Brigham Young University Brigham Young University

BYU ScholarsArchive BYU ScholarsArchive

Faculty Publications

2010

Compatibility or Restraint? The Effects of Sexual Timing on Compatibility or Restraint? The Effects of Sexual Timing on

Marriage Relationships Marriage Relationships

Dean M. Busby

Brigham Young University - Provo

Jason S. Carroll

Brigham Young University - Provo

Brian J. Willoughby

Brigham Young University - Provo

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub

Part of the Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons

Original Publication Citation Original Publication Citation

Busby, D. M., Carroll, J. S., & Willoughby, B. J. (2010). Compatibility or Restraint?: The Effects of

Sexual Timing on Marriage Relationships. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 766-774.

BYU ScholarsArchive Citation BYU ScholarsArchive Citation

Busby, Dean M.; Carroll, Jason S.; and Willoughby, Brian J., "Compatibility or Restraint? The Effects of

Sexual Timing on Marriage Relationships" (2010).

Faculty Publications

. 4349.

https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/4349

This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been

accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more

information, please contact [email protected].

Compatibility or Restraint? The Effects of Sexual Timing on

Marriage Relationships

Dean M. Busby, Jason S. Carroll, and Brian J. Willoughby

Brigham Young University

Very little is known about the influence of sexual timing on relationship outcomes. Is it better

to test sexual compatibility as early as possible or show sexual restraint so that other areas of

the relationship can develop? In this study, we explore this question with a sample of 2035

married individuals by examining how soon they became sexually involved as a couple and

how this timing is related to their current sexual quality, relationship communication, and

relationship satisfaction and perceived stability. Both structural equation and group compar-

ison analyses demonstrated that sexual restraint was associated with better relationship

outcomes, even when controlling for education, the number of sexual partners, religiosity,

and relationship length.

Keywords: sexual timing, sexual quality, couple relationships, communication

Premarital sex has become a normative part of couple

formation in the United States and other modern societies

(Laumann, Gagnon, Michaels, & Michaels, 1994). Several

researchers have reported that approximately 85% of Amer-

icans approve of sexual relations prior to marriage and equal

numbers of both men and women report that they have had

premarital sex (Christopher & Sprecher, 2000; Kaestle &

Halpern, 2007). Although sexual relations are a part of the

contemporary dating script for the majority of couples, there

is evidence that couples differ in the pace and timing with

which they initiate sex in their relationships. Analyses using

data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent

Health (Add Health) study show that approximately 50% of

premarital young adult couples become sexually involved

within the first month of dating, while 25% initiate sex one

to three months after beginning to date and a small propor-

tion of couples wait until marriage before initiating sexual

relations (Sassler & Kamp Dush, 2009). Despite evidence

that couples vary in sexual timing trajectories, very little

research has examined how the timing of sexual relations in

a couple’s formation history influences the development of

other aspects of the relationship, as well as couple out-

comes. In particular, little is known about how sexual tim-

ing patterns may influence the relationships of couples who

stay together and eventually transition to marriage. The

purpose of this article is to explore the understudied link

between sexual timing patterns in coupling and later marital

outcomes.

Literature Review

Several family scholars studied the impact of premarital

sexual behavior on later marital outcomes, and found that

premarital sexuality was often a risk factor for later marital

instability (Kahn & London, 1991; Larson & Holman, 1994;

Teachman, 2003). These authors found that, while the very

fact of having sex before marriage was not usually linked to

lower subsequent marital satisfaction, certain characteristics

of premarital sexual activity, such as age at onset of sexual

debut and the number of partners, was negatively related to

the quality of marriage.

Sexuality during young adulthood has been studied more

as an individual status or condition rather than a sequenced

process in relationship development. One exception to this

was an early study published by Peplau, Rubin, and Hill

(1977). These scholars were the first to note that “research

on premarital sex has typically focused on attitudes and

experiences of individuals, rather than on sexual interaction

in couples” (p. 87). Utilizing what they called a “dyadic

approach” to studying premarital sex, these scholars con-

ducted a study with 231 college-aged dating couples to

examine links between the patterning of sexual behavior

and the development of love and commitment in dating

relationships. Peplau and colleagues (1977) used survey and

interview data to identify and compare three couple patterns

of sexual timing and commitment in dating relationships.

They labeled these groups “early sex” couples (couples who

had sexual intercourse within 1 month of their first date);

“later sex” couples (couples who had sex 1 month or later in

their dating); and “abstaining” couples (couples who were

abstaining from sexual intercourse until they were married).

These scholars noted that these three groups were consistent

Dean M. Busby, Jason, S. Carroll, and Brian J. Willoughby,

School of Family Life, Brigham Young University.

This research was supported by research grants from the School

of Family Life and the Family Studies Center at Brigham Young

University.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to

Dean M. Busby, School of Family Life, Brigham Young University,

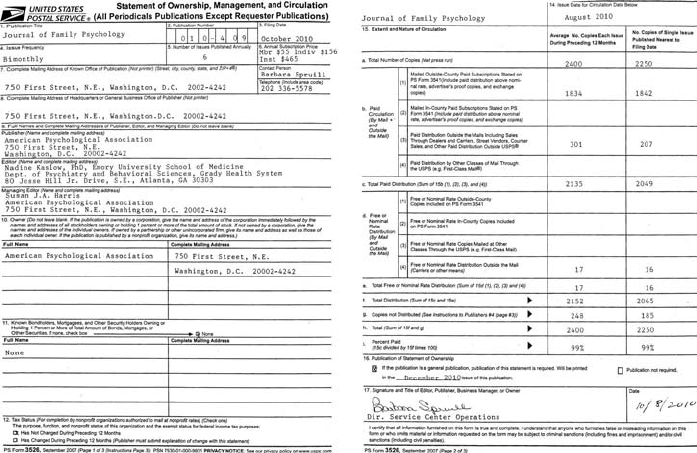

Journal of Family Psychology © 2010 American Psychological Association

2010, Vol. 24, No. 6, 766–774 0893-3200/10/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0021690

766

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

with the three sexual ethics groups presented by Reiss

(1960, 1967).

In later studies, other scholars began to look for ways to

conceptualize the affective and behavioral events, transi-

tions, or “turning points,” that people use as the interpreta-

tive signals of change in the commitment, intensity, defini-

tion, or stage of development in their romantic relationships

(e.g., Baxter & Bullis, 1986; Bullis, Clark, & Sline, 1993;

Huston, Surra, Fitzgerald, & Cate, 1981). Building upon the

early work of Bolton (1961); Baxter and Bullis (1986)

initiated their systemic investigations of relevant “turning

points” in relationship development. According to Baxter

and Bullis (1986), a turning point is “any event or occur-

rence that is associated with change in the relationship” (p.

470). In particular, these scholars identified the “passion

turning point” or markers of initial sexual involvement as

highly salient in dating couples’ relationships.

Utilizing the turning points perspective, Metts (2004)

hypothesized that the relative sequencing of commitment

and sexual involvement was a critical factor in couple

formation. Specifically, Metts noted that while sexual in-

volvement can and does occur with no prior expressions of

commitment, the passion turning point will be qualitatively

different for a couple when sexual involvement follows

after commitment rather than before. In a study of the

“passion turning point” in the dating relationships of 286

college students, Metts (2004) analyzed the relative se-

quencing of expressions of love and commitment and the

timing of “first sex” in relationships. With regard to the

timing of sexual intimacy, Metts found that the length of

time dating prior to first sexual involvement was a negative

predictor of commitment in men, but not in women. How-

ever, Metts found that for both men and women, the explicit

expression of love and commitment prior to sexual involve-

ment in a dating relationship influenced the personal and

relational meaning of the event. Specifically, Metts (2004)

found that when higher levels of commitment were present,

sexual involvement was more likely to be perceived as a

positive turning point in the relationship, increasing under-

standing, commitment, trust, and a sense of security. How-

ever, when emotional expression and commitment did not

precede sexual involvement, the experience was signifi-

cantly more likely to be perceived as a negative turning

point, evoking regret, uncertainty, discomfort, and prompt-

ing apologies. Consequently, we propose that the timing of

sexual involvement will influence both the sexual quality of

the relationship and the development of communication

(understanding) within that relationship.

Focus of the Study

Although there are only a few studies that have empiri-

cally examined sexual timing patterns in couple relation-

ships, these studies, along with several theoretical ideas

presented in other published work, can be used to organize

an empirical and theoretical approach to the topic. Existing

perspectives of sexuality in relationship development offer

two differing paradigms on the impact of sexuality on

relationship formation—a sexual compatibility perspective

and a sexual restraint perspective.

Sexual compatibility vs. sexual restraint. The first theo-

retical perspective of couple sexuality could be referred to

as the sexual compatibility model, which holds that sexual

interaction is essential during the couple formation process

as it allows partners to assess their compatibility with one

another in this important domain of relationship function-

ing. This line of reasoning is predominant in popular think-

ing about romantic relationship formation as the topic of

“sexual chemistry” is frequently emphasized as an impor-

tant relationship characteristic for young people to both test

and seek out in romantic relationships, particularly in a

relationship that may lead to marriage (Cassell, 2008).

Among scholars and clinicians, sexual chemistry has been

defined as a “mysterious, physical, emotional, and sexual

state” that when present in a relationship creates something

“unique and explosive” (Leiblum & Brezsnyak, 2006,

p. 55).

When the concepts of sexual chemistry and compatibility

are applied to premarital relationships, the generally ac-

cepted notion is that sexual involvement fosters emotional

closeness in the early months of dating, as well as providing

opportunities for self-discovery that may lead to greater

feelings of self-worth. From this perspective, individuals

and couples who do not test their sexual chemistry prior to

the commitments of exclusivity and later marriage are seen

as being at risk for entering into a relationship that will not

satisfy them in the future – thus increasing their risk of

marital distress and failure (Cassell, 2008).

Despite the acceptance and practice of testing sexual

compatibility for many people, there are several areas of

theoretical development that suggest that early sexual initi-

ation may be detrimental to couple formation processes and

later marital outcomes. Contrary to perspectives of sexual

compatibility, a sexual restraint model holds that sexual

involvement during couple formation processes, particu-

larly in the early stages, may be detrimental to overall

relationship development. In particular, the relative se-

quencing of sexual behavior, relationship commitment (i.e.,

sex precedes commitment vs. commitment precedes sex),

and attachment has been hypothesized to be a critical factor

in determining how sexual initiation may impact overall

couple development (Metts, 2004). A conceptual model of

sexual restraint suggests that couples who delay or abstain

from sexual intimacy during early couple formation allow

communication and other social processes to become the

foundation of their attraction to each other, a developmental

difference that may become critical as couples move past an

initial period of sexual attraction and excitement into a

relationship more characterized by companionship and part-

nership. Early sex may increase the risk for asymmetrical

commitment levels, less developed communication patterns,

more constraint to leaving the relationship, less sexual sat-

isfaction later in the relationship, and less ability to manage

adversity and conflict (Stanley, Rhodes, & Markman, 2006).

Although there is theoretical literature on both perspec-

tives, there is little empirical examination of either. The

767SEXUAL TIMING AND MARRIAGE

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

focus of the current study was to examine whether data

evaluating the timing and influence of sexuality supports

one or the other perspective.

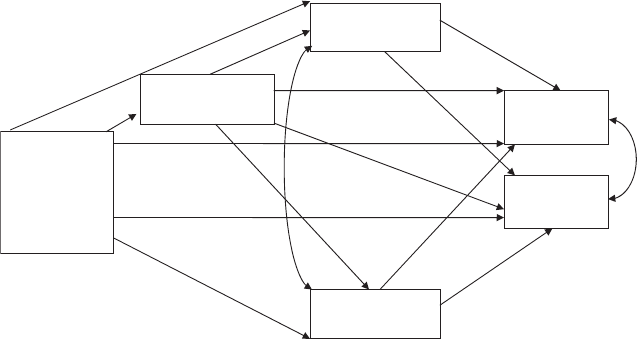

Research Questions

How is sexual timing related to couple processes and

outcomes? Based on the literature and theory previously

reviewed, we developed a structural model illustrated in

Figure 1 that describes how sexual timing might influence

relationship outcomes. As seen in the model, we propose

that sexual timing will influence both the sexual quality of

a relationship and the communication expressed in the re-

lationship and that all of these variables will influence

relationship satisfaction and perceived stability. Both sexual

quality and communication have been linked together and to

relationship satisfaction in previous research (Christopher &

Sprecher, 2001) and the link between sexual timing and

different levels of sexual quality and communication has

been suggested by Metts (2004). We include relationship

length, religiosity, the number of sexual partners, race,

education, income, and parents’ divorce as control variables

in this study. Existing research demonstrates that satisfac-

tion changes over time in relationships, religiosity has been

linked to decisions of when to express sexuality in relation-

ships, while race, education, and income have been linked to

different sexual attitudes and behaviors (Bradbury & Kar-

ney, 2004; Christopher & Sprecher, 2001; Sprecher &

McKinney, 1991). By using these variables as controls, we

will be able to discuss the influence of sexual timing over

and above the influence of the control variables. Finally,

gender is likely to influence many of the variables in the

model so we evaluated whether the path coefficients were

significantly different for males and females (Kaestle &

Halpern, 2007).

If the sexual compatibility idea is valid we would expect

that delayed sexual timing would be negatively related to

sexual quality and communication as well as relationship

satisfaction and perceived stability. This means that the

longer a person waited to be sexual in the relationship the

worse would be their sexual quality, communication, satis-

faction, and perceived stability in marriage. At the least, we

would expect the relationship between sexual timing and the

other variables to be insignificant. On the other hand, if the

sexual restraint idea is valid we would expect that the longer

a person waited to become sexual in their relationship, the

better the outcomes.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

The sample from this study was drawn from the entire

population of participants who completed the Relationship

Evaluation Questionnaire (RELATE: Busby, Holman, &

Taniguchi, 2001) between 2006 and 2009. All participants

completed an appropriate consent form prior to the comple-

tion of the RELATE instrument and all data collection

procedures were approved by the institutional review board

at the authors’ university. Individuals completed RELATE

online after being exposed to the instrument through a

variety of sources. Twenty-nine percent of the sample were

referred to the online site by their instructor in a class, 25%

were directed to the site by a relationship educator or

therapist, 8% were sent to the site by clergy, 18% were

referred to the site by a friend or family member, 7% were

referred by an ad the saw online or in a print, and the

remaining 13% of the participants found the instrument by

searching for it on the web.

The RELATE sample included many individuals in a

variety of relationship types from early acquaintances who

were just starting to date to seasoned marriages. Because of

the sexual timing and other relationship variables that were

analyzed in this study, the only individuals retained in the

sample were participants in a heterosexual relationship that

was their first marriage. This resulted in a sample of 2,035

individuals.

Seventy-seven percent of the sample was Caucasian, 7%

African American, 6% Latino, 6% Asian, and 4% listed

“Other.” In terms of education, 8% completed a high school

Control Variables:

Religiosity

Rel. Length

# Sexual Partners

Race

Income

Education

Parents’ Divorce

Sexual Timing

Sexual Quality

Communication

Perceived

Stability

Satisfaction

Figure 1. Initial model of the hypothesized association of sexual timing on relationship outcomes.

768 BUSBY, CARROLL, AND WILLOUGHBY

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

diploma or less as their highest degree of education, 32%

completed some college, 24% completed a bachelor’s de-

gree, 10% completed some graduate schooling, and 26%

completed a graduate degree. The mean age of the respon-

dents was 36.1 with a standard deviation of 10.2 and a range

from 19 to 71. The measure of relationship length indicated

that 9% of the couples had been married for six months or

less, 11% between 6 and 12 months, 21% for 1–2 years,

19% for 3–5 years, 15% for 6–10 years, 14% for 11-20

years, and 11% for more than 20 years.

In terms of religious affiliation, 21% of the respondents

were Catholic, 39% were Protestant, 6% were Latter-Day

Saints (Mormon), 17% were members of “another religion,”

and 17% were not affiliated with any religion. These reli-

gious affiliations indicated that there were differences be-

tween the sample in this study and national norms (U.S.

Religious Landscape Survey, 2007). There were fewer Prot-

estants and Catholics (11% fewer Protestants, 3% fewer

Catholics), and more people in the Mormon (4% more),

another religion (12% more, largely because we had fewer

available categories to choose from), and unaffiliated

groups (1% more).

Measures

The RELATE is an approximately 300-item online ques-

tionnaire designed to evaluate the relationship of individuals

in a dating, engaged, or married relationship. The questions

examine several different contexts—individual, cultural,

family (of origin), and couple—in order to provide a com-

prehensive evaluation of challenges and strengths in their

relationships.

Previous research has documented RELATE’s reliability

and validity, including test-retest and internal consistency

reliability; and content, construct, and concurrent validity

(Busby et al., 2001). We refer the reader specifically to

Busby et al.’s (2001) discussion of the RELATE for detailed

information regarding the theory underlying the instrument

and its psychometric properties. The scores for participants

on all the scales in this study were mean scores when more

than one question was combined. Except for the questions

on the frequency of sexual behavior, and the control vari-

ables, questions were answered using 5-point Likert re-

sponse choices.

Sexual timing variable. This variable was one item that

asked individuals how soon they had sexual relations with

their current partner. Although the term “sexual relations” is

more general and less precise than sexual intercourse, this

term was selected because couples are known to engage in

a variety of sexually intimate behaviors other than sexual

intercourse, such as oral sex, and the research to date does

not indicate one type of sexual behavior has a different

influence on relationships than other types (Christopher &

Sprecher, 2001; Regnerus, 2007). Also the existing research

indicates that most individuals consider all of these types of

behaviors as “sex” (Regnerus, 2007). The frequencies on

this variable are presented in Table 1.

Sexual quality variable. The Sexual Quality scale con-

sisted of three questions about the sexual relationship; how

satisfied participants were with their sexual intimacy, how

often sex was a problem in their relationship and how

frequently they had sex with their partners. All variables

were coded in such a way that higher values were equivalent

to higher sexual quality. The internal consistency reliability

coefficient for the Sexual Quality scale was .79.

Communication variable. The Communication scale

consisted of 14 items evaluating how well participants were

able to express empathy and understanding to their partners,

how well they were able to send clear messages to their

partner, how often they were prone to be critical, and how

often they were prone to defensive communication. All

items were coded so that a higher value was equivalent to

better communication. The internal consistency reliability

coefficient for the Communication scale was .86. In terms of

test-retest and validity information on this scale, the com-

munication items have been shown to have test-retest values

between .70 and .83 and were appropriately correlated with

a version of a commonly used Relationship Quality measure

as predicted (Busby et al., 2001). Also these scales have

been shown in longitudinal research to be predictive of

couple outcomes and are amenable to change in couple

intervention studies that focus on communication (Busby,

Ivey, Harris, & Ates, 2007).

Relationship satisfaction variable. This scale consisted of

questions about how satisfied participants were with five

different areas including the time they spent together, the

love they experienced, the way conflict was resolved, the

amount of relationship equality they experienced, and sat-

isfaction with their overall relationship. The internal con-

sistency reliability coefficient for the Relationship Satisfac-

tion scale was .89. Additional test-retest reliability estimates

in past research were between .76 and .78 (Busby et al.

2001). Validity data have also shown the strength of this

scale indicating that it is highly correlated with the existing

relationship quality and satisfaction measures both in cross-

sectional and longitudinal research (Busby et al., 2001,

2007).

Table 1

Number of Participants (N ⫽ 2097) Who Initiated Sexual

Timing at Specific Times in Their Relationship

Timing of sexual involvement with current partner

Number of

Participants

1. We had sexual relations before we started dating 126

2. We had sexual relations on our first date 172

3. We had sexual relations a few weeks after we

started dating 478

4. We had sexual relations from 1 to 2 months

after we started dating 389

5. We had sexual relations from 3 to 5 months

after we started dating 248

6. We had sexual relations from 6 to 12 months

after we started dating 170

7. We had sexual relations from 1 to 2 years after

we started dating 71

8. We had sexual relations more than 2 years after

we started dating 45

9. We had sexual relations only after we married 336

769SEXUAL TIMING AND MARRIAGE

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Perceived relationship stability variable. This scale con-

sisted of three questions that asked respondents how often

they thought their relationship was in trouble, how often

they thought of ending the relationship, and how often they

had broken up and gotten back together, with higher scores

indicating greater relationship stability. These items were

adapted from earlier work by Booth, Johnson, & Edwards

(1983). The internal consistency reliability coefficient with

this sample for the Perceived Stability scale was .77. Pre-

vious studies have shown this scale to have test-retest reli-

ability values between .78 and .86, to be appropriately

correlated with other relationship quality measures, and to

be valid for use in cross-sectional and longitudinal research

(Busby et al., 2001, 2007; Busby, Holman, & Neihuis,

2009).

Control variables. Since we knew from the demographic

variable frequencies that all but seventeen percent of the

sample was affiliated with a religious organization, and we

suspected that religiosity was substantially related to

whether respondents delayed their sexual involvement in

their relationship, we controlled for religiosity in our anal-

yses. The Religiosity scale consisted of three questions that

evaluated how often respondents attended church, how of-

ten they prayed, and how often spirituality was an important

part of their life. The internal consistency reliability coef-

ficient for the Religiosity scale was .89. Additional research

has shown this scale to have test-retest reliability scores of

.86 to .88 (Busby et al, 2001).

Relationship Length was also used as a continuous con-

trol variable in this study. Individuals were asked to indicate

how long they had been in a relationship with their partners.

Responses ranged from 6 months or less to more than 30

years. However, it may be that there are certain cohort and

survival effects in the sample such that those who were

married for longer periods of time were those more likely to

have had sex later in their relationship and to stay together.

To explore this possibility we divided the sample into two

groups comparing those in shorter term marriages (less than

10 years) to those in longer-term marriages. When we split

the sample in this way and reran our analyses we did not

find these two groups to be significantly different on the

sexual timing variable. We also did not find the multivariate

analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) and the structural

equation model (SEM) results to be substantial different for

those we report in the forthcoming results section, conse-

quently we used Relationship Length as a continuous vari-

able in our analyses.

Income, education, and race were also used as control

variables and were single item demographic variables. Race

was dummy-coded with Caucasian’s as the reference group.

We also used a dichotomous yes/no variable of parents’

divorce, and the number of sexual partners reported by the

participants as control variables.

We suspected that many of the control variables were not

significantly related to the relationship outcomes (sexual

quality, communication, relationship satisfaction, or per-

ceived relationship stability) in this study so we conducted

preliminary multiple regression analyses to explore which

control variables should be retained in the analysis of the

model in Figure 1. The only control variables that had a

significant influence on at least one of these couple out-

comes were religiosity, relationship length, the number of

sexual partners, and education. These variables were re-

tained and included in the SEM analysis and the group

comparisons reported in the results section.

Results

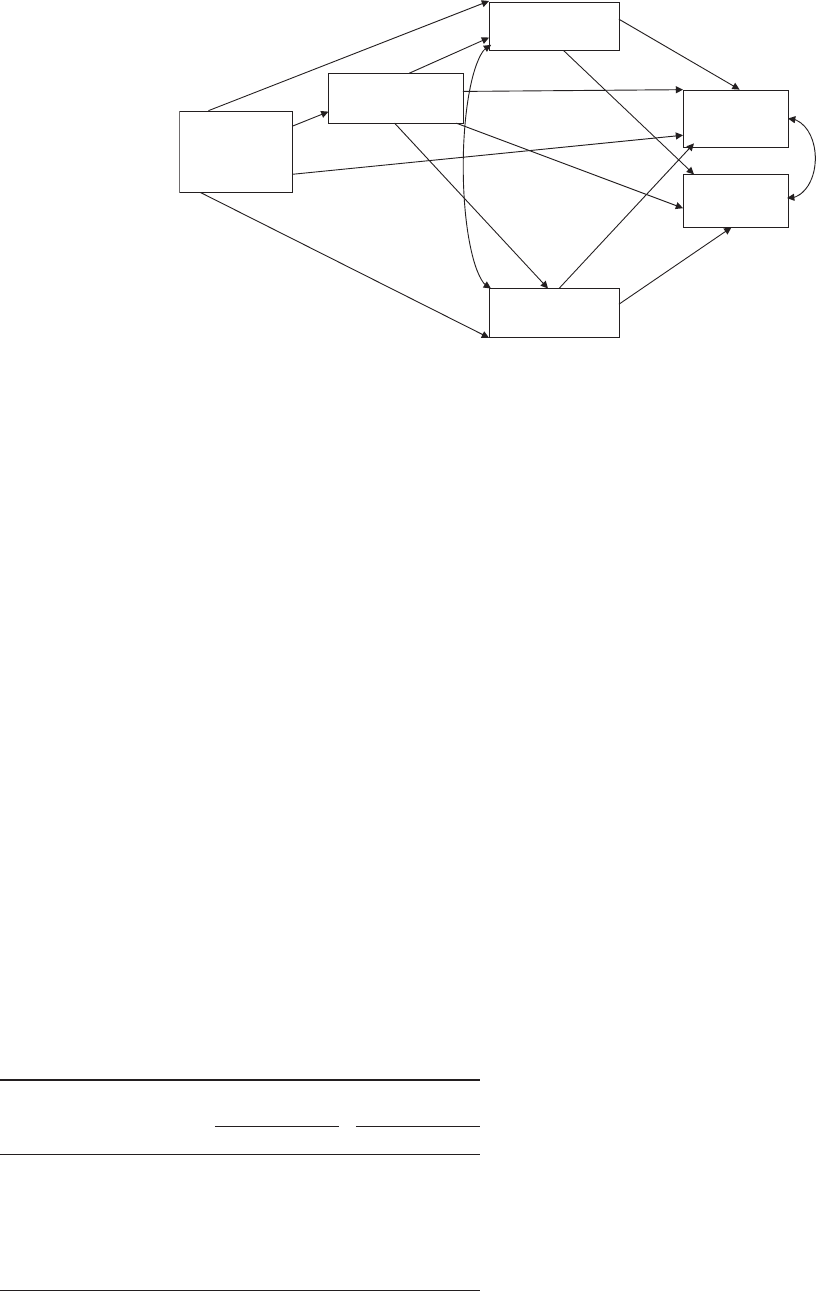

The evaluation of the model in Figure 1 was conducted

with AMOS version 7.0 (Arbuckle, 2006). Although error

terms were included for each of the endogenous variables

listed in the Figure, they were not drawn into the SEM

models to simplify the figures.

We report several fit measures to assist in the evaluation

of how well our hypothesized model replicates the sample

data. We follow the recommendations of McDonald and Ho

(2002) and Kline (2005) to report both absolute fit indexes

and incremental fit indexes.

The analysis of the model presented in Figure 1 for the

whole sample indicated that the model was an excellent fit

to the data. The sample size for the SEM analysis was 2035.

The chi-square with 9 degrees of freedom was 15.68 and

was not significant (p ⫽ .074), the Tucker Lewis Index

(TLI) was .99, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was, .99,

while the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

(RMSEA) was .02.

Comparing Males and Females

The chi-square difference value for the constrained and

unconstrained models comparing female and male partici-

pants with 14 degrees of freedom was 102.96 and was

significant (p ⬍ .001), indicating that the structural model

was not equivalent for the two groups. However upon

exploring the specific coefficients that were significantly

different for males and females the only ones were the

control variables of the number of sexual partners, educa-

tion, and religion on sexual timing and sexual quality. In

each instance the coefficients were larger for males than

they were for females. Even these differences were small to

moderate in the range of .07 to .15 larger for males than for

females. None of the coefficients listed in Figure 2 were

significantly different for males and females.

Figure 2 shows the standardized path coefficients for the

variables in the model for females and males excluding the

specific coefficients for the control variables. The influence

of the control variables on the major couple outcomes was

weak with none of the control variables having a direct

influence on relationship satisfaction and only education

and the number of sexual partners having an effect of .05

and .07 on perceived relationship stability. Religiosity and

relationship length had a significant effect on sexual quality

of .05 and ⫺.17 respectively. Education, religiosity, and

relationship length had an effect of .10, .10, and .08 on

communication. The strongest effects of the control vari-

ables were on sexual timing with religiosity having an effect

770 BUSBY, CARROLL, AND WILLOUGHBY

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

of .33 and the number of sexual partners having an effect of

⫺.36.

The squared multiple correlations for the endogenous

variables in the model demonstrated that the variables ex-

plained large percentages of variance for Sexual Timing,

Perceived Stability, and Satisfaction.

The total effects of each variable in the model on Rela-

tionship Satisfaction and Perceived Stability are presented

in Table 2. These effects showed that the variables with the

strongest association with Satisfaction were Communica-

tion and Sexual Quality for both females and males. The

variables with the strongest total effects on Perceived Sta-

bility were Communication and Sexual Timing.

Group Comparisons

The significant paths in the model lead us to conduct

group comparisons to explore how people who displayed

varied periods of sexual timing in their relationship might

have unique patterns of Communication, Sexual Quality,

Satisfaction, and Perceived Stability. Based on the theory

we presented in the introductory section and building on the

work of Peplau and colleagues (1977) we divided the sam-

ple into three groups, those who were sexual with their

married partner from before they started dating to less than

one month after they started dating (labeled as “Early Sex”

by Peplau et al., 1977), those who were sexual with their

partners between 1 month and 2 years after they started

dating (labeled as “Later Sex” by Peplau et al., 1977), and

those who were only sexual with their partners after mar-

riage (labeled as “Abstaining” by Peplau et al, 1977).

To compare these three groups we conducted a Multivar-

iate Analysis of Covariance; an analysis particularly appro-

priate for comparing groups of participants on correlated

dependent variables with several control variables. The in-

dependent variables were the Sexual Timing Group and

Gender, with the dependent variables being Communica-

tion, Sexual Quality, Satisfaction, and Perceived Stability.

The control variables were Religiosity, Relationship

Length, Education, and the Number of Sexual Partners.

The results from the MANCOVA indicated that Sexual

Timing Group and Gender had a significant effect on the

dependent variables while holding the control variables

constant. The multivariate F-test for Sexual Timing Group

was significant, Wilks’s ⌳⫽.96, F(8, 3812) ⫽ 11.01, p ⬍

.001. The multivariate F-test for Gender was significant,

Wilks’s ⌳⫽.99, F(4, 1906) ⫽ 5.17, p ⬍ .001. The

covariates were significantly related to the outcome mea-

sures at p ⬍ .001. The multivariate F-test for the interaction

between Sexual Timing Group and Gender was not signif-

icant, Wilks’s ⌳⫽.99, F(8, 3812) ⫽ 0.72, p ⫽ .676.

Since the multivariate tests were significant for the two

independent variables, it was appropriate to consider the

univariate results. To evaluate the effect sizes of the inde-

pendent variables on the dependent variables the partial eta

squared statistic (

2

) was used. The univariate F-test asso-

ciated with Sexual Timing Group was significant for the

dependent variable Communication, F(2, 1919) ⫽ 21.80,

p ⬍ .001, partial

2

⫽ .02; for the dependent variable

Sexual Quality F(2, 1919) ⫽ 12.10, p ⬍ .001, partial

2

⫽

.01; for the dependent variable Relationship Satisfaction

F(2, 1919) ⫽ 20.94, p ⬍ .001, partial

2

⫽ .02; and for the

Sexual Timing

Sexual Quality

Communication

Perceived

Stability

Satisfaction

.14* (.14)*

.15* (.20)*

.24* (.21)*

.52* (.49)*

.40*

(

.36

)

*

.08* (.13)*

.39* (.42)*

.02 (.05)*

.46* (.47)*

.44* (.40)*

R

2

=.43 (.43)

R

2

=.63 (.61)

R

2

=.07 (.07)

R

2

=.06 (.07)

R

2

=.29 (.28)

Control Variables:

Religiosity

Rel. Length

# Sexual Partners

Education

Figure 2. The final model showing the influence of sexual timing on relationship outcomes for

females and males (in parenthesis).

Table 2

Standardized Total Effects of the Variables in the Model

on Perceived Relationship Stability and Relationship

Satisfaction for Females and Males

Variable

Relationship

satisfaction

Perceived

stability

Females Males Females Males

Religiosity .16 .16 .16 .18

Relationship length ⫺.11 ⫺.09 ⫺.11 ⫺.04

Education .02 .02 .05 .04

Number of sexual partners ⫺.05 ⫺.04 ⫺.12 ⫺.12

Sexual timing .15 .21 .22 .28

Communication .52 .49 .47 .48

Sexual quality .40 .38 .23 .16

771SEXUAL TIMING AND MARRIAGE

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

dependent variable Perceived Relationship Stability F(2,

1919) ⫽ 40.05, p ⬍ .001, partial

2

⫽ .04.

The univariate F-test associated with Gender was signif-

icant for the dependent variable Communication, F(1,

1919) ⫽ 5.03, p ⬍ .05, partial

2

⫽ .003; for the dependent

variable Relationship Satisfaction F(1, 1919) ⫽ 9.33, p ⬍

.01, partial

2

⫽ .005; and for the dependent variable

Perceived Relationship Stability F(1, 1919) ⫽ 12.32, p ⬍

.001, partial

2

⫽ .006. The univariate F-test associated

with Gender was not significant for the dependent variable

Sexual Quality F(1, 1919) ⫽ .03, p ⫽ .877, partial

2

⫽

.000.

With significant multivariate and univariate F-tests the

next step was to explore the specific differences between

each sexual timing group on the dependent variables

through step-down F-Tests, using the Bonferroni method to

control for multiple comparisons. The means and standard

deviations for the three sexual timing groups and gender on

the four dependent variables are presented in Table 3. The

means in Table 3 demonstrate that the Sexual Timing Group

that participants belonged to had the strongest association

with Perceived Relationship Stability and Satisfaction as all

three groups were significantly different from each other. In

other words, the longer participants waited to be sexual, the

more stable and satisfying their relationships were once they

were married. Gender had a relatively small influence on the

dependent variables. For the other dependent variables, the

participants who waited to be sexual until after marriage had

significantly higher levels of communication and sexual

quality compared to the other two sexual timing groups.

Discussion

For many individuals, sexual involvement in the early

stages of dating is seen as an important part of testing

relationship compatibility and determining if the relation-

ship should proceed toward deeper levels of commitment.

The conventional wisdom in the current dating culture is

that couples should test their “sexual chemistry” before

moving to deeper stages of commitment. The prevailing

perspective is that romantic involvement during emerging

adulthood provides an opportunity for individuals to explore

their sexuality in the context of their feelings of love for and

perceptions of being loved by their partner. If this theory is

correct, sexual restraint during couple formation should be

negatively correlated with later relationship outcomes for

couples who decide to marry. The results of this study do

not support this theory. With the sample in this study it is

clear that the longer a couple waited to become sexually

involved the better their sexual quality, relationship com-

munication, relationship satisfaction, and perceived rela-

tionship stability was in marriage, even when controlling for

a variety of other variables such as the number of sexual

partners, education, religiosity, and relationship length.

One explanation for these results is the sexual restraint

theory presented in the introduction section. It is likely that

two mechanisms are at work, underdeveloped relationships

and inertia. In regard to underdeveloped relationships, it is

possible that early sexual involvement focuses the relation-

ship more on physical and sexual aspects of both the partner

and the relationship and less on issues of communication

and commitment. The results that show that delayed sexual

timing is associated with increased quality of the commu-

nication and the sexual areas of the relationship, as well as

perceived relationship stability are consistent with this the-

ory. It is interesting that sexual timing is more strongly

related to communication than it is to sexual quality and

more strongly related to perceived relationship stability than

it is to relationship satisfaction. It may be that relationships

that are founded more on sexual rewards and pleasures early

on end up resulting in more fragile relationships in the

long-term. These findings are consistent with the research

and theory presented by Stanley and associates (Stanley &

Markman, 1992; Stanley et al., 2006) on their commitment

model of couple relationships. In general, commitment the-

ory makes a distinction between forces that motivate con-

nection, called dedication, versus forces that increase the

costs of leaving, called constraint.

Using these constructs, Stanley and Markman (1992)

propose a concept of couple formation that they call “rela-

tionship inertia.” The central idea of inertia is that some

couples who otherwise would not have married end up

married partly because they become “prematurely entan-

gled” (Glenn, 2002) in a relationship prior to making the

decision to be committed to one another. Inertia suggests

that it becomes harder for some couples to veer from the

path they are on, even when doing so would be wise (see

Stanley et al., 2006 for a full discussion of this theory and

related issues). Although research on cohabitation led to

Table 3

Means (Standard Deviations) for Females and Males in the Three Sexual Timing Groups on Communication, Sexual

Quality, Relationship Satisfaction, and Perceived Relationship Stability

Dependent

variable

1. Early sex 2. Later sex 3. Married sex

Females

(N ⫽ 413)

Males

(N ⫽ 333)

Females

(N ⫽ 524)

Males

(N ⫽ 371)

Females

(N ⫽ 179)

Males

(N ⫽ 150)

Communication 3.3 (.57) 3.4 (.54) 3.5

a

(.58) 3.5 (.54) 3.7

a

(.63) 3.8

a

(.55)

Sexual quality 3.5 (1.1) 3.4 (1.1) 3.5 (1.0) 3.5 (1.1) 4.0

a

(.98) 3.9

a

(.97)

Satisfaction 3.0

ⴱ

(1.1) 3.2 (.95) 3.2

a

(1.0) 3.3

a

(.94) 3.7

aⴱ

(1.1) 3.8

a

(.87)

Perceived stability 3.6 (.97) 3.7 (.90) 3.8

aⴱ

(.91) 3.9

a

(.84) 4.3

a

(.79) 4.4

a

(.62)

a

Significantly different than all other sexual timing groups of the same gender.

ⴱ

Significantly different than the males in the same group.

772 BUSBY, CARROLL, AND WILLOUGHBY

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Stanley and Markman’s (1992) development of the concept

of relationship inertia, they proposed that similar conse-

quences are possible when couples “slide” into couple tran-

sitions, such as sexual involvement, without deliberate

choice and commitment.

The primary focus here is that when people slide through

major relationship transitions the decreased level of delib-

eration may lower the odds of pro-relational behaviors.

Furthermore, sexual involvement without clear commitment

can represent an ambiguous state of commitment for many

partners. The ambiguity of early sexual initiation may un-

dermine the ability of some couples to develop a clear and

mutual understanding about the nature of their relationships.

In contrast, commitment-based sexuality is more likely to

create a sense of security and clarity between partners and

within their social networks about exclusivity and a future.

The results from this study support these propositions.

Nevertheless, it is important to consider the limitations of

this study and the moderate effects in the model before

concluding that sexual compatibility is not supported. The

sample in this study is clearly not representative and con-

sists of a more educated, white population than a random

sample would have produced. Also the distribution of par-

ticipants into different religious denominations is not rep-

resentative of national norms. It is possible that the associ-

ations between sexual timing and relationship outcomes are

different with segments of the population that were under-

represented in this study. A longitudinal sample where

couples were asked about the meaning of their first sexual

involvement, regardless of the timing, would have resulted

in a clearer test of these theories than the sample we eval-

uated. It may be that some couples were not sliding into

sexual involvement, no matter how early or late it occurred

in their relationship. Longitudinal analyses would also pro-

vide a clearer test of the association between sexual timing

with actual relationship stability instead of the perceived

stability that we measured.

The strength of the associations of sexual timing with the

other variables in this study are moderate, and in the group

analysis are often small. Consequently to state that the

results indicate that people who engage in early sexual

relations are at great risk for relationship problems would be

an error. Clearly there are many other aspects of relationship

functioning that are not measured in our study. It may be

that other variables such as attachment and personality are

better explanations for the patterns in this study that should

be included in the future studies. However, the findings of

this study also suggest that to state that couples who delay

or abstain from sexual involvement prior to marriage are

disadvantaged or at greater risk for sexual and relationship

problems is also an error.

Nevertheless, authors studying sexuality have often at-

tributed the different patterns of sexual timing in relation-

ships to be primarily about religious values and culture

(Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994; Regnerus

2007). Because we have controlled for religiosity, we have

been able to demonstrate that sexual timing has a unique

effect beyond religious involvement. If the effect of sexual

timing is not just about religiosity, it may be more related to

concepts of poor mate selection, lower levels of commit-

ment to marriage, comparing partners with alternatives, and

normalizing breakups as discussed by several authors

(Kaestle & Halpern, 2007; Stanley et al, 2006; Teachman,

2003). Since in our study sexual timing had its strongest

relationship to communication, we speculate that the re-

wards of sexual involvement early on may undermine other

aspects of relationship development and evaluation such

that individuals may not put as much energy into crucial

couple processes such as communication and may stay with

partners who are not as skilled in these processes, thereby

resulting in a marriage that is more brittle. The significant

relationship between sexual timing and perceived relation-

ship stability in our results further supports these specula-

tions.

References

Arbuckle, J. L. (2006). Amos 7.0 user’s guide. Chicago, IL: SPSS.

Baxter, L. A., & Bullis, C. (1986). Turning points in developing

romantic relationships. Human Communication Research, 12,

469–493.

Bolton, C. D. (1961). Mate selection as the development of a

relationship. Marriage and Family Living, 23, 234–240.

Booth, A., Johnson, D. R., & Edwards, J. N. (1983). Measuring

marital instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45,

387–394.

Bradbury, T. N., & Karney, B. R. (2004). Understanding and

altering the longitudinal course of intimate partnerships. Journal

of Marriage and the Family, 61, 451–463.

Bullis, C., Clark, C., & Sline, R. (1993). From passion to com-

mitment: Turning points in romantic relationships. In P. Kalb-

fleisch (Ed.), Interpersonal communication: Evolving interper-

sonal relationships (pp. 213–236). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates.

Busby, D. M., Holman, T. B., & Niehuis, S. (2009). The associ-

ation between partner- and self-enhancement and relationship

quality outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 449–

464.

Busby, D. M., Holman, T. B., & Taniguchi, N. (2001). RELATE:

Relationship evaluation of the individual, family, cultural, and

couple contexts. Family Relations, 50, 308–316.

Busby, D. M., Ivey, D. C., Harris, S. M., & Ates, C. (2007).

Self-Directed, therapist-directed, and assessment-based interven-

tions for premarital couples. Family Relations, 56, 279–290.

Cassell, C. (2008). Put passion first: Why sexual chemistry is the

secret to finding and keeping lasting love. New York: McGraw-

Hill.

Christopher, F. S., & Sprecher, S. (2000). Sexuality in marriage,

dating, and other relationships: A decade review. Journal of

Marriage and Family, 62, 999–1017.

Glenn, N. D. (2002). A plea for greater concern about the quality

of marital matching. In A. J. Hawkins, L. D. Wardle, & D. O.

Coolidge (Eds.), Revitalizing the institution of marriage for the

twenty-first century: An agenda for strengthening marriage (pp.

45–58). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Huston, T. L., Surra, C., Fitzgerald, N. M., & Cate, R. (1981).

From courtship to marriage: Mate selection as an interpersonal

process. In S. Duck & R. Gilmour (Eds.), Personal relationships

2: Developing personal relationships (pp. 53–88). New York:

Academic Press.

Kaestle, C. E., & Halpern, C. T. (2007). What’s love got to do with

it? Sexual behaviors of opposite-sex couples through emerging

773SEXUAL TIMING AND MARRIAGE

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

adulthood. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 39,

134–140.

Kahn, J., & London, K. (1991). Premarital sex and the risk of

divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 845–855.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation

modeling. New York: Guilford.

Larson, J. H., & Holman, T. B. (1994). Premarital predictors of

marital quality and stability. Family Relations, 43, 228–237.

Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S.

(1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in

the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Leiblum, S., & Breszssnyak, M. (2006). Sexual chemistry: Theo-

retical elaboration and clinical implications. Sexual and Rela-

tionship Therapy, 21, 55–69.

McDonald, R. P., & Ho, M. H. R. (2002). Principles and practice

in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods,

7, 64–82.

Metts, S. (2004). First sexual involvement in romantic relation-

ships: An empirical investigation of communicative framing,

romantic beliefs, and attachment orientation in the passion turn-

ing point. In J. H. Harvey, A. Wenzel, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), The

handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 135–158). Hill-

sdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Peplau, L. A., Rubin, Z., & Hill, C. T. (1977). Sexual intimacy in

the dating relationship. Journal of Social Issues, 33, 86–109.

Regnerus, M. D. (2007). Forbidden fruit: Sex and religion in the

lives of American teenagers. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Reiss, I. L. (1960). Premarital sexual standards in America. New

York: Free Press.

Reiss, I. L. (1967). The social context of premarital sexual per-

missiveness. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Sassler, S., & Kamp Dush, C. M. (2009, March). The pace of

relationship progression: Does timing to sexual involvement

matter? Paper presented at a National Center for Family and

Marriage Research Conference, Bowling Green State University.

Sprecher, S., & McKinney, K. (1991). Attitudes about sexuality in

close relationships. In K. McKinney, & S. Sprecher, (Eds.),

Sexuality in close relationships. (pp. 1–23) Hillsdale, NJ: Law-

rence Erlbaum.

Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. (1992). Assessing commitment

in personal relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 54,

595–608.

Stanley, S. M., Rhoades, G. K., & Markman, H. J. (2006). Sliding

vs. deciding: Inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect. Fam-

ily Relations, 55, 499–509.

Teachman, J. (2003). Premarital sex, premarital cohabitation, and

the risk of subsequent martial dissolution among women. Journal

of Marriage and the Family, 65, 444–455.

U.S. Religious Landscape Survey. (2007). PEW forum on religious

and public life. http://religions.pewforum.org/reports

Received March 15, 2010

Revision received August 24, 2010

Accepted August 26, 2010

䡲

774 BUSBY, CARROLL, AND WILLOUGHBY

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.