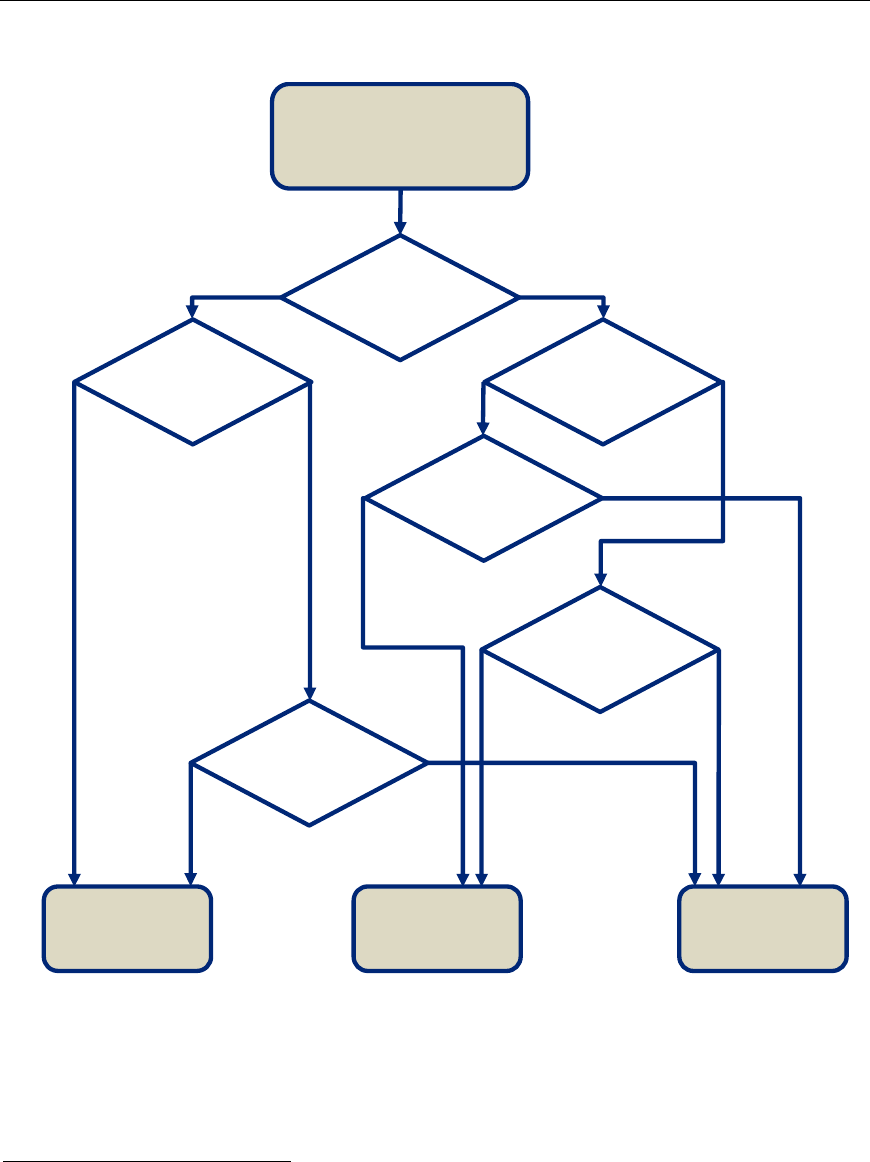

Figure 2. Funding Mechanism Derivation

Self-Insured

23,704 plans

(42%)

Mixed-Funded

4,098 plans

(7%)

Fully Insured

28,409 plans

(51%)

Attached

Schedule A

?

Attached

Schedule H/I

?

No

Evidence

of self-insurance

?

Yes

Trust and

insurance payments

within 10%

?

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

3,638

plans

20,066

plans

2,879

plans

1,219

plans

1,613

plans

318

plans

26,478

plans

Total 2016 plans

56,211 plans

Attached

Schedule H/I

?

Yes

No

No

Yes

No

Insurance

covered <50% of

participants

?

In a common scenario, plans reported health insurance payments on one or more

Schedules A and did not file a Schedule H or I. For these plans, we compared the

number of people covered through health insurance contracts to the number of plan

participants. If the number of people covered by a health insurance contract was less

than 50% of the number of plan participants, we classified the plan as mixed

funded.

14

This was the case for 2,879 plans. The remaining 26,478 plans whose

14

See our report, Strengths and Limitations of Form 5500 Filings for Determining the

Funding Mechanism of Employer-Provided Group Health Plans at

https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/ebsa/researchers/analysis/health-and-

welfare/strengths-and-limitations-of-form-5500-filings-for-determining-the-funding-

mechanism-of-employer-provided-group-health-plans.pdf for a discussion of the

sensitivity of plans’ funding categorizations to the 50% threshold.

12

health insurance covered at least one-half of plan participants were classified as fully

insured. In total, 23,704 plans (42%) were identified as self-insured, 4,098 plans

(7%) as mixed-funded, and 28,409 plans (51%) as fully insured.

While this approach is subject to some data quality issues (further discussed below),

we believe it results in a meaningful characterization of health plans’ funding

mechanism.

Issues in Defining Funding Mechanism

The information on Form 5500 may be incomplete or inconsistent. Some of the

issues affecting the funding mechanism definition are as follows:

According to subject matter specialists, an employer may set up a subsidiary

that acts as an in-house insurance company and sells health insurance to

employees. These “captive” insurance companies are subject to state

regulations regarding insurance companies. Plan sponsors purchasing

insurance from a captive insurance company would file a Schedule A, which

does not require disclosing that the insurance company is captive. In the

classification, such plans would thus be considered fully insured, even though

the employer group to which they belong is incurring a risk substantially

similar to that of a self-insured plan. Since nothing on the Form 5500 permits

the identification of captive insurance companies, we were not able to

quantify how frequently this issue arises.

As explained above, 7% of Form 5500 filing health plans contained both

externally insured and self-insured health components in 2016. While the

distinction may be clear conceptually, Form 5500 data limitations imply that

the health plan as a whole must be categorized as mixed-funded (partially

self-insured and partially insured). The issue arises in part because Form

5500s are required for each plan, not for each type of benefit offered under a

plan. Where a plan provides multiple types of welfare benefits or multiple

types of health benefit options, it is not always possible to attribute responses

to the health benefit component(s) of the filer’s welfare plan. Also, a plan

may indicate funding benefits through insurance contracts and from general

assets without specifying which plan components are funded in either way.

Separately, Form 5500 data limitations arise from the fact that the Form 5500

does not ask details about self-insured plan components. At the

participant/policy level, however, a benefit is either self-insured or fully

insured.

As noted, plans may attach both one or more Schedules A (evidence of

insurance) and a Schedule H or I (evidence of a trust suggesting self-

insurance). If trust payments were within 10% of insurance payments, we

conclude that the trust passes through insurance payments and classify the

plan as fully insured. However, if the trust and insurance payments differ by

more than 10%, the plan is classified as mixed-funded. The 10% criterion

may not always accurately distinguish funding types, especially if insurance

contracts and trusts have different fiscal years.

Also, as noted above, plans may offer self-insured health benefits to some

participants and fully insured benefits to others, but the Form 5500 provides

little insight about the number of participants in the self-insured component.

Reflecting such scenarios, plans may also be classified as mixed-funded if

fewer than 50% of plan participants are covered by health insurance

13

contracts. The comparison is less than perfect. First, the number of “persons

covered” by insurance contracts, as reported on Schedule A, may be

interpreted as inclusive of dependents, whereas the definition of “participant”

for Form 5500 explicitly excludes dependents (see 2016 Instructions for Form

5500). Second, on plans that provide multiple types of benefits, not all

reported participants may in fact be participants in the health benefits

component of the plan.

The classification may not recognize mixed funding due to carve-out services.

For example, a plan may purchase insurance coverage for mental health

benefits and self-insure other health benefits. Its Form 5500 filing would

include a Schedule A with details of the mental health carve-out but might list

the benefits provided under the contract as “group health” because there isn’t

a separate category for “mental health” benefits on Schedule A, as there is for

“dental,” “vision,” and “prescription drugs.”

Some plans may have filed a Schedule A for an ASO contract even though

such a contract is not an insurance contract and the instructions advise filers

not to file a Schedule A for an ASO contract. We attempted to identify such

Schedules A through potentially reported TPA payments, stop-loss coverage,

or implausibly low per-person premium amounts, but the process may not be

perfect.

Among plans that reported a funding or benefit arrangement through

insurance, approximately 0.7% did not file a Schedule A with insurance

contract details. In such cases, it was assumed that the plan was fully

insured.

Among plans that reported a funding or benefit arrangement through

insurance, approximately 1.6% filed one or more Schedules A without the

type of benefit that the insurance contract covered. In such cases, unless

they had also filed another Schedule A for health insurance, it was assumed

that the insurance contract provided health benefits.

For more details on data anomalies that stood in the way of unambiguous funding

mechanism classifications, see our report on Strengths and Limitations of Form 5500

Filings for Determining the Funding Mechanism of Employer-Provided Group Health

Plans.

15

Stop-Loss Insurance

While self-insured plans bear the financial risks of health benefits and claims, some

self-insured plans purchase insurance against particularly large losses. As discussed

in the Analysis section below, roughly one in four self-insured plans report such

catastrophic or stop-loss insurance on their Form 5500 health plan filings.

16

While

stop-loss coverage mitigates financial risks, the plan is still considered self-insured or

mixed-funded.

15

Available at https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/ebsa/researchers/analysis/

health-and-welfare/strengths-and-limitations-of-form-5500-filings-for-determining-

the-funding-mechanism-of-employer-provided-group-health-plans.pdf.

16

As also explained in the Analysis section, if the beneficiary of stop-loss insurance is

the employer/sponsor rather than the plan and it was not purchased with plan

assets, it need not be reported on Form 5500. The true prevalence of stop-loss

insurance, therefore, cannot be gleaned from Form 5500 health plan filings alone.

14

4. ANALYSIS

This section documents the findings of our analyses. We first present the Form 5500

distribution of funding mechanism by plan and plan sponsor characteristics. We then

turn to health plan sponsors for which external financial information was available

and present summary statistics for these sponsors by plan funding mechanism. Next,

we follow plan filings over time and document the rate at which plans have switched

funding mechanisms.

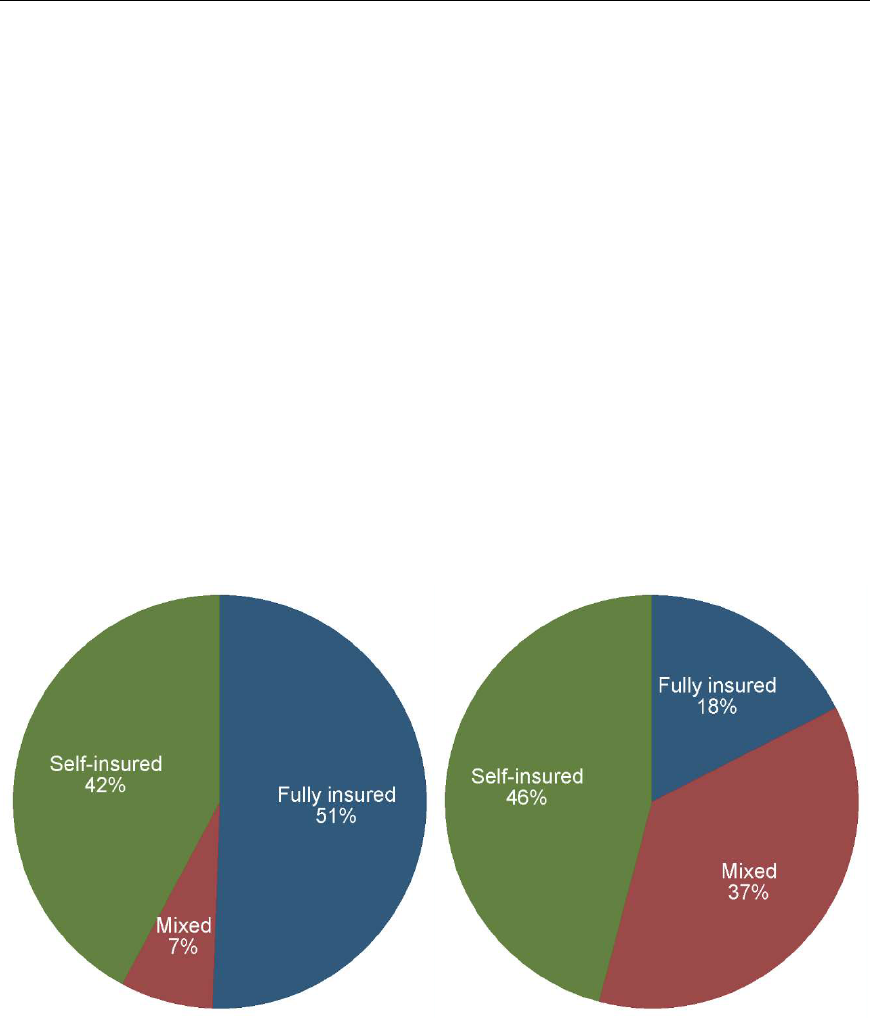

Funding Mechanisms for Plans and Participants

For statistical year 2016, Figure 3 shows the overall distribution of funding

mechanism among the 56,211 health plans that filed a Form 5500. About 51% of

plans were fully insured, 42% were self-insured, and 7% were mixed-funded. As

shown further below, smaller plans tend to be fully insured and many very large

plans are mixed-funded, so the funding distribution across participants is quite

different than it is across plans. About 18% of the 75 million participants were in

fully insured plans, 46% were in self-insured plans, and 37% were in mixed-funded

plans. (Percentages do not sum to 100% due to rounding.)

Figure 3. Distribution of Funding Mechanism (2016)

Plans Participants

*

*

Percentages do not sum to 100% due to rounding.

To put our analysis in context, consider recent trends in self-insurance according to

two external sources. First, the Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research &

Educational Trust annually gather detailed information on employer-provided health

benefits, including their funding status, in Employer Health Benefits 2017 Annual

15

Survey (“KFF/HRET Survey”).

17

It found that 61% of covered workers in firms with

three or more employees were in partially or completely self-funded plans in 2016.

18

Our findings are not directly comparable, because our analysis covers only a small

subset of plans with fewer than 100 participants and because as many as 37% of

plan participants are in mixed-funded plans. Given the limitations of Form 5500

health plan filings, our results are broadly consistent with those found in the

KFF/HRET Survey.

Second, similar to the KFF/HRET Survey, the Insurance Component of the Medical

Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS-IC) annually surveys employers about the health

benefit plans they offer.

19

Again, the findings are not strictly comparable, in part

because the unit of observation is an establishment in the MEPS-IC and a plan in the

Form 5500 data, and because size is measured in covered employees in the MEPS-IC

and plan participants in the Form 5500. That said, the results are similar. According

to the MEPS-IC, 34% of establishments with 100-999 employees self-insured at least

one plan in 2016, whereas we found that 40% of plans with 100-999 participants

were self-insured or mixed-funded (calculated from the numbers underlying Table 5

below). Weighted by employees (MEPS-IC) or participants (Form 5500), the fractions

are 37% and 48%, respectively. For larger establishments (or plans) with 1,000 or

more employees (or participants), 82% self-insured at least one plan according to

the MEPS-IC and 83% were self-insured or mixed-funded according to Form 5500

filings. Weighted by employees (MEPS-IC) or participants (Form 5500), the fractions

are 83% and 90%, respectively.

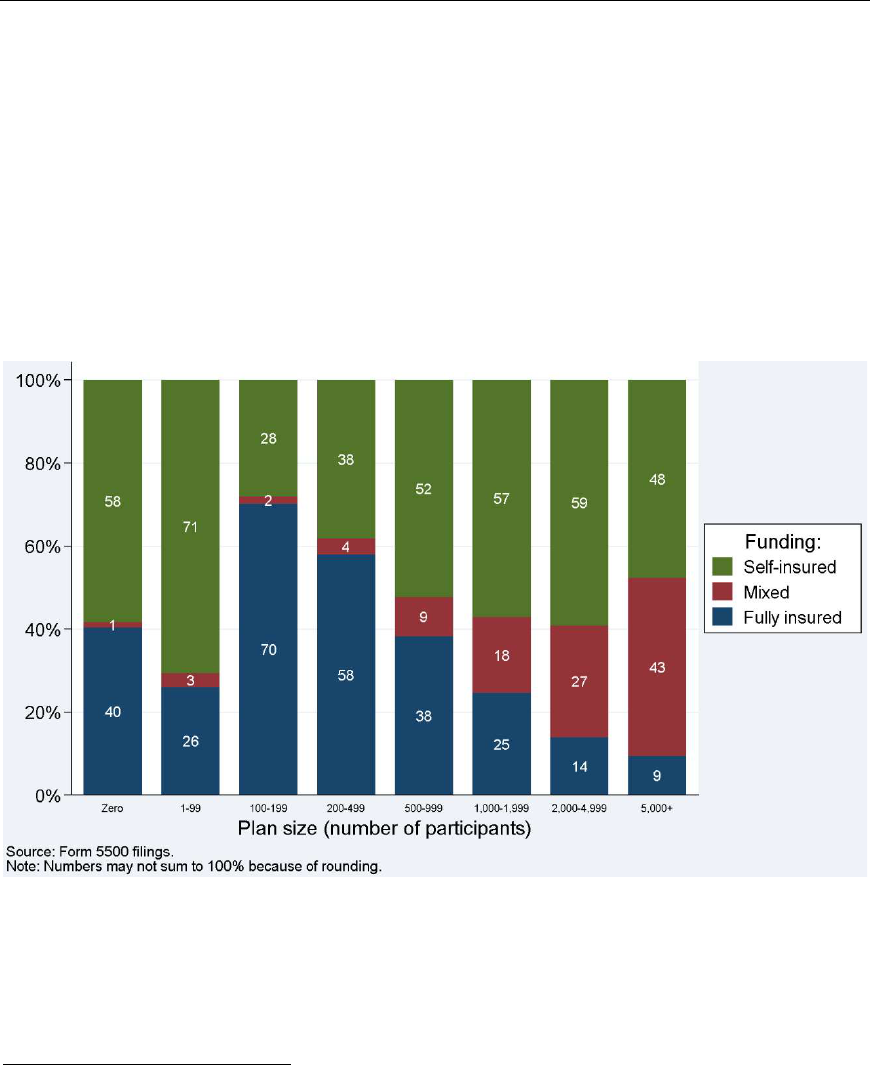

Funding Mechanisms by Plan Size

Figure 4 shows the distribution of funding mechanism by plan size for health plans in

2016. Most small plans are identified as self-insured in our study, but this is

presumably due to the select nature of small plans in our analysis. Plans with fewer

than 100 participants generally are required to file a Form 5500 only if they use a

trust or separately maintained fund to hold plan assets or act as a conduit for the

17

Employer Health Benefits, 2017 Annual Survey. Kaiser Family Foundation and

Health Research & Educational Trust. Available at

http://kff.org/health-costs/report/2017-employer-health-benefits-survey.

18

The KFF/HRET survey defines covered workers as “employees receiving coverage

from their employer.”

19

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Insurance Component Chartbook 2016.

Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, September 2017. AHRQ

Publication No. 17-0034-EF. Available at

https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/cb21/cb21.pdf.

16

transfer of plan assets, which is often associated with self-insurance.

20,21

Plans with

fewer than 100 participants that are fully insured or pay benefits from the general

assets of the employer and that are not MEWAs required to file the Form M-1 are not

required to file a Form 5500 and, therefore, are not included in this analysis.

22

Apart

from plans with fewer than 100 participants, the likelihood that a plan is self-insured

generally increases with plan size. The pattern is particularly pronounced for mixed-

funded plans, presumably because larger plans may offer multiple plan options,

some of which are fully insured and some of which are self-insured. The share of

plans with 5,000 or more participants that are self-insured or mixed-funded is 91%,

compared with 30% among plans with 100-199 participants.

Figure 4. Distribution of Funding Mechanism, by Plan Size (2016)

20

Self-insured plans with fewer than 100 participants, without trust assets, and that

are not MEWAs required to file the Form M-1 are generally not required to file a Form

5500 and are therefore not in the analysis. These may include so-called level-funded

plans.

21

The analysis inclusion is based on participants at the beginning of the plan year,

whereas Figure 4 distinguishes plans based on their number of participants at the

end of the year. Some plans with fewer than 100 participants at the beginning of the

year may therefore be included in categories with 100 or more participants at the

end of the year, and vice versa.

22

This applies to the vast majority of small health plans; see footnote 2 on page 2.

17

Table 5 shows the numbers underlying Figure 4. It also shows the participant-

weighted distribution of funding mechanism by plan size, which is similar to the plan-

weighted distribution.

Table 5. Distribution of Funding Mechanism, by Plan Size (2015)

Participants Plans Participants

in plan Fully insured Mixed Self-insured Fully insured Mixed Self-insured

Zero 40.3% 1.3% 58.4%

1-99 26.0% 3.3% 70.7% 42.4% 3.5% 54.1%

100-199 70.1% 1.7% 28.1% 69.8% 1.8% 28.4%

200-499 58.0% 3.8% 38.2% 56.5% 4.1% 39.4%

500-999 38.3% 9.5% 52.3% 37.4% 9.9% 52.7%

1,000-1,999 24.6% 18.3% 57.1% 24.2% 19.0% 56.8%

2,000-4,999 13.9% 26.9% 59.1% 13.4% 27.8% 58.8%

5,000+ 9.4% 42.9% 47.7% 8.5% 48.1% 43.4%

All 50.5% 7.3% 42.2% 17.5% 36.6% 45.9%

Sourc e: Form 5500 health plan filings.

The finding that larger plans are more likely to adopt mixed-funding or self-insurance

is consistent with the 2016 KFF/HRET Survey. That study found that 13% of covered

workers at firms with 3-199 employees were covered by self-insured plans in 2016,

compared with 94% of covered workers at firms with 5,000 or more employees.

Funding Mechanisms by Year

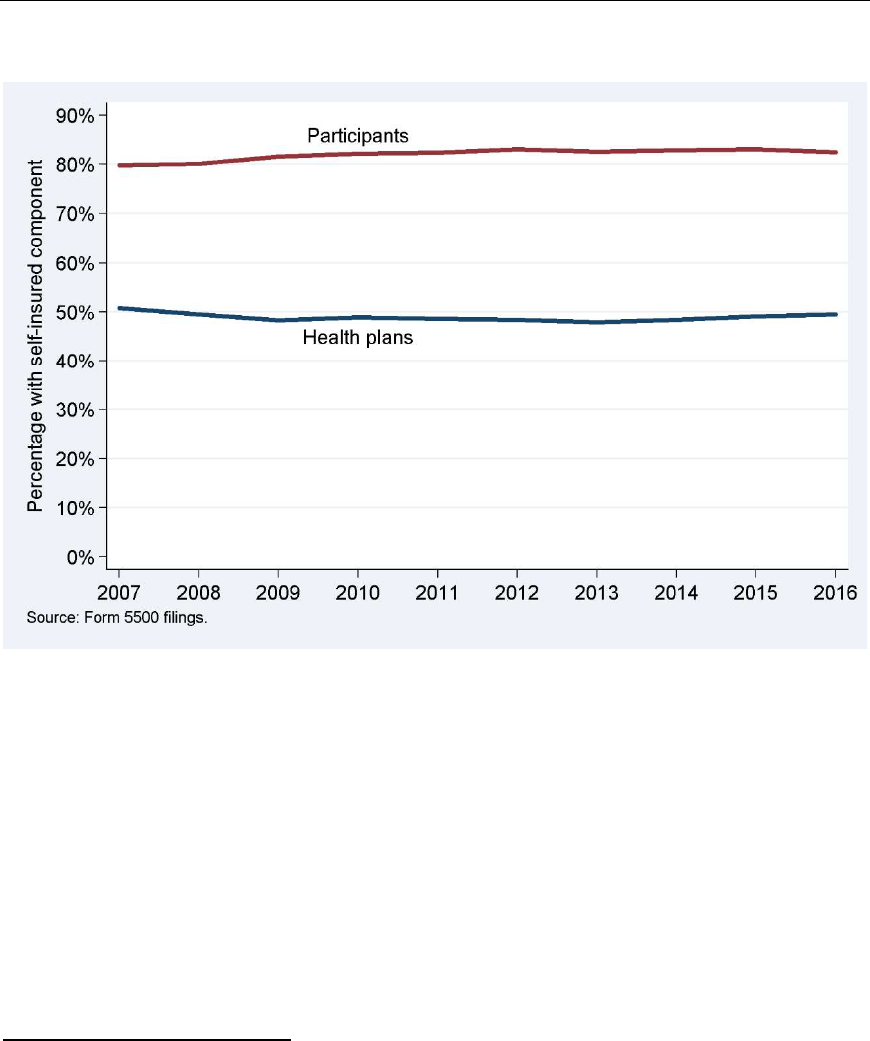

Figure 5 shows the funding mechanism distribution for health plans by statistical

year for 2007-2016. The percentage of plans that were self-insured or mixed-funded

generally declined from 51% in 2007 to 48% in 2009, was approximately flat

through 2013, and then slightly increased to 49% in 2016. While the general trend

among plans over the first few years of the past decade was away from self-

insurance, the share of participants in health plans that self-insured or were mixed-

funded increased by about 3 percentage points from 80% in 2007 to 83% in 2012

and remained approximately flat thereafter. In comparison, the KFF/HRET Survey

documented a continuing increase toward self-insurance, up 5 percentage points

between 2007 and 2012, and another 3 percentage points by 2015. However,

KFF/HRET reported that the self-insured or mixed-funded rate subsequently dropped

by 3 percentage points between 2015 and 2017. Thus, the overall trend toward self-

insurance among participants appears to have flattened out based on findings from

both this study and the KFF/HRET study.

23

23

The participant-weighted share of plans with a self-insured component slightly

decreased from 83.1% in 2015 to 82.5% in 2016 (see Figure 5 and Table 6). This

decrease appears to be related to three large plans that were new to the analysis in

2016 and were fully insured. While they indicated providing health benefits, their

primary purpose appears to be travel insurance benefits. The number of participants

in these three plans was approximately 734,000 (1.0% of participants in all plans

combined).

18

Figure 5. Distribution of Funding Mechanism, by Statistical Year

Table 6 provides additional details on the percentages underlying Figure 5, with

separate series for the mixed-funded and self-insured categories.

24

Table 7 further

shows the corresponding plan and participant counts. The total number of health

plans in each year was between approximately 45,000 and 56,000 and the number

of participants was between approximately 67 million and 75 million.

24

As also noted in past reports, Figure 5 and Table 6 pose a paradox: the share of

plans that were mixed-funded or self-insured generally decreased in the early part of

the past decade, but the share of participants in such plans generally increased. The

paradox may be explained as follows. First, self-insurance has become less prevalent

among relatively small plans (100-499 participants) and more prevalent among

relatively large plans (500 or more participants). Second, the fraction of plans with

fewer than 100 participants in the data decreased. The analysis includes such plans

only if they operated a trust, which tends to be associated with self-insurance. The

combined result is that fewer plans are mixed-funded or self-insured, but those plans

cover increasingly more participants. For further discussion see the 2018 version of

this report.

19

Table 6. Distribution of Funding Mechanism, by Statistical Year

Statistical Plans Participants

year Fully insured Mixed Self-insured Fully insured Mixed Self-insured

2007 49.3% 7.5% 43.3% 20.2% 34.9% 44.9%

2008 50.5% 7.6% 41.9% 19.9% 35.5% 44.6%

2009 51.7% 7.6% 40.7% 18.4% 37.7% 43.9%

2010 51.1% 7.4% 41.6% 17.9% 37.5% 44.6%

2011 51.4% 7.5% 41.1% 17.6% 37.1% 45.3%

2012 51.6% 7.3% 41.0% 17.0% 36.8% 46.2%

2013 52.1% 7.5% 40.4% 17.4% 37.3% 45.2%

2014 51.6% 7.3% 41.0% 17.1% 36.5% 46.4%

2015 50.9% 7.2% 42.0% 16.9% 36.2% 46.8%

2016 50.5% 7.3% 42.2% 17.5% 36.6% 45.9%

Source: Form 5

500 health plan filings.

Note: Participant percentages may not be consistent with participant numbers in

Table 7 because they are calculated based on non-rounded numbers.

Table 7. Plans and Participants by Funding Mechanism, by Statistical Year

Statistical

Plans Participants (millions)

year Fully insured Mixed Self-insured Fully insured Mixed Self-insured

2007

23,124

3,509

20,303

13.8

23.7

30.6

2008 22,815 3,448 18,921 13.5 24.1 30.3

2009 24,333 3,602 19,169 12.3 25.1 29.2

2010 25,210 3,628 20,503 12.2 25.5 30.4

2011 25,098 3,669 20,088 12.0 25.4 31.0

2012 25,510 3,614 20,275 11.7 25.4 32.0

2013 26,183 3,774 20,270 12.1 26.0 31.5

2014 26,657 3,795 21,191 12.1 25.8 32.8

2015 27,723 3,905 22,860 12.3 26.3 34.0

2016 28,409 4,098 23,704 13.2 27.5 34.5

Source: Form 5500 health plan filings.

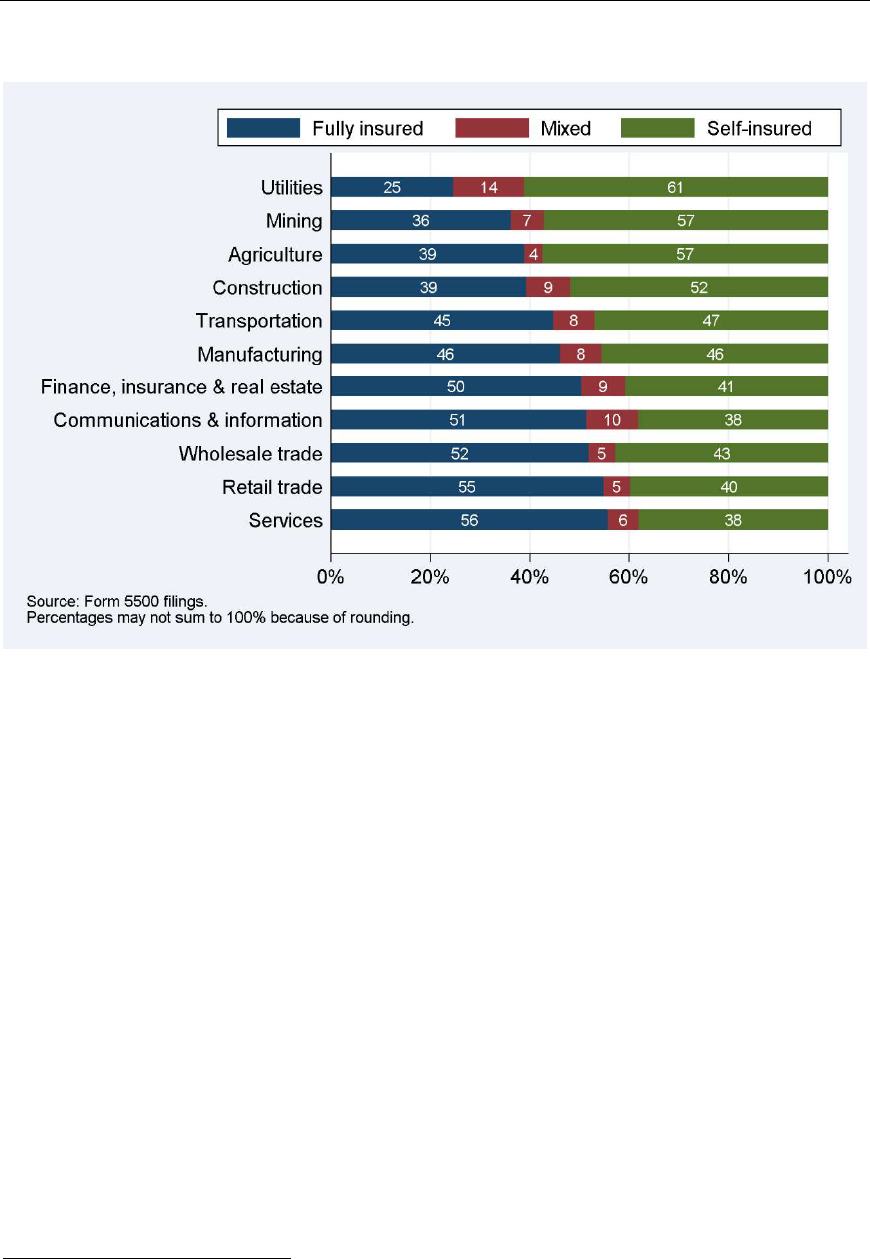

Funding Mechanisms by Industry

Figure 6 shows the funding mechanism distribution by industry, as identified by the

business code provided on Form 5500 filings. We present the percentage breakdown

of plans by the funding mechanism for a classification of major industry groups.

Plans in the utilities, mining, agriculture, and construction industries are the most

likely to be mixed-funded or self-insured, whereas the services and retail trade

industries are the most likely to be fully insured. Some of the relationship between

funding mechanism and industry may be due to variation across industries in health

plan sizes.

20

Figure 6. Distribution of Funding Mechanism, by Industry (2016)

Some industry patterns do not appear consistent with those documented by the

2016 KFF/HRET Survey. That study found that the agriculture/mining/construction

industry had below-average and retail above-average self-funding rates. Part of the

difference may be due to small plans, which were included in the KFF/HRET Survey

but mostly excluded from our analysis. Part may also be due to the fact that

KFF/HRET figures are for participants, whereas Figure 6 relates to plans. Weighted

by participants, we also find an above-average self-funding rate for plans in the retail

sector.

Funding Mechanisms over the Life Cycle of Plans

We noted earlier that plans tended to move toward full insurance over the first few

years of the past decade, whereas the fraction of participants in fully insured plans

was generally declining (Figure 5). Underlying this paradox is a divergence of smaller

and larger plans: smaller plans have tended to move toward full insurance whereas

larger plans have tended to move toward self-insurance (Footnote 24). In an attempt

to gain a fuller understanding of these trends, we now turn to funding mechanisms

over the life cycle of plans.

25

We distinguish among plans at the beginning of their life, at the end of their life, and

during the years in between. For example, it is unclear whether the observed shifts

were due to the funding mix of new plans, the funding mix of terminating plans, net

switches among established plans, or a combination of factors. The analysis is

25

For the lifecycle perspective in this section, we follow filings of individual plans

over time. In order to minimize gaps, the analysis includes voluntary filings.

21

somewhat hampered by the fact that Form 5500 filings contain incomplete

information about the beginning and end of plans’ lives:

New: We identify the beginning of a plan’s life cycle based on the Form

5500’s “first return/report” check box.

26

Cease filing: We attempt to capture the end of a plan’s life cycle in two ways.

First, a plan may have indicated on its Form 5500 that it is terminating,

namely by checking the “final return/report” box, by reporting a resolution to

terminate the plan, or by documenting that all assets were transferred out of

the plan.

27

Second, a plan may stop filing a Form 5500 without prior

indication. Doing so does not necessarily imply that the plan terminated; it

may be non-compliant or it may have shrunk and become exempt (and

neglected to note this by writing “4R” on Line 8b of the Form 5500). To

mitigate this issue, we ignore gaps in filings. Recognizing that some plans in

this category have in fact not reached the end of their life cycle, we label

them as plans that “ceased filing.”

28

Established: This category captures the middle of a plan’s life cycle. Plans that

were neither “new” nor “ceased filing” are labeled “established” plans.

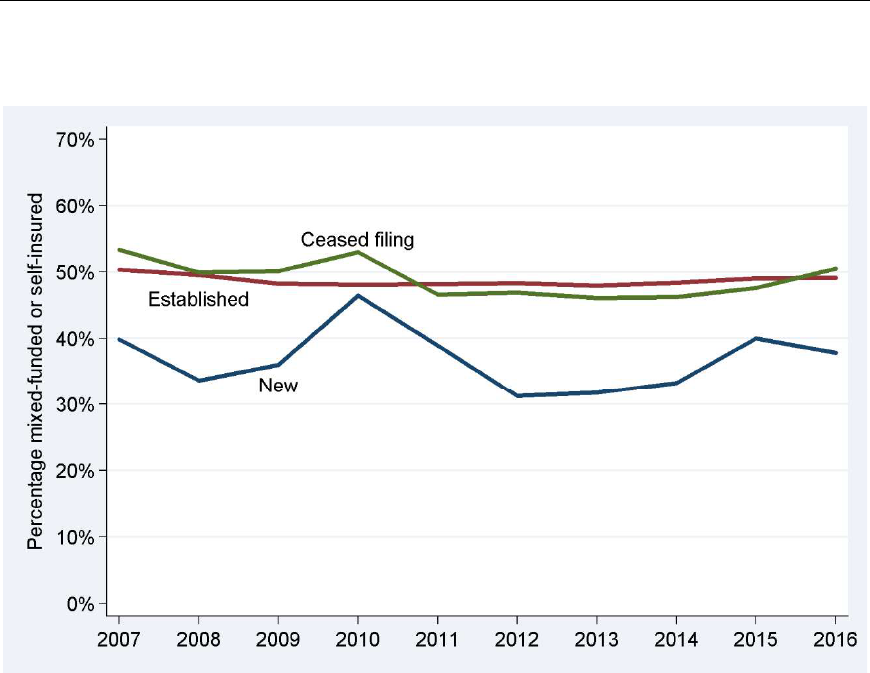

We will discuss plan-level and participant-level trends separately. Starting with plan-

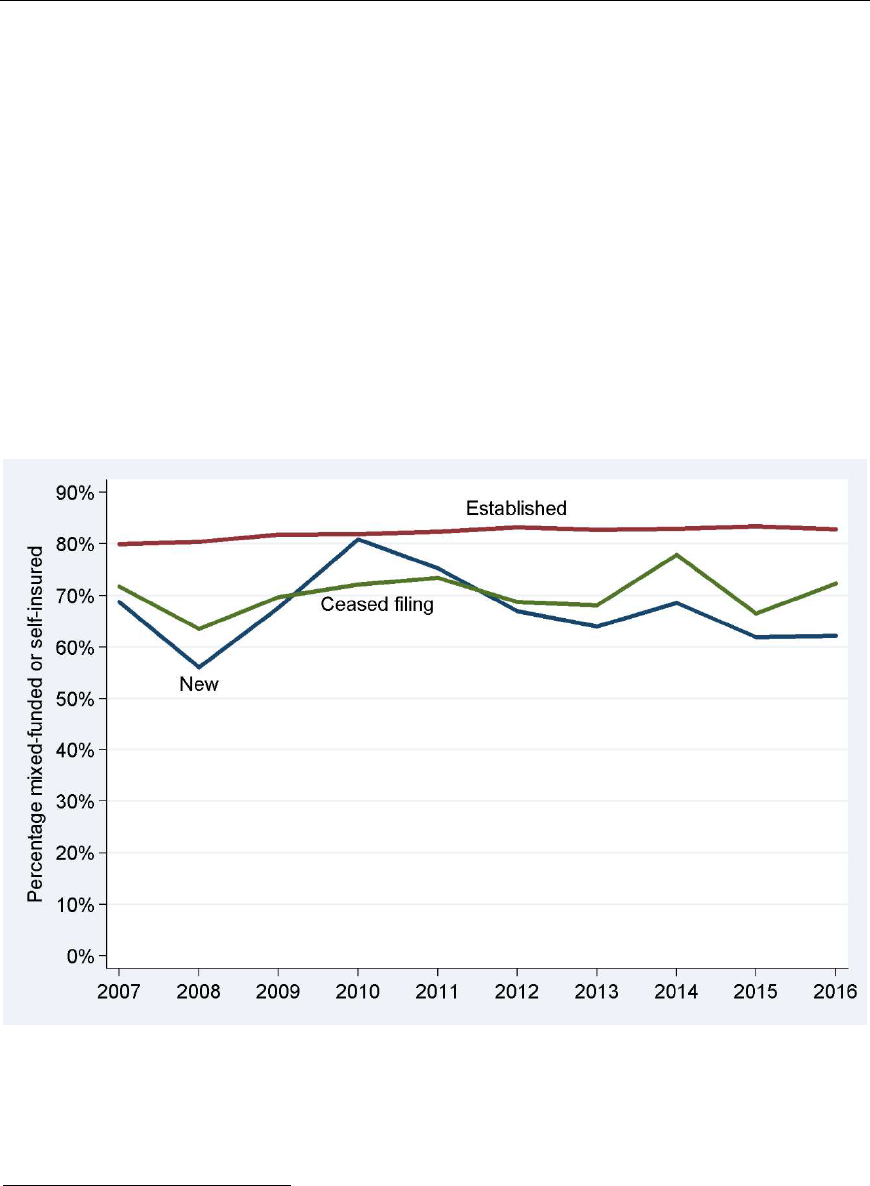

level developments, Figure 7 shows the mixed-funded or self-insured share of new

plans, established plans, and plans that ceased filing. (Since most plans are

established, the overall share is very close to the share among established plans.)

New plans were more often fully insured than other plans, but the self-insurance gap

between new plans and other plans was narrower in 2015 and 2016 than in most

previous years, which helps explain the slight reduction in full insurance in recent

years (Table 6).

29

26

Some plans never checked that box, or not until later in their life cycle. If the box

was not checked until the, say, fourth filing, we exclude the earlier filings from the

analysis. If the box was checked multiple times, we identify the plan as “new” only

the first time.

27

Some plans repeatedly indicated terminating but continued submitting filings. We

ignore indications of terminating if the plan continued filing in subsequent years.

Separately, plans that reported termination on their initial filing were included in

both the “new” and “ceased filing” categories. Also see Figure 10 below.

28

In terms of timing, if a plan indicated on its 2013 filing that it was terminating, we

consider it as having ceased filing in 2013. If a plan submitted filings through 2013

but not in any later year, we consider it as having ceased filing in 2014.

29

The number of new plans in 2016 was 4,573: 2,844 fully insured plans (62%), 138

mixed-funded plans (3%), and 1,591 self-insured plans (35%). New plans covered

approximately 2,127,000 participants: approximately 803,000 in fully insured plans

(38%), 561,000 in mixed-funded plans (26%), and 763,000 in self-insured plans

(36%).

22

Figure 7. Percentage Mixed-Funded or Self-Insured among New Plans,

Established Plans, and Plans That Ceased Filing, by Statistical Year

Changes in Mixed/Self-Insurance Due to Plans Switching Funding Mechanism

This section discusses funding mechanism switch rates among new and established

plans and the resulting flows of plans toward or away from self-insurance.

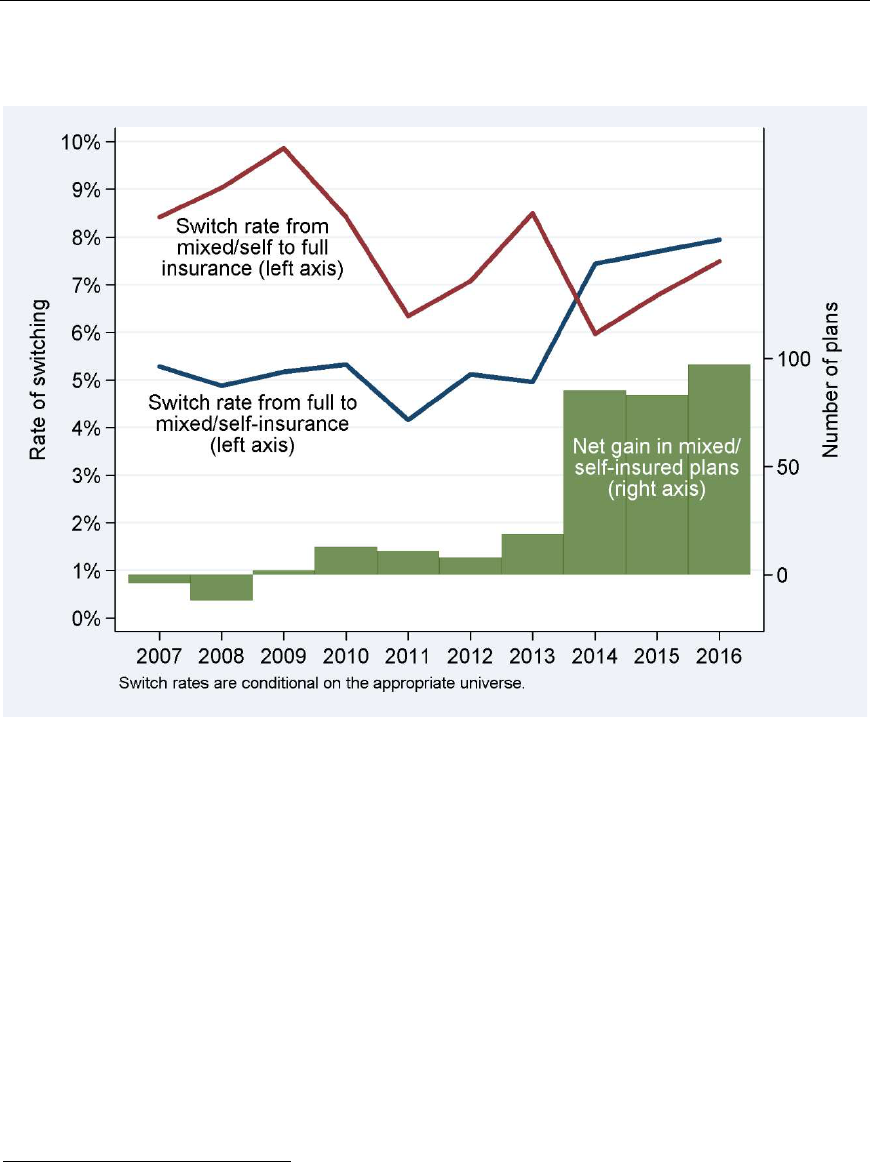

Figure 8 shows the switch rate for new plans over time, i.e., funding mechanism

changes between plans’ first and second filings. Through 2013, mixed-funded or self-

insured plans were more likely to switch to full insurance (red line) than fully insured

plans were to switch to a form of self-insurance (blue line). For example, 8.5% of

plans that started in 2012 as mixed-funded or self-insured had switched to full

insurance by 2013, compared with 5.0% of fully insured plans that had switched to

mixed funding or self-insurance. This does not mean that the net flow of plans was

toward full insurance: Figure 7 above showed that about 31% of new plans in 2012

were self-insured or mixed-funded, so the number of plans switching toward self-

insurance (5.0% of 69%) is slightly higher than plans moving toward full insurance

(8.5% of 31%). Indeed, the net flows were very small from 2005 through 2013, with

fewer than 10 plans annually, on net, moving in one direction or the other (green

bars).

23

Figure 8. Rates of Funding Switching among New Plans and the Resulting

Net Gain in Plans with a Self-Insured Component, by Statistical Year

Switch rates reversed in recent years. In 2014-2016, new plans were more likely to

switch toward self-insurance than away from it. On net, 85-97 new plans annually

switched toward self-insurance in 2014-2016 (green bars). Both recently increasing

self-insurance rates among new plans (Figure 7) and recently increasing switch rates

to self-insurance in plans’ second year of life (Figure 8) help explain the recent uptick

in overall self-insurance rates.

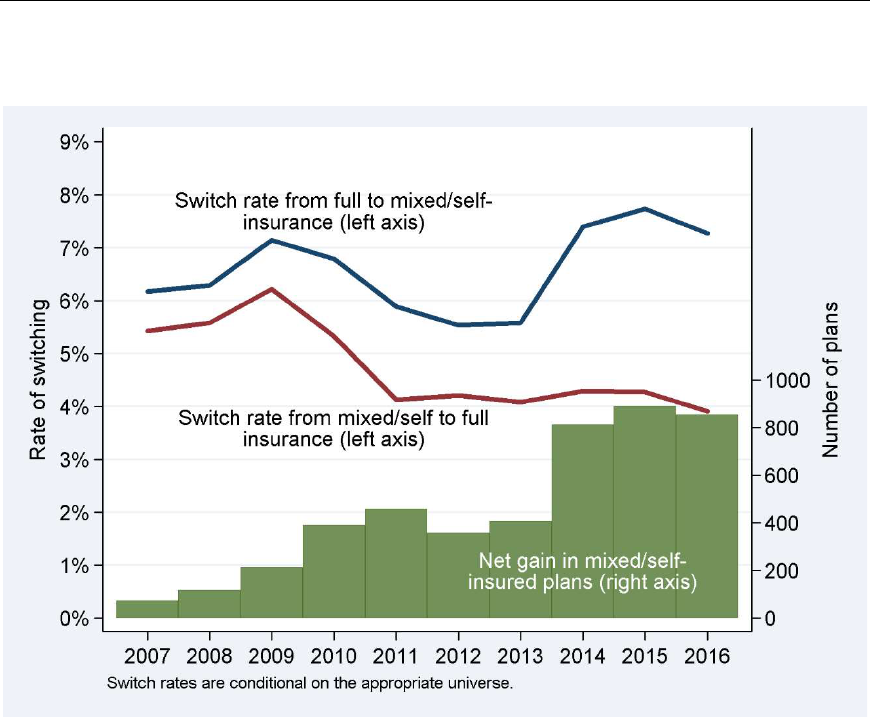

Similarly, Figure 9 shows the switch rate for established plans over time and the

resulting net flow of plans toward self-insurance. Switch rates are higher toward self-

insurance (blue line) than away from it (red line), especially since 2014. For

example, 3.9% of established plans that in 2015 were mixed-funded or self-insured

had switched to full insurance by 2016, compared with 7.3% of fully insured plans

that had switched to mixed funding or self-insurance.

30

30

Some plans appear to switch funding mechanisms more often than is plausible. In

some cases, the issue is that two plans—one insured, one self-insured—are reported

with the same EIN and PN. In other cases, incomplete or ambiguous information on

Form 5500 filings may result in conflicting categorizations from one year to the next.

The switching rates in Figure 9 may thus overstate true switching rates, but the net

effect on plan flows should be approximately zero.

24

Figure 9. Rates of Funding Switching among Established Plans and the

Resulting Net Gain in Plans with a Self-Insured Component, by Statistical Year

Again, the switch rate patterns in Figure 9 do not necessarily reflect flows of plans

because of (small) differences in the numbers of established plans that were fully

insured or mixed-funded/self-insured. The green bars indicate the net gains in plans

with a self-insured component as a result of switching by established plans. On net,

switching by established plans added to the number of plans with a self-insured

component, especially starting in 2014. The flows were larger among established

plans than among new plans, with approximately 800 plans annually moving toward

self-insurance in 2014-2016.

Figure 5 showed that until about 2010, an increasing share of health plans were fully

insured; switch patterns among new plans contributed very little to that trend, and

the green bars in Figure 9 demonstrate that switch patterns among established plans

went counter to the overall trend. In 2014-2016, consistent with switch patterns

among new and established plans, the prevalence of mixed-funding or self-insurance

increased slightly.

Changes in Mixed/Self-Insurance Due to Plans Ceasing Filing

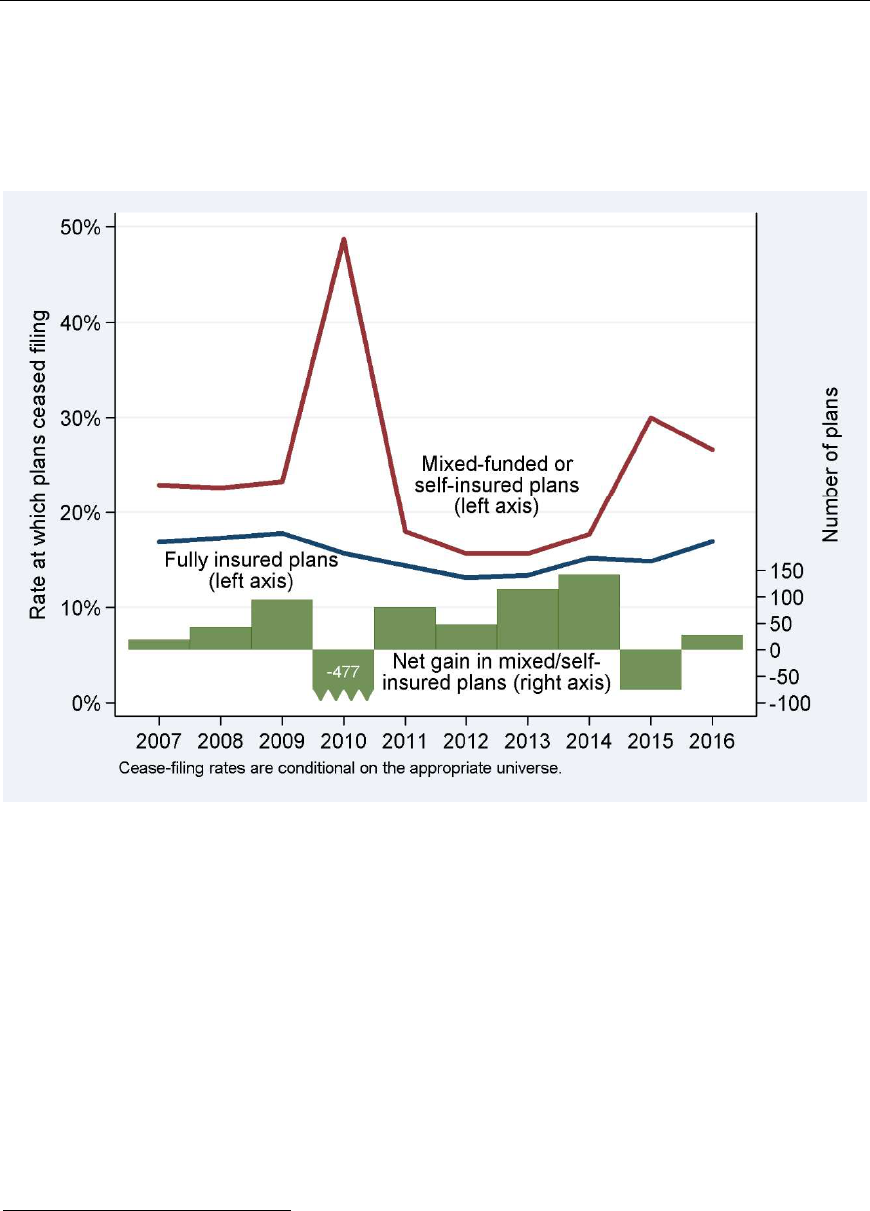

Figure 10 shows the rates at which new plans ceased filing; they could have checked

both the first and final return/report checkboxes, or they could have filed just a

single Form 5500. In all years from 2007 to 2016, mixed-funded or self-insured new

plans were more likely to cease filing (red line) than their fully insured counterparts

25

(blue line).

31

In terms of absolute numbers, more fully insured plans terminated,

resulting in relatively more remaining plans with a self-insured component (green

bars), except in 2010 and 2015.

Figure 10. Rates at Which New Plans Ceased Filing, by Statistical Year

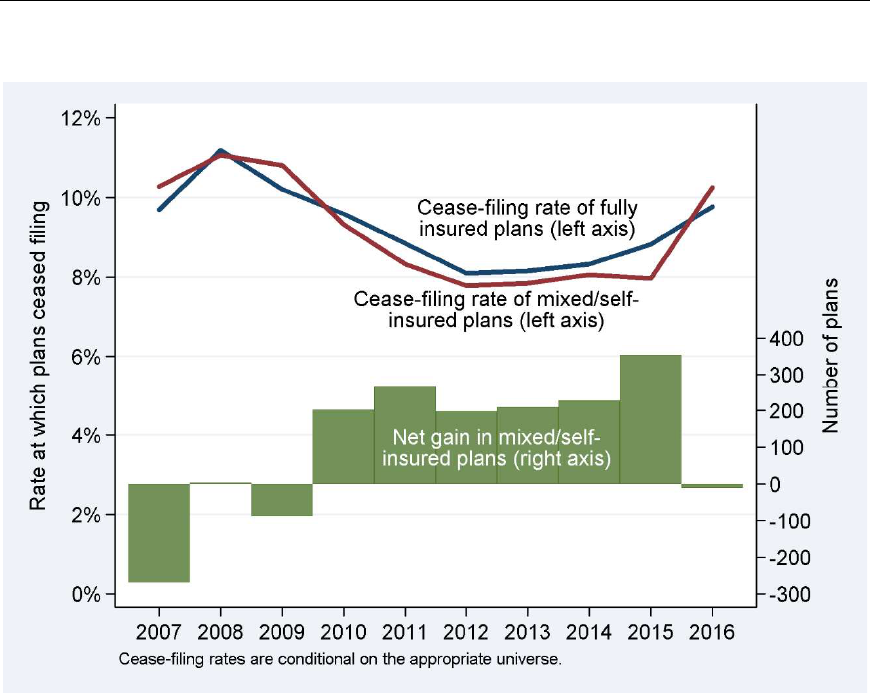

Similarly, Figure 11 shows that rates at which established fully insured plans ceased

filing (blue line) were generally close to those of mixed-funded or self-insured plans

(red line). Until 2009, the net effect was a decrease in the prevalence of mixed/self-

insured plans (green bars). In 2010-2015, fully insured plans ceased filing in larger

numbers than mixed-funded or self-insured plans, while in 2016 the flows were

approximately equal.

31

The spike in 2010 appears to be an anomaly due to a single administrator who

submitted more than 800 Form 5500 filings for small, self-insured plans in 2010 and

checked both the first and final return/report boxes. No such explanation is evident

for the increase in 2015-2016.

26

Figure 11. Rates at Which Established Plans Ceased Filing

In conclusion, the share of plans that were fully insured was increasing until 2013.

This was mostly caused by new plans and, up to 2009, was amplified by patterns in

the number of plans that ceased filing. The majority of new plans were fully insured.

The net effect of changes in funding mechanism over the life cycle went in the

opposite direction, with more plans switching toward mixed/self-insurance than

toward full insurance. Up to 2009, more mixed-funded or self-insured plans ceased

filing than fully insured plans did, but that pattern reversed starting in 2010. Indeed,

the overall trend among plans toward full insurance leveled out starting around 2010

(see Figure 5 and Table 6). Starting in 2014, the trend toward full insurance

reversed because of increased self-insurance among new plans (Figure 7), and more

net switching to self-insurance by new plans (Figure 8) and established plans (Figure

9).

The ACA was enacted in 2010 and many of its provisions became effective in 2014,

which coincides with increased self-insurance among new plans and increased net

switching toward self-insurance among all plans. While our analysis of the trends

documented above is agnostic with respect to causality, it is possible that the ACA

prompted elevated interest in self-insurance. We emphasize that the changes were

moderate; the share of plans with a self-insured component rose from 47.9% in

2013 to 49.5% in 2016 (see Figure 5 and Table 6).

Small and Large Plans Behaved Differently

The discussion above generally ignored plan size. However, while the overall fraction

of plans that are fully insured generally increased over time, the fraction of

27

participants covered by those fully insured plans has moved in the opposite direction

(Figure 5 and Table 6). Indeed, small and large plans followed different patterns, as

demonstrated in this section.

Figure 12 shows the percentage of participants who were covered by a mixed-funded

or self-insured plan, by plan life cycle stage, from 2007 to 2016. It is the participant-

weighted counterpart of Figure 7. Mirroring the pattern among plans, participants in

new plans were generally less likely to be in mixed-funded or self-insured plans than

those in established plans. However unlike in Figure 7, participants in plans that

ceased filing were also less likely to be in mixed-funded or self-insured plans than

those in established plans, pointing at funding mechanism switching as the main

cause of the general upward trend in self-insurance among participants.

Figure 12. Participant-Weighted Percentage Mixed-Funded or Self-Insured

among New Plans, Established Plans, and Plans That Ceased Filing, by

Statistical Year

Before turning to switching patterns, consider that most participants are covered by

large plans (Table 1 and Table 8).

32

We restrict the analysis to the most recent five

years (2012-2016). Only about 1% of new plans covered 5,000 or more participants,

but those plans accounted for 45% of participants in all new plans. Among

established plans, 65% of participants were in plans with 5,000 or more participants.

32

Table 8 shows that 1.1% of new plans in 2012-2016 had 5,000 or more

participants. A manual review indicated that such plans commonly were successor

plans to prior plans that were replaced or consolidated, such as after a corporate

merger. Likewise, many plans that ceased filing may have been replaced with other

plans and secured continuing health benefit coverage for their participants.

28

The behavior of plans with more than 5,000 participants is therefore key to

understanding participant-weighted trends in funding.

Table 8. Distribution of Health Plans and Plan Participants, by Plan

Participant Counts (2012-2016)

Participants New Plans Established Plans

Plans That Ceased Filing

in plan (EOY) Plans Participants Plans Participants Plans Participants

Zero 3.1% 0.0% 0.4% 0.0% 33.7% 0.0%

1-99 14.7% 1.3% 8.2% 0.3% 19.9% 2.6%

100-199 51.9% 14.9% 31.0% 3.2% 20.9% 6.9%

200-499 19.6% 12.3% 31.5% 6.9% 14.8% 10.6%

500-999 5.1% 7.5% 12.3% 6.1% 5.1% 8.1%

1,000-1,999 2.6% 7.8% 7.3% 7.2% 2.8% 9.0%

2,000-4,999 1.8% 11.7% 5.2% 11.5% 1.7% 12.5%

5,000+ 1.1% 44.5% 4.1% 64.7% 1.0% 50.5%

Total 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% 100.0%

Source: Form 5500 health plan filings.

Note: Percentages may not sum to 100% because of rounding.

Table 9 shows the annual rate of funding mechanism switching among new and

established plans. Overall, 6.9% of plans that started as fully insured switched to

mixed-funded or self-insured during their second reporting period, but large plans

were much more likely to make that switch than small plans. For example, 27% of

fully insured new plans with 5,000 or more participants changed funding mechanism,

compared with less than 8% of plans with 1-500 participants. Conversely, small

plans that started life as mixed-funded or self-insured were more likely to switch to

fully insured than their larger counterparts. A similar pattern existed among

established plans. Since most participants are in large plans, the implication is that,

on net, participants in both new and established plans migrated to mixed-funded or

self-insured plans.

Table 9. Annual Rates of Funding Switching among New and Established

Plans, by Plan Size (2012-2016)

New Plans Established Plans

Swit

ch to Switch to

EOY plan

mixed or self-

Switch to

mixed or self-

Switch to

participants insured fully insured insured fully insured

Zero 10.3% 4.7% 12.0% 8.4%

1-99 6.9% 3.2% 5.9% 3.0%

100-199 5.3% 10.8% 4.6% 7.1%

200-499 7.6% 10.0% 6.3% 4.9%

500-999 11.7% 6.2% 10.0% 3.3%

1,000-1,999 13.8% 6.5% 12.9% 2.3%

2,000-4,999 22.6% 2.6% 17.6% 1.6%

5,000+ 26.7% 4.0% 18.0% 1.5%

All 6.9% 7.1% 6.7% 4.2%

Source: Form 5500 health plan filings.

Not

e: Rates are conditional on the appropriate universe. For example,

the denominator for the first column is fully insured new plans.

29

Rates at which plans ceased filing also varied by plan size (Table 10), with small

plans much more likely to stop filing in 2012-2016 than large plans.

33

Among plans

with 5,000 or more participants, fully insured plans ceased filing at a higher rate

than mixed-funded or self-insured plans.

Table 10. Annual Rates at Which New and Established Plans Ceased Filing,

by Plan Size (2012-2016)

New Plans Established Plans

BOY plan Mixed or Mixed or

participants self-insured

Ful

ly insured

self-insured Ful

ly insured

Zero 84.1% 80.0% 43.8% 38.2%

1-99 37.2% 29.8% 16.3% 18.8%

100-199 18.6% 15.0% 10.6% 9.6%

200-499 13.3% 10.2% 6.9% 6.9%

500-999 15.1% 10.7% 6.7% 6.3%

1,000-1,999 10.4% 11.5% 5.8% 6.5%

2,000-4,999 4.9% 6.1% 5.1% 6.0%

5,000+ 3.9% 13.9% 3.8% 6.0%

All 22.6% 15.0% 8.4% 8.6%

Source: Form 5500 health plan filings.

In conclusion, large plans on net switched away from full insurance, thereby

increasing the fraction of participants in mixed-funded or self-insured plans. Further

reinforcing this trend, large fully insured plans were more likely to cease filing than

large mixed-funded or self-insured plans. Despite these forces, mixed funding and

self-insurance retreated among participants, from 83% in 2015 to 82% in 2016

(Table 6). As discussed on page 17, this change is related to three very large travel

insurance plans that were fully insured and new to the analysis in 2016.

34

33

Given the focus on the end of the life cycle, Table 10 categorizes plans by the

number of participants at the beginning (rather than the end) of the reporting

period. On a related point, fully insured plans with zero or 1-99 participants generally

do not need to file, which may explain their high cease-filing rates. (Recall that

voluntary filings are included in the current section in order to observe as much as

possible of their life cycle; voluntary filings are excluded from the analysis in other

sections.)

34

As noted earlier, the life cycle analysis defines new plans as plans that checked the

“first return/report” box on the Form 5500. Only one of the three newly included

travel insurance plans checked that box in 2016. The other two checked it in 2015

but were excluded from the 2015 analysis because they did not indicate providing

health benefits at that time.

30

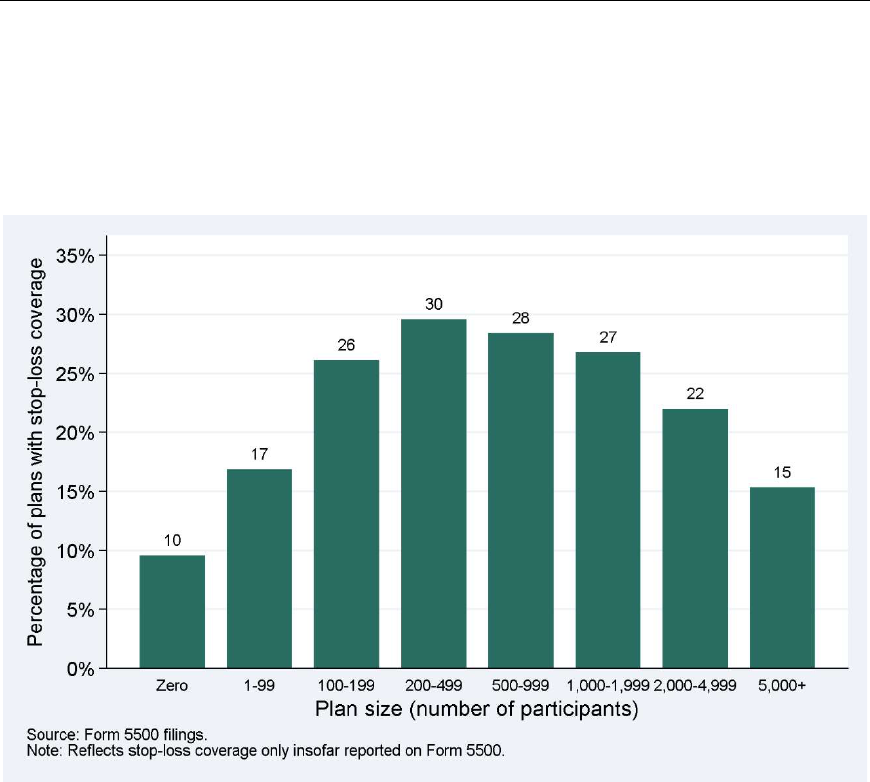

Stop-Loss Coverage of Plans

Table 11 examines the presence of stop-loss insurance. These figures must be

interpreted with caution. If stop-loss insurance identifies the health plan as the

beneficiary or it is purchased with plan assets, it must be reported on a Schedule A.

35

However, if the employer/sponsor has purchased stop-loss insurance with itself as

the beneficiary (rather than the plan), then it need not be reported on the Form

5500. The figures in Schedule A (and Table 11) thus likely understate the prevalence

of stop-loss insurance.

36

In 2016, 17% of mixed-funded and 25% of self-insured

plans reported stop-loss coverage in a Schedule A, down from 2007 rates of 24%

and 30%, respectively. The trend in reported stop-loss coverage of mixed-funded

plans was downward until 2014 and appears to have reversed since then.

Conversely, the trend among self-insured plans—downward until 2010 and fairly

stable until 2015—resumed its downward direction in 2016. Weighted by the number

of participants, approximately 15% of mixed-funded and 20% of self-insured plans

reported stop-loss coverage for 2016, indicating that smaller plans are more likely to

report stop-loss insurance than larger plans. We note that the participant-weighted

figures are historically more volatile than unweighted figures.

37,38

35

Schedule A is not required to be attached to the Form 5500-SF. Our analysis

assumes that none of the Form 5500-SF (1,508 of 23,704 self-insured plans, or 6%)

filers have stop-loss insurance.

36

Our 2012 report, Anomalies in Form 5500 Filings: Lessons from Supplemental

Data for Group Health Plan Funding, suggests that as many as four-out-of-five self-

insured or mixed-funded plans and roughly 55% of participants in such plans were

covered by stop-loss insurance, possibly purchased for the benefit of the plan

sponsor. Those stop-loss coverage levels are consistent with those in the 2013

KFF/HRET study, which found that 59% of participants in self-funded plans at firms

with 200 or more workers were in a plan that had purchased stop-loss insurance in

2013. See https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/report/2013-employer-health-

benefits. It should also be noted that reported stop-loss insurance does not

necessarily relate to health benefits but could protect other self-insured benefits,

such as disability benefits.

37