DEMOGRAPHIC RESEARCH

VOLUME 31, ARTICLE 36, PAGES 1107–1136

PUBLISHED 12 NOVEMBER 2014

http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol31/36/

DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2014.31.36

Research Article

Free to stay, free to leave: Insights from Poland

into the meaning of cohabitation

Monika Mynarska

Anna Baranowska-Rataj

Anna Matysiak

This publication is part of the Special Collection on “Focus on Partnerships:

Discourses on cohabitation and marriage throughout Europe and Australia,”

organized by Guest Editors Brienna Perelli-Harris and Laura Bernardi.

© 2014 Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak.

This open-access work is published under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution NonCommercial License 2.0 Germany, which permits use,

reproduction & distribution in any medium for non-commercial purposes,

provided the original author(s) and source are given credit.

See http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/de/

Table of Contents

1

Introduction

1108

2

Literature overview: Freedom in cohabitation

1109

3

The Polish context

1112

4

Data and methods

1115

5

Results

1117

5.1

How is freedom in cohabitation understood?

1117

5.2

Testing and binding – How and why is freedom attractive?

1120

5.3

“Trying harder” in a relationship – Freedom and the relationship

between the partners

1122

6

Summary and discussion

1124

7

Acknowledgements

1128

References

1129

Demographic Research: Volume 31, Article 36

Research Article

http://www.demographic-research.org 1107

Free to stay, free to leave:

Insights from Poland into the meaning of cohabitation

Monika Mynarska

1

Anna Baranowska-Rataj

2

Anna Matysiak

3

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Previous studies have shown that in Poland cohabitation is most of all a transitory step

or a testing period before marriage. Polish law does not recognize this living

arrangement and it has been portrayed as uncommitted and short-lived. However, few

studies have investigated what cohabitation means for relationships, especially with

respect to freedom.

OBJECTIVE

We explore how young people in Poland understand and evaluate freedom in

cohabitation. We investigate how they view the role freedom plays in couple dynamics

and in relationship development.

METHODS

We analyze data from focus group interviews conducted in Warsaw with men and

women aged 25–40. We identify passages in which opinions on cohabitation and

marriage are discussed, and use bottom-up coding and the constant comparative method

to reconstruct different perspectives on the issue of freedom in cohabitation.

RESULTS

The respondents argued that cohabitation offers the partners freedom to leave a union at

any time with few repercussions. On the negative side, the freedom related to

cohabitation brings insecurity, especially for young mothers. On the positive side, it

offers relaxed conditions for testing a relationship, grants partners independence, and

1

Institute of Psychology, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw, Poland.

E-Mail: m.my[email protected]du.pl.

2

Institute of Statistics and Demography, Warsaw School of Economics, Poland. Department of Sociology,

Umeå University, Sweden.

3

Wittgenstein Centre (IIASA, VID/OEAW, WU), Vienna Institute of Demography / Austrian Academy of

Sciences, Austria. Institute of Statistics and Demography, Warsaw School of Economics, Poland.

Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak: Freedom in cohabitation in Poland

1108 http://www.demographic-research.org

encourages cohabitors to keep their relationship interesting, precisely because it is

fragile and easy to dissolve.

CONCLUSIONS

The open nature of cohabitation offers benefits to partners, but does not provide secure

conditions for childbearing. As long as the couple is not planning to have children,

however, the benefits of cohabitation are likely to be seen as outweighing the

disadvantages.

1. Introduction

In many developed countries marriage has lost ground to cohabitation, and living

together before marriage has become a standard element in the process of relationship

formation (Heuveline and Timberlake 2004; Sobotka and Toulemon 2008). Young

couples are spending more and more time cohabiting, and a growing number of children

are born and raised in informal unions (Perelli-Harris et al. 2012; Perelli-Harris et al.

2010). It is therefore not surprising that researchers are increasingly interested in

understanding how informal cohabitation differs from marriage, and why some

individuals choose this living arrangement instead of marriage.

Researchers frequently notice that the diffusion of cohabitation is associated with

the liberalization of social norms and increasing freedom of choice (Ramsøy 1994;

Thornton and Philipov 2009; Lesthaeghe 2010), and that unregistered cohabitation

might be an attractive option because it gives partners a greater degree of independence

and personal freedom in relationships. It is thus assumed that this living arrangement

allows for the pursuit of individual goals and self-realization (Surkyn and Lesthaeghe

2004). But while it allows partners to sustain their economic as well as their personal

independence to a greater extent than they could in marriage (Poortman and Mills 2012;

Surkyn and Lesthaeghe 2004), it might also be associated with a lower commitment or

even a lower sense of moral obligation between partners (Adams and Jones 1997).

Cohabitation might also be perceived as attractive because it provides the couple with

an opportunity to test out the relationship without having to enter into long-term

commitment (Heuveline and Timberlake 2004; Murrow and Shi 2010; Perelli-Harris et

al. 2014). But the lack of legal bonds is associated with a degree of insecurity, which

may have a negative impact on the quality of the relationship (Rhoades, Stanley, and

Markman 2009), and which could influence the partners‟ choices regarding the

development of the relationship (e.g., childbearing decisions). All in all, the freedom

that is experienced by the partners in an informal union is, in our view, a complex

concept, and its meaning depends on a country-specific cultural and institutional

Demographic Research: Volume 31, Article 36

http://www.demographic-research.org 1109

context. Therefore we believe that in order to explain the status of cohabitation and the

process of the diffusion of this living arrangement in a given society, we must first

understand how that society perceives freedom in the context of couple relationships.

In this paper we explore the concept of freedom offered by cohabitation in the

Polish context. Young Poles are engaging in pre-marital cohabitation with increasing

frequency, although still less frequently than their counterparts in Western or Northern

Europe (Sobotka and Toulemon 2008). Cohabitation is not legally recognized in

Poland, and the country‟s traditions and social norms strongly support marriage

(Mynarska and Bernardi 2007; Mynarska and Matysiak 2010; Soons and Kalmijn

2009). Understanding how young Poles perceive freedom in cohabitation helps us to

better understand which factors tend to encourage young people to enter or discourage

them from entering into this living arrangement, and which therefore shape the process

of cohabitation diffusion in Poland.

In this study we analyze data from focus group interviews with 69 men and women

aged 25–40, conducted in Warsaw in 2012. The free nature of cohabitation (related

mostly, but not exclusively, to easy union dissolution) was central in the narratives of

the interviewees, providing us with rich material on the analyzed topics. Before

presenting our study we will provide an overview of how various aspects and

consequences of the more open nature of informal unions have been presented in the

literature. We will also briefly describe our research context, providing key information

on cohabitation in Poland.

2. Literature overview: Freedom in cohabitation

Even though cohabitation has become increasingly widespread, in most countries it still

differs from marriage in terms of social and legal recognition. Moreover, the meanings

attached to cohabitation and the motives for entering into an informal union are

different from those related to marriage (Heuveline and Timberlake 2004). These

discrepancies might be less pronounced in countries where cohabitation is very

common and where legal regulations mitigate the differences between the two living

arrangements, but in most countries cohabitation remains distinguishable from

marriage. Consequently, as we will present it in the following paragraphs, researchers

often discuss the uncommitted and open nature of this living arrangement and the

various consequences it might have for partners.

First, by entering into a non-marital and informal living arrangement, a couple may

benefit from companionship, closeness, and sexual intimacy with a partner without

having to make any long-term commitment (Rindfuss and Van den Heuvel 1990;

Casper and Bianchi 2002). As partners continue dating and enjoying each other‟s

Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak: Freedom in cohabitation in Poland

1110 http://www.demographic-research.org

company, cohabitation offers them the opportunity to spend more time together, and

thus may be seen as a natural stage in the development of the relationship (Manning and

Smock 2005; Mynarska and Bernardi 2007). Some studies emphasize the practical

benefits of sharing a household with a partner, including convenience, the ability to

share housing arrangements, and the potential to save money (Sassler 2004; Lindsay

2000). „Co-residential dating‟ provides partners with all of the benefits of sharing a

household, emotional, physical, and practical. At the same time the partners can avoid

having to enter into long-term obligations, and can maintain their personal freedom.

An important aspect of informal unions that has been mentioned in the literature is

that the partners are given the opportunity to test their relationship (Mynarska and

Bernardi 2007; Murrow and Shi 2010; Perelli-Harris et al. 2014). Living together

allows partners to learn more about each other and assess their compatibility. Young

people are increasingly willing to move in together before marriage, as they are free to

leave if the trial period ends in failure. This process can lessen the danger of having an

unhappy marriage that eventually ends in divorce. Thus, young people view pre-marital

cohabitation as a means of improving their chances in future marriage, and of “divorce-

proofing” their relationship (Manning and Cohen 2012; Kline et al. 2004; Thornton and

Young-DeMarco 2001). Cohabitation is therefore frequently conceptualized as a “trial

marriage” or a “testing period” before marriage (Heuveline and Timberlake 2004;

Seltzer 2000; Kiernan 2004).

Moreover, the free nature of cohabitation might appear attractive to individuals

with more egalitarian or liberal attitudes. First, several studies have shown that as

cohabiting partners tend to have more independence and personal freedom than married

couples, they often experience a greater degree of equality in the partnership; for

instance, they experience greater financial autonomy as well as a more equal division of

household labor (Brines and Joyner 1999; Baxter 2005; Baxter, Haynes, and Hewitt

2010; Davis, Greenstein, and Gerteisen 2007; Heimdal and Houseknecht 2003; Hiekel,

Liefbroer, and Poortman 2014). This arrangement may therefore be especially attractive

to individuals who do not want to adhere to traditional gender roles. Second, it might be

appealing to those who do not believe in the institution of marriage or who want to

express their rejection of the authority identified with the Catholic Church (Clarkberg,

Stolzenberg, and Waite 1995; Corijn and Manting 2000; Villeneuve-Gokalp 1991).

However, the open nature of cohabitation may discourage partners who seek the

security provided by institutionalized partnerships that are regulated by law. Steven

Nock described cohabitation as an “incomplete institution” that is “not yet governed by

strong consensual norms or formal laws” (Nock 1995, p. 74). In recent years many

western countries have introduced laws and policies that recognize cohabitation, or

even place it on an equal footing with marriage in some respects or under certain

conditions (Bowman 2004; Bradley 2001; Perelli-Harris and Gassen 2012).

Demographic Research: Volume 31, Article 36

http://www.demographic-research.org 1111

Nevertheless, non-marital cohabitation generally retains its informal character, and even

in countries with registered partnerships the couples in these unions are less financially

interdependent than married couples (Poortman and Mills 2012). Consequently,

unmarried partners are frequently worse off with respect to property rights, taxation,

survivor‟s pension, inheritance rights, and adoption rights (Perelli-Harris and Gassen

2012). This lack of institutional security is one of the reasons why cohabitation is

generally not perceived as being an appropriate setting for childrearing, and why in

most developed countries cohabiting couples who want to become parents sooner or

later sacrifice the freedom associated with cohabitation and decide to get married

(Perelli-Harris et al. 2012).

Moreover, cohabitation has often been described as an “incomplete institution”

because in many countries it still lacks the social status of a married union. In some

countries there are no commonly used terms to describe a cohabiting partner (Manning

and Smock 2005; Mynarska and Bernardi 2007) and there is no term for the non-marital

equivalent of an in-law (Nock 1995). Although cohabitation has become increasingly

accepted throughout the developed world (Thornton and Young-DeMarco 2001;

Mynarska and Bernardi 2007) there are still marked differences between countries in

terms of attitudes toward informal unions (Soons and Kalmijn 2009). Especially in

Catholic countries, such as Poland, where there is a lesser degree of social acceptance

of informal unions, cohabitors might continue to experience certain forms of

stigmatization. Cohabitation may thus imply not only the partners‟ independence but

also some level of social detachment (Shapiro and Keyes 2008).

Finally, the fact that it is easier to dissolve an informal union than marriage offers

freedom but at the same time implies a lack of stability and certainty. Researchers have

noted that marriage signals a long-term commitment not only to the partners themselves

but also to the wider community (Cherlin 2000, 2009; Mynarska and Bernardi 2007).

There is no equivalent declaration in cohabitation, even in countries where it is possible

to register a partnership. Informal unions are thus associated with less binding legal and

interpersonal commitment (Poortman and Mills 2012). The absence of marital vows

might also be associated with a reduced sense of moral obligation (Adams and Jones

1997).

The open nature of cohabitation may also have different effects on the behavior of

the partners. Having the freedom to dissolve the union offers the partners the

opportunity to prove the quality of their match, but it can be viewed as a source of

uncertainty regarding the future prospects of the union. The first possible consequence

of this uncertainty is that the partners may avoid making joint investments in couple-

specific goods and resources (Brines and Joyner 1999; Drewianka 2006). For example,

cohabiting partners may have a lower propensity to have children together and to

develop relationships with the other partner‟s relatives (Hogerbrugge and Dykstra

Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak: Freedom in cohabitation in Poland

1112 http://www.demographic-research.org

2009). Couples in informal unions may avoid pooling resources, holding jointly owned

property, and adopting a division of responsibilities within and outside of the household

in which one of the partners is economically dependent on the other (Lyngstad, Noack,

and Tufte 2011). Being in an informal union may also encourage the partners to

develop their own skills and interests, rather than sacrificing them for the sake of the

joint household. This may have implications for the partners‟ behavior during conflicts.

Partners who are more concerned with their own independence and their own (rather

than joint) interests may be less consensus-seeking and less willing to give up some of

their own preferences for the sake of resolving problems in their relationship (Cohan

and Kleinbaum 2002).

However, the uncertainty about the future of the partnership may also have a

seemingly contradictory effect, in that it may encourage the partners to put considerable

effort into keeping the union attractive for both parties. Because the partners do not take

the stability of the union for granted, they may work hard on a daily basis to make the

relationship last. Thus, compared to married couples, cohabiting couples may invest

more time, energy, and financial resources in the partnership (Drewianka 2004;

Grossbard-Shechtman 1982; Grossbard-Shechtman 1993), and display emotional and

physical affection and intimacy more frequently (Hsueh, Morrison, and Doss 2009).

All in all, the freedom and independence offered by cohabitation and the informal,

deinstitutionalized character of this type of union can be beneficial to the partners, but –

as the literature overview shows – it also holds various risks for a couple. The open

nature of cohabitation may have mixed effects on the behavior and interactions of the

partners toward each other, as well as toward the partners‟ relatives. The freedom that

cohabitation offers is likely to be a particularly relevant factor in young people‟s

choices and actions in countries where cohabiting and married couples have totally

different legal and social statuses. In this paper we investigate such a country, and

explore how the open nature of cohabitation is perceived in Poland.

3. The Polish context

Even though Poland is not „immune‟ to the spread of cohabitation (Matysiak 2009), this

living arrangement is still much less common in Poland than in other European

countries (Sobotka and Toulemon 2008; Hoem et al. 2010; Kasearu and Kutsar 2011).

According to cross-sectional data, non-marital unions make up just 3% to 6% of all

unions in Poland (depending on the data source, Kasearu and Kutsar 2011; Soons and

Kalmijn 2009; Matysiak and Mynarska 2014). Nevertheless, growing numbers of

Polish people are cohabiting for at least a short period of time. The newest estimates

based on retrospective data from the Generations and Gender Survey have indicated

Demographic Research: Volume 31, Article 36

http://www.demographic-research.org 1113

that the proportion of entries into unions that took the form of cohabiting arrangements

increased from 26% in the early 1990s to 60.5% in the second half of the 2000s

(Matysiak and Mynarska 2014). These cohabiting unions are, however, quite short, and

are often transformed into marriages. Moreover, in the qualitative narrations of young

Poles, cohabitation has been portrayed as a transitory step or a testing period before

marriage (Mynarska and Bernardi 2007).

Marriage still represents the highest stage in the development of a relationship.

The majority of Poles want to get married and strongly value marriage (Pongracz and

Spéder 2008), viewing it as a signifier that a relationship has passed the test and has

proved good enough to be converted into a permanent commitment (Mynarska and

Bernardi 2007). Moreover, most Poles believe that marriage, not cohabitation, is the

proper context for childbearing (Mynarska and Bernardi 2007; Mynarska and Matysiak

2010). Even though the share of extra-marital births has increased in Poland, the

majority of women who become pregnant while in an informal union decide to marry

before or soon after the child is born. In the years 2006–2010 conceptions in

cohabitation accounted for 23% of all conceptions in unions, but only 9% of children

were born and raised by cohabiting parents up to the age of two (Matysiak and

Mynarska 2014). Individuals who remain in an informal union for a longer period of

time or who have a child in cohabitation usually have some legal, material, or personal

constraints that prevent them from marrying (Matysiak and Mynarska 2014; Kasearu

and Kutsar 2011).

Cohabitation in Poland is not only rare and temporary: it is also not recognized

under Polish law (Matysiak and Wrona 2010; Stępień-Sporek and Ryznar 2010).

Cohabiting partners have neither special rights nor obligations that stem from living

together. Unlike married couples, cohabiting couples cannot benefit from the option to

file their income taxes jointly or to co-insure the non-working partner, nor do they have

the right to claim financial support from their partner if they lose their job or face

financial problems. Cohabiting fathers do not automatically acquire fatherhood status,

as it is the case in marriage, but instead have to declare their fatherhood in court and

obtain the mother‟s consent. No rights are granted to cohabiting partners in the case of

death or union disruption. Consequently, a cohabiting partner cannot inherit property

from his or her deceased partner or collect survivor pensions or alimonies. Furthermore,

there are no special rules that regulate the division of property and goods after

separation. Thus, cohabiting couples who want to separate have to refer to general

property law, which puts the less affluent partner in an inferior position. The lack of

legal recognition of cohabitation in Polish law implies that cohabiting partners can

separate without any legal consequences or any need to undergo official procedures.

Marital partners, by contrast, have to obtain the consent of the partner if they want to

exit the union and get a divorce. In 2012 the median duration of divorce proceedings

Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak: Freedom in cohabitation in Poland

1114 http://www.demographic-research.org

was around four months, but for around 12% of couples it took more than a year to

obtain a legal divorce (Styrc 2010; CSO 2013).

In the absence of regulations that define the rights and obligations of partners

living in non-marital unions, cohabiting partners may try to clarify their arrangement by

signing a private contract. The contract can regulate personal relations between

partners, such as the power of attorney or the distribution of property after the

breakdown of the union, but only if the rights of third parties are not affected (Stępień-

Sporek and Ryznar 2010). Thus in practice such a contract has very limited powers

when regulating issues such as inheritance (Matysiak and Wrona 2010). Furthermore, it

cannot give cohabitors rights that are legally guaranteed only to spouses, such as

alimony or joint taxation rights.

Cohabitation in Poland is less socially acceptable than it is in many other European

countries. International surveys such as the Population Policy Acceptance Study

(Pongracz and Spéder 2008), the International Social Survey (Liefbroer and Fokkema

2008), and the European Social Survey (Aassve, Sironi, and Bassi 2013) have

consistently found that Polish respondents were less likely to agree with statements

such as “it is acceptable for a couple to live together without intending to get married”

than respondents in other developed countries. In in-depth interviews, Polish

respondents observed that their families do not recognize cohabiting partners as a „real

couple‟ and that in the Polish language there are no positive expressions to describe a

cohabiting union (Mynarska and Bernardi 2007).

In sum, even if cohabitation is becoming more frequent in Poland, it is still

subordinate to marriage, and clearly remains an „incomplete institution‟. Consequently,

Poland provides a very interesting context for analyzing how the non-institutionalized

and free character of informal cohabitation is perceived, and what role this concept

plays in the process of union formation. The freedom that cohabitation offers has not

yet been investigated in Poland. Explorations of the perception of freedom have also

been relatively rare in the existing studies on cohabitation, as they have tended to

concentrate on the concept of commitment instead. In our view, shifting the focus from

commitment to freedom provides us with new perspectives on why individuals choose

to enter informal unions. Consequently, this approach may provide us with new

explanations of the position and the role of cohabitation in Polish society. In our study

the following research questions are posed: How do young Poles understand and

evaluate freedom in cohabitation? What meaning does this concept have? How are the

negative and the positive aspects of freedom defined in the Polish context? And, finally,

how do young Poles view the role freedom plays in couple dynamics and relationship

development?

Demographic Research: Volume 31, Article 36

http://www.demographic-research.org 1115

4. Data and methods

In this study we use narrative material from eight focus group (FG) interviews which

were carried out in Poland (Warsaw) in March 2012. The data were collected following

research design developed by the Focus on Partnership team. The team members

collaborated to create a standardized focus group guideline, which was used to direct

the focus group discussions. The sample selection criteria were uniform across the

countries. For further information on this project, please see Perelli-Harris et al. (2014)

or www.nonmarital.org.

The FGs in Poland were organized with support from a research agency, ARC

Rynek i Opinia. The agency started recruitment using their own contact database,

contacting individuals who had participated in the past in market research or social

studies conducted by the agency, who were between the ages of 25 and 40, and who

lived in or near Warsaw. The individuals were asked to participate in the study or to

refer the recruiter to another person in the given age range (a snowball method).

Individuals who had participated in qualitative market research in the previous 12

months or more than twice in the past were excluded from the sample. Only people of

Polish origin were included in the study.

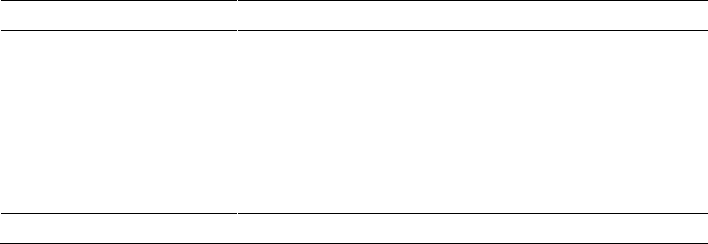

The sample was stratified by gender and education to allow us to compare the

views of men and women and of individuals with higher and lower levels of educational

attainment. Individuals with only primary, vocational, lower-secondary, upper-

secondary (general or professional), or post-secondary (non-tertiary) education were

assigned to the lower level, while individuals with tertiary (BA/MA) or post-tertiary

education were assigned to the higher level. Four FGs were organized for each

education level, two with male respondents and two with female respondents. In total

69 respondents for eight focus groups were recruited. Each group included eight or nine

participants with various union statuses, some of whom had children and some of

whom were childless. Each respondent received approximately 20 EUR for

participation. The basic characteristics of the respondents in each group are presented in

the table below.

Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak: Freedom in cohabitation in Poland

1116 http://www.demographic-research.org

Table 1: Sample characteristics

FG1

FG2

FG3

FG4

FG5

FG6

FG7

FG8

total

Gender

Men

Women

8

–

–

9

9

–

–

9

9

–

8

–

–

9

–

8

34

35

Education

Medium/low

High

8

–

9

–

9

–

9

–

–

9

–

8

–

9

–

8

35

34

Marital

status

Single/divorced

Married

4

4

4

5

2

7

6

3

5

4

4

4

6

3

4

4

35

34

Parity

Childless

Parent

4

4

4

5

4

5

7

2

5

4

5

3

6

3

3

5

38

31

Total N of participants

8

9

9

9

9

8

9

8

69

The mean ages of the men and women in the sample were exactly the same: 32.2.

Even though marital status and parity were not among the recruitment criteria, we were

able to include respondents with different family situations in the sample: About half of

the respondents were married at the time of the study, and of the unmarried individuals

thirteen were in a relationship (eight were cohabiting and five were „living apart

together‟). Slightly more than half of the participants were childless. Only four of the

married respondents were childless, and among the unmarried participants only one was

a single parent. While we do not have detailed information on the respondents‟

partnership histories, during the discussion several of the married respondents revealed

that they had cohabited in the past. Since the focus groups were conducted in order to

help us better understand general social views on informal unions among young Poles,

it was of benefit to the study that the sample included both respondents who had and

had not cohabited in the past.

The FGs were conducted at the premises of the research agency by a Polish-

speaking researcher who was involved in the Focus on Partnership project. The

standardized focus group guideline covered topics such as the disadvantages and

advantages of living together without being married, the motivations for and the

barriers to getting married, and the policies and laws related to cohabitation and

marriage (see: Perelli-Harris et al. 2014). Each FG was recorded and transcribed

verbatim. The text was coded in NVivo using a combination of top-down and bottom-

up coding. In the first step the moderator coded the material according to the guideline

questions (coding by questions). Next, open coding was performed and a table was

prepared that summarized all of the issues mentioned in response to each question and

in each group. For instance, a table on the disadvantages of cohabitation included all of

the arguments brought up by the participants in response to the question on this issue.

For each point that was mentioned the most representative quotes were also included.

Demographic Research: Volume 31, Article 36

http://www.demographic-research.org 1117

A comparison of these tables allowed us to identify recurring themes and to

explore the relationship between them (constant comparative method, Glaser and

Strauss 1967; Glaser 1965). Two themes were dominant in the respondents‟ remarks,

recurring in reaction to different questions and discussed in various contexts: (1) the

role of the Catholic religion/traditions in the union formation process; and (2) the

perception that a cohabiting union is easy to terminate (“one is free to leave at any

time”). This paper draws on the material related to the latter theme.

It should be noted that while the respondents discussed the open nature of

cohabitation, they frequently contrasted it with the committed nature of marriage. While

our focus in this paper is on cohabitation, some references to marriage will of course be

necessary.

5. Results

5.1 How is freedom in cohabitation understood?

It was apparent from the FGs that the respondents view freedom in cohabitation

primarily as the ability to leave the relationship easily whenever they want to.

According to the participants, if a couple lives together without being married “it‟s

easier to walk away”, a partner can “pack a suitcase” and go, and the partners have “an

easy way out”. The respondents focused on three aspects of cohabitation in particular:

the lack of legal formalities at separation, the reduced sense of moral obligation, and the

partners‟ greater degree of independence.

First and foremost, the respondents agreed that cohabitation is easy to terminate

because the dissolution does not involve any formalities; i.e., the partners are legally

free to leave at any time and can do so without difficulty. Marital dissolution was

perceived very differently. The respondents agreed that divorce is associated with more

stress and hassle, and in all of the FGs there was some discussion about the problems

related to divorce. The participants argued that if you wish to terminate a marriage “you

have to go to a court, and you have to prove your grounds for divorce”; “you have to

file for a divorce, wait, pay loads of money”; “there are tons of official papers”; and

you have to be willing to discuss “very personal things in public”. Several respondents

provided real-life examples of long and painful divorces, emphasizing that a couple that

decides to get divorced has “a long and difficult path ahead”.

Meanwhile, most of the respondents indicated that they believe cohabitation offers

an effortless way out of a union:

Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak: Freedom in cohabitation in Poland

1118 http://www.demographic-research.org

There are no formalities, no divorce, no lawsuit, no lawyers, no washing your

dirty linen in public. (FG3, man, low/medium educated)

Without unnecessary formalities (…) less fighting, and no need to wait for a

court hearing for more than a year. (FG4, woman, low/medium educated)

Similar statements were made in all of the groups, and the vast majority of the

respondents shared these views. Only one respondent (a highly educated woman) tried

to argue that it is not easy to leave a cohabiting union that has existed for a long period

of time, especially when the couple have joint children. Other participants

acknowledged that it is more difficult to separate when children are involved, but

nonetheless argued that separation is still much easier in cohabitation. Importantly, with

the aforementioned exception, the respondents did not spontaneously bring up the topic

of separation in an informal union where children were involved. When they spoke of

leaving a non-marital partner they did not mention children, and it was clear that a

cohabiting union is perceived as being childless. Thus, according to most of the

respondents, leaving an informal union is easy. In one group, a female respondent put it

quite bluntly:

Unless they have a mortgage together, but otherwise he packs his stuff and

leaves. There is no divorce, no need to divide things… It‟s like they have

never been together. (FG7, women, highly educated)

A few other issues also arose when the respondents discussed freedom in

cohabitation. The interviewees spoke of basic issues such as the fidelity and loyalty of

the partners, but also of the division of household tasks and the ability to spend money

freely. These topics were not dominant in the narratives, but they were discussed in

detail in two focus groups with women (one with a lower and one with a higher level of

education). They also appeared to be of varying degrees of personal importance to the

respondents. We describe them briefly below, to show the complexity of the concept of

freedom.

First, the women argued that marriage offers some protection against cheating,

some moral obligation that is absent in cohabitation. According to our female

respondents, a man with a wedding ring on his finger feels “morally, internally”

obliged. The women complained that cohabiting men may claim that they are single

(“free”), and may even seek out sexual encounters. Examples of work-related trips

were given, as in the following quote:

Demographic Research: Volume 31, Article 36

http://www.demographic-research.org 1119

You are right, it is necessary to put a wedding ring on a man‟s hand,

because… well… They are aware that they are not free [=single] then.

Otherwise, he goes on a team-building trip at work and he says he is free.

(FG8, woman, highly educated)

Although women mainly discussed the issue of infidelity in relation to men‟s

behavior, one respondent spoke in more general terms, applying it to both sexes:

There are people who live together, and they don‟t have this wedding ring yet,

so they think they can be unfaithful because he/she is not married yet. (FG2,

woman, low/medium educated)

Second, some female respondents perceived cohabitation as being a more open

relationship because a cohabiting woman can maintain her independence in everyday

life. For instance, a woman in an informal union does not need to consult her partner

before going out or spending money. As one respondent put it:

I‟m independent. I buy my own clothes, my shoes, my bags with my own

money. (FG8, woman, highly educated)

Another respondent remarked that, unlike a wife, a woman in an informal union is

not obliged to cook or clean:

It‟s what a husband expects, a wife must clean and cook. And I‟m not like

that, I am not going to cook dinners and all this stuff. (FG2, woman,

low/medium educated)

Apparently, cohabitation may be seen as offering women a more free and

emancipated lifestyle.

The lack of legal obligations, the reduced sense of moral obligation, and women‟s

independence were the three key aspects of freedom discussed by the respondents. Was

the free nature of cohabitation generally perceived as being attractive? Or did the

participants see more risks than benefits? We answer these questions in the following

section.

Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak: Freedom in cohabitation in Poland

1120 http://www.demographic-research.org

5.2 Testing and binding – How and why is freedom attractive?

Informants generally perceived the open nature of cohabitation and the ease with which

these unions can be terminated as attractive, especially in the context of relationship

testing. Cohabitation was mainly seen as a trial period during which partners get to

know each other better and find out whether they can live together successfully. As

couples do not consider having children at this stage, cohabitation offers couples a risk-

free opportunity to test their relationship.

The testing role of cohabitation was cited by the respondents as being a key benefit

of this living arrangement, and one of the central reasons why consensual unions are

becoming increasingly common in Poland. In their view, pre-marital cohabitation is a

stage in which the partners are attempting to enter into a more serious relationship, as

they move from “seeing each other twice a week” to “solving problems together”. But

at the same time they still have the opportunity to leave the relationship without any

damaging consequences. Statements like the following were made in all of the groups:

People want to get to know each other better and to grow into a decision to

marry, and maybe they want to have an option for an easy way out of this

relationship. (FG2, woman, low/medium educated)

Living together before a wedding creates this opportunity to get to know each

other better. And it gives time to think about it and to make the right

decision… (FG6, man, highly educated)

While marriage might be viewed as a sign that the trial has succeeded, breaking up

is a natural, expected, and accepted consequence if it fails. In this sense, cohabitation

allows the partners to make a wise, informed choice for their future, and allows them

“to eliminate mistakes”.

As participants strongly emphasized the testing character of pre-marital

cohabitation, they generally evaluated cohabitation favorably as allowing for an easy

way out. But the participants also stressed that such a testing period should not last too

long, and that the freedom related to cohabitation may become disadvantageous as the

union persists and the couple grows older, accumulates possessions, and has children.

At some point in the discussion the moderator explicitly asked the respondents about

the rights of married and unmarried partners at separation. The respondents noted that a

cohabiting woman would suffer more than a married woman in the event of a separation

if there had been a “traditional” division of household tasks, and if the woman and her

children depended financially on the male partner. If the informal union was terminated,

such a woman would be left on her own and “she has nothing at this moment”. By

contrast, “marriage gives you something, you are entitled to half of all possessions”

Demographic Research: Volume 31, Article 36

http://www.demographic-research.org 1121

and also to maintenance payments from the ex-husband

4

. The following quote is

representative of how the respondents spoke about this issue:

There is greater financial security in the case of marriage. At least people

believe so. That if there is has been a wedding, there is the support. (FG6,

man, highly educated)

This gendered perspective is also reflected in the fact that the women in our

sample said they perceive cohabitation as being more convenient for men. The ability to

leave at any time and the lack of moral obligation to a partner is seen as attractive for

men. The women argued that:

It is easier particularly for men in such relationships, because they can

always walk away. (FG2, woman, low/medium educated)

In the interviews we found passages illustrating that women in particular believe it

is extremely easy for a man to leave an informal union even if a child is involved. The

following quote comes from the discussion with highly educated women:

He doesn‟t even need to pay really, he can just say: Bye! And you can just go

on looking for him. He doesn‟t have to… during a divorce there is a court to

decide – for instance – with whom a child stays. And [in cohabitation] there is

no such thing. He just walks away. He can say „Bye‟ and he doesn‟t even need

to see a child at all. Nothing. (FG7, woman, highly educated)

Even though some of the women argued that this depends on the individuals

involved, and that even in cohabitation the partners can make fair arrangements upon

separation, the dominant discourse indicated that the women believe that consensual

unions are more insecure for women with children. Notably, in two of the groups (men

with lower levels of education and women with higher levels of education) some of the

respondents asserted that when children are involved marriage is also beneficial to the

man, because a cohabiting father might face considerable difficulties in gaining the

right to see his child after the partners separate. This point was made even though

Polish law does not make any distinction in parental rights based on the parents‟ marital

status.

4

In theory, maintenance payments can be paid by women as well as by men. Nonetheless, in Poland they are

usually paid to women, and in the FGs this aspect was discussed only in relation to women‟s material

security.

Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak: Freedom in cohabitation in Poland

1122 http://www.demographic-research.org

In general, while both the men and the women agreed that pregnancy should not be

a reason to get married – and that they do not favor so-called “shotgun weddings” –

they also agreed that marriage is the proper context for childbearing. It goes beyond the

scope of this paper to present this topic in detail, but it should be emphasized that the

respondents universally agreed that if the partners love each other and are planning a

future together, they should get married before having a child. The decisions to have a

child and to get married are intertwined, according to the interviewees.

To sum up, the open nature of cohabitation is evaluated differently at different

stages of a relationship‟s development. It is considered attractive and beneficial while

the relationship is being tested. But with time the partners are expected to want the

increased levels of commitment and of mutual responsibility that only come from

marriage. In particular, marriage is deemed important for women in the context of

childbearing.

5.3 “Trying harder” in a relationship – Freedom and the relationship between the

partners

In the last section we will describe the respondents‟ views on how the freedom offered

by cohabitation influences couple dynamics and the interactions between partners.

Again, both the negative and the positive consequences of freedom were discussed.

First, the respondents agreed that during the trial period it is expected and accepted

that a cohabiting couple will separate if their relationship does not work out, and that

the partners may choose to separate quickly rather than to attempt to resolve their

problems and differences. According to the respondents, cohabitation offers the partners

a risk-free opportunity to test their relationship, but they warned that this arrangement

may discourage partners from making an effort to “save” their relationship. Thus, the

respondents appear to believe that cohabiting partners may be more likely than married

couples to separate if they experience minor problems that could have otherwise been

resolved. In one group, the women discussed this issue in the following way:

– It is easier to make this decision about breaking up [in cohabitation], otherwise

a person might still try to fight for it;

– Sometimes you just get upset and simply walk out;

– You don‟t think it through. A small issue and that‟s it…;

– These are reasons that can make you break up, but maybe or most likely you

would not divorce because of them. (FG7, women, highly educated)

Demographic Research: Volume 31, Article 36

http://www.demographic-research.org 1123

The contrast to marriage is apparent here. The respondents generally observed that

married partners are less likely than cohabiting partners to give up easily when conflicts

or problems arise. According to the interviewees, married couples “try harder” to

resolve the conflict and to prevent union dissolution. The following quotes are

representative of our respondents‟ opinions:

There is less responsibility for the relationship [in cohabitation] somehow. As

we said before, it is easier to walk away. If something is falling apart, one

puts in less effort. I think that in marriage, one tries harder. (FG8, woman,

highly educated)

If people are more conservative, being married might encourage them to put

in more effort if a crisis arises. (FG5, man, highly educated)

The respondents further noted that efforts to save the relationship might be more

important when children are involved. Once again, a link between marriage and

childbearing was revealed.

But the open nature of cohabitation could have another effect. The respondents

noted that, because an informal union is less secure and is easy to dissolve, the partners

need to make ongoing efforts to keep the relationship attractive, and to avoid the

problems that might lead to separation. These issues were discussed in four of the

groups (women with high and low levels of education, men with high levels of

education).

I think that people maybe are trying harder [in cohabitation], because it‟s not

like I don‟t have to make any effort anymore because he is my husband

already, he is and he will be. You always have to care about the other person.

But I think that sometimes people think that it‟s my wife or husband so I can

put on 20 kg now. (FG7, woman, highly educated)

People let go of more things [in marriage] and it affects a relationship very

badly. People rest on their laurels, stop caring, once they are married. And

otherwise, they are not so sure of themselves. (FG5, man, highly educated)

Interestingly, the phrase “trying harder” reappears in a new context. Previously

the respondents had said that married couples “try harder” to resolve their problems in

order to avoid divorce. Here, a cohabiting couple “tries harder” not to resolve conflict,

but to avoid it. The “trying harder” in cohabitation is implemented before the conflicts

arise, and is meant to ensure that the partners remain attractive to each other. The

Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak: Freedom in cohabitation in Poland

1124 http://www.demographic-research.org

respondents mentioned superficial behaviors that might change if the partners start

feeling too secure: e.g., the partners might stop watching their weight and start dressing

“sloppily”, the woman might stop wearing make-up, and the man might start drinking

beer in front of the TV. But the respondents also spoke in more general terms of

“working harder” or being “more dedicated” in cohabitation. According to the

participants, if a cohabiting partner does not “try harder”, the other partner “packs up

in two days”; while in marriage the partners “let themselves go” and “stop caring”.

Getting married carries the risk of falling into a “routine” and a “gray reality”, while

cohabitation resembles dating in some respects. The assumption that cohabiting

partners have to make an effort to please each other was appealing to some of the

respondents, both men and women.

Moreover, the fear of “routine” was mentioned by a number of the respondents

when they were asked why some people continue to cohabit for a long time and do not

get married. While the dominant reaction to this question was that these couples believe

that they “do not need a piece of paper”, several participants spoke of a possible fear

that getting married would negatively affect the relationship, as in the following

examples:

If everything is ok, this wedding is not really needed, because it‟s all good.

Maybe they are afraid of getting into a routine, getting bored of each other.

(FG7, woman, highly educated)

Sometimes they may be afraid that this piece of paper will change something

for the worse. A kind of commitment to be together for the rest of their lives,

it‟s like being condemned to be with each other. This pressure of time, I‟m

afraid it is counterproductive. (FG4, woman, low/medium educated)

6. Summary and discussion

While the diverging dynamics of the diffusion of cohabitation across European societies

are very well documented (Heuveline and Timberlake 2004; Sobotka and Toulemon

2008), the underlying mechanisms beyond the different speeds at which this diffusion is

occurring are much less understood. We know very little about how couples think and

feel about the advantages and disadvantages of choosing specific living arrangements,

and how these views translate into the frequency of cohabitation. In this article we have

provided some insight into people‟s perceptions and attitudes regarding non-marital

unions, with a focus on one of the key characteristics of cohabitation: freedom in a

relationship.

Demographic Research: Volume 31, Article 36

http://www.demographic-research.org 1125

Our results suggest that freedom in a partnership has a number of important

dimensions. According to our respondents, cohabitation offers considerable freedom to

leave at any time with few repercussions. This is primarily because cohabitation does

not entail a legal bond, but also because partners in informal unions are assumed to

have a reduced sense of moral obligation and a higher degree of independence. It is

apparent that consensual unions are perceived as being less committed and less stable.

But the respondents cited several reasons why this might in fact be beneficial, even in

the context of relationship development.

According to the respondents, the biggest advantage of cohabitation is that it offers

relaxed conditions for testing a relationship. The respondents see the testing role of

cohabitation as being very important. Living together allows the partners to make more

informed choices regarding their relationship and improves their chances of having a

happy marriage. As the negative aspects of divorce were widely discussed and were

clearly characterized as being undesirable, it appears that pre-marital cohabitation is

seen as a way of „divorce-proofing‟ a marriage. In fact, most of the recent studies that

have controlled for selection into cohabitation of people in poor-quality relationships

(i.e., relationships with a high propensity to dissolve because of unobserved

characteristics of the partners) have shown that marriages formed by previously

cohabiting partners are less likely to be disrupted than those that are not preceded by

non-marital cohabitation (Kulu and Boyle 2010; Reinhold 2010; Manning and Cohen

2012). Living together is therefore an important stage in the relationship development

process. The belief that cohabitation is very easy to terminate strongly encourages

young adults to make use of this stage. Our interviewees perceive living together as

being a risk-free (or at least low-risk) opportunity to avoid making serious life mistakes,

and especially to avoid having to endure the financially and emotionally exhausting

legal proceedings associated with divorce. Consequently, people are increasingly

willing to enter into pre-marital cohabitation arrangements. The respondents

acknowledged this explicitly, saying that the testing role of cohabitation is the most

important reason why non-marital unions have become more common in Poland.

This is the central, but not the only benefit of the freedom associated with

cohabitation that the participants in the study commented upon. Our respondents

observed that the awareness that each partner can leave the union easily can make living

together somewhat more exciting, at least for some individuals. According to the

interviewees, it may motivate the partners to remain attractive to each other, and to

avoid falling into a dull routine. Apparently, cohabitation is perceived as being a period

of courting, when people are committed to showing their best side to their partner. It is

assumed that the partners will make an effort to keep their relationship interesting,

precisely because it is fragile and easy to dissolve. Some may even fear the transition to

marriage because, in addition to stability, it might bring stagnation, routine, and

Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak: Freedom in cohabitation in Poland

1126 http://www.demographic-research.org

unwelcome changes in the partner‟s behavior. To the best of our knowledge, none of

the previous qualitative studies on the advantages and disadvantages of cohabitation has

found that this feature of cohabitation can be perceived as being attractive. In fact, two

studies – one conducted in the US (Huang et al. 2011) and one in Norway (Reneflot

2006) – have found that romantic love is more likely to be extinguished when a couple

starts living together.

In addition, some of the women respondents argued that one advantage of

cohabitation is that, unlike in marriage, the female partner is not expected to take over

the household duties. This egalitarian feature of cohabitation makes it attractive to some

women, but it should be stressed that this issue was mentioned in only two focus

groups.

Clearly, the results from this study indicate that the respondents feel some

ambivalence about marital commitment, as marriage might bring stagnation and routine

and could impose traditional gender roles on women. This ambivalence was not

dominant in the responses in the current study, but it was completely absent in the

qualitative in-depth interviews conducted eight years ago with individuals with similar

demographic characteristics (Mynarska and Bernardi 2007). Interestingly, in the

previous study some respondents challenged the testing role of cohabitation, while

marital commitment was universally evaluated as being positive and desirable. In the

current inquiry, carried out almost a decade later, there seems to have been a slight shift

in attitudes: the respondents acknowledged the probationary role of pre-marital unions,

while pointing out a few cracks in the perfect image of marriage. As the respondents in

both of these studies were urban and relatively young, future quantitative investigations

should examine whether the pattern we observed reveals a more general shift in

attitudes in Polish society.

While the freedom offered by cohabitation was evaluated positively, most of the

respondents agreed that an informal union is not the right context for childbearing.

Because cohabitation is easy to terminate, cohabiting couples do not accumulate joint

possessions and avoid situations in which one of the partners – usually the woman –

becomes economically dependent on the other party. As long as couples are childless,

this economic freedom may be appreciated. But a young cohabiting mother might feel

pressured to remain economically independent of her partner. In the Polish context, a

woman may perceive this financial independence as being threatening when she wishes

to become a mother. In Poland the options for couples with small children of dividing

up the tasks within and outside of the household are limited. The conditions for

combining work and family duties are poor, and conservative attitudes toward gender

roles continue to prevail (Lück and Hofäcker 2003; Matysiak and Węziak-Białowolska

2013). Consequently, it is assumed that a mother and her children will depend to a large

extent on the male partner‟s income. As the law does not recognize cohabitation and the

Demographic Research: Volume 31, Article 36

http://www.demographic-research.org 1127

rights and obligations of partners are not legally established, this arrangement is

considered too insecure for childbearing. The respondents recognized this insecurity,

emphasizing repeatedly that non-marital cohabitation is positive only if it is a temporary

arrangement, and that the union should be formalized if the trial period of cohabitation

is successful.

All in all, our study showed that there are a number of important aspects of

cohabitation that are perceived as advantages. It suggests that pre-marital cohabitation

may be increasingly attractive precisely because it does not require a strong

commitment: specifically, that the open nature of cohabitation offers good conditions

for partners to test out their relationship, while avoiding falling into a routine or a non-

egalitarian division of gender roles. Nonetheless, as long as cohabitation remains an

incomplete institution – unrecognized by law and accepted reluctantly by society – and

does not provide secure conditions for childrearing, it is likely to remain a temporary

living arrangement.

We hypothesize, however, that not only the frequency but also the duration of

cohabitation is likely to increase. As long as parenthood is not planned, the benefits of

cohabitation that are related to freedom in a relationship may be seen as outweighing

the disadvantages. Consequently, some childless couples might choose to remain

unmarried until they decide to have a child, even if they believe that their relationship

has been sufficiently tested. As Poles increasingly postpone parenthood and choose to

remain childless it is likely that the decision to marry will continue to shift to later ages,

resulting in longer periods of cohabitation. These hypotheses should be carefully tested

in future quantitative studies, and decision-making processes about cohabitation and

marriage should be further examined in qualitative interviews.

Our study shows that a more in-depth explication of the meaning of freedom is

important for understanding the role cohabitation plays in society. We have shown that

freedom is a complex and multidimensional concept. In other contexts the uncommitted

nature of informal unions will be seen differently, and other aspects of freedom will be

stressed (compare Perelli-Harris et al. 2014). Understanding this diversity is important

in explaining the differences in the nature of cohabitation across countries.

Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak: Freedom in cohabitation in Poland

1128 http://www.demographic-research.org

7. Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Brienna Perelli-Harris‟s ERC CHILDCOHAB starting

grant during the period 2011–2013 and by the National Centre of Research and

Development (Poland) within the research project “Family Change and Subjective

Well-Being” (FAMWELL) financed under the Programme LIDER. We are very

grateful to Paulina Trevena, who moderated the FGs and performed the first round of

coding of the material. The article benefited from discussions with Focus on Partnership

team members during workshops. We are grateful to Brienna Perelli-Harris, Laura

Bernardi and two anonymous reviewers of Demographic Research for their valuable

comments.

Demographic Research: Volume 31, Article 36

http://www.demographic-research.org 1129

References

Aassve A., Sironi M., and Bassi V. (2013). Explaining Attitudes Towards Demographic

Behaviour. European Sociological Review 29(2): 316–333. doi:10.1093/esr/jcr

069.

Adams, J.M. and Jones, W.H. (1997). The conceptualization of marital commitment:

An integrative analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 72(5):

1177–1196. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.5.1177

Baxter, J. (2005). To Marry or Not to Marry: Marital Status and the Household Division

of Labor. Journal of Family Issues 26(3): 300–321. doi:10.1177/0192513X0427

0473.

Baxter, J., Haynes, M., and Hewitt, B. (2010). Pathways Into Marriage: Cohabitation

and the Domestic Division of Labor. Journal of Family Issues 31(11): 1507–

1529. doi:10.1177/0192513X10365817.

Bowman, C.G. (2004). Legal Treatment of Cohabitation in the United States. Law &

Policy 26(1): 119–151. doi:10.1111/j.0265-8240.2004.00165.x.

Bradley, D. (2001). Regulation of unmarried cohabitation in west-European

jurisdictions - determinants of legal policy. International Journal of Law, Policy

and the Family 15(1): 22–50. doi:10.1093/lawfam/15.1.22.

Brines, J. and Joyner, K. (1999). The ties that bind: Principles of cohesion in

cohabitation and marriage. American Sociological Review 64(3): 333–355.

doi:10.2307/2657490.

Casper, L.M. and Bianchi, S.M. (2002). Continuity and change in the American family.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cherlin, A. (2000). Towards a new home socioeconomics of union formation. In:

Waite, L.J., Bachrach, C.A., Hindin, M.J., Thomson, E., and Thornton, A. (eds.).

The ties that bind: Perspectives on cohabitation and marriage. New York:

Aldine de Gruyter: 126–146.

Cherlin, A.J. (2009). The marriage-go-round: The state of marriage and the family in

America today. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Clarkberg, M., Stolzenberg, R.M., and Waite, L.J. (1995). Attitudes, Values, and

Entrance into Cohabitational versus Marital Unions. Social Forces 74(2): 609–

632. doi:10.1093/sf/74.2.609.

Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak: Freedom in cohabitation in Poland

1130 http://www.demographic-research.org

Cohan, C.L. and Kleinbaum, S. (2002). Toward a Greater Understanding of the

Cohabitation Effect: Premarital Cohabitation and Marital Communication.

Journal of Marriage and Family 64(1): 180–192. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.

00180.x.

Corijn, M. and Manting, D. (2000). The Choice of Living Arrangement after Leaving

the Parental Home. In: de Beer, J. and Deven, F. (eds.). Diversity in Family

Formation. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands: 33–58. doi:10.1007/978-94-015-

9512-4_3.

CSO (2013). Rocznik demograficzny 2013. Warsaw: Zakład Wydawnictw

Statystycznych.

Davis, S.N., Greenstein, T.N., and Gerteisen Marks, J.P. (2007). Effects of Union Type

on Division of Household Labor. Journal of Family Issues 28(9): 1246–1272.

doi:10.1177/0192513X07300968.

Drewianka, S. (2004). How Will Reforms of Marital Institutions Influence Marital

Commitment? A Theoretical Analysis. Review of Economics of the Household

2(3): 303–323. doi:10.1007/s11150-004-5649-3.

Drewianka, S. (2006). A generalized model of commitment. Mathematical Social

Sciences 52(3): 233–251. doi:10.1016/j.mathsocsci.2006.03.010.

Glaser, B.G. (1965). The Constant Comparative Method of Qualitative Analysis. Social

Problems 12(4): 436–445. doi:10.2307/798843.

Glaser, B.G. and Strauss, A.L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for

qualitative research (Observations). Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co.

Grossbard-Shechtman, A. (1982). A Theory of Marriage Formality: The Case of

Guatemala. Economic Development and Cultural Change 30(4): 813–830.

doi:10.1086/452591.

Grossbard-Shechtman, S. (1993). On the economics of marriage: a theory of marriage,

labor, and divorce. Boulder: Westview Press.

Heimdal, K.R. and Houseknecht, S.K. (2003). Cohabiting and Married Couples' Income

Organization: Approaches in Sweden and the United States. Journal of Marriage

and Family 65(3): 525–538. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00525.x.

Heuveline, P. and Timberlake, J.M. (2004). The Role of Cohabitation in Family

Formation: The United States in Comparative Perspective. Journal of Marriage

and Family 66(5): 1214–1230. doi:10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00088.x.

Demographic Research: Volume 31, Article 36

http://www.demographic-research.org 1131

Hiekel, N., Liefbroer, A.C., and Poortman, A.-R. (2014). Income pooling strategies

among cohabiting and married couples: A comparative perspective.

Demographic Research 30(55): 1527–1560. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2014.30.55.

Hoem, J.M., Gabrielli, G., Jasilioniene, A., Kostova, D., and Matysiak, A. (2010).

Levels of recent union formation: Six European countries compared.

Demographic Research 22(9): 199–210. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2010.22.9.

Hogerbrugge, M.J.A. and Dykstra, P.A. (2009). The Family Ties of Unmarried

Cohabiting and Married Persons in the Netherlands. Journal of Marriage and

Family 71(1): 135–145. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00585.x.

Hsueh, A.C., Morrison, K.R., and Doss, B.D. (2009). Qualitative reports of problems in

cohabiting relationships: Comparisons to married and dating relationships.

Journal of Family Psychology 23(2): 236–246. doi:10.1037/a0015364.

Huang, P.M., Smock, P.J., Manning, W.D., and Bergstrom-Lynch, C.A. (2011). He

Says, She Says: Gender and Cohabitation. Journal of Family Issues 32(7): 876–

905. doi:10.1177/0192513X10397601.

Kasearu, K. and Kutsar, D. (2011). Patterns behind unmarried cohabitation trends in

Europe. European Societies 13(2): 307–325. doi:10.1080/14616696.2010.4935

86.

Kiernan, K.E. (2004). Unmarried Cohabitation and Parenthood in Britain and Europe.

Law & Policy 26(1): 33–55. doi:10.1111/j.0265-8240.2004.00162.x.

Kline, G.H., Stanley, S.M., Markman, H.J., Olmos-Gallo, P.A., St. Peters, M., Whitton,

S.W., and Prado, L.M. (2004). Timing Is Everything: Pre-Engagement

Cohabitation and Increased Risk for Poor Marital Outcomes. Journal of Family

Psychology 18(2): 311–318. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.311.

Kulu, H. and Boyle, P. (2010). Premarital cohabitation and divorce: Support for the

“Trial Marriage” Theory? Demographic Research 23(31): 879–904. doi:10.40

54/DemRes.2010.23.31.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The Unfolding Story of the Second Demographic Transition.

Population and Development Review 36(2): 211–251. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.

2010.00328.x.

Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak: Freedom in cohabitation in Poland

1132 http://www.demographic-research.org

Liefbroer, A.C. and Fokkema, T. (2008). Recent trends in demographic attitudes and

behaviour: Is the Second Demographic Transition moving to Southern and

Eastern Europe? In: Surkyn, J., Deboosere, P., and van Bavel, J. (eds.).

Demographic challenges for the 21st century. A state of the art in demography.

Brussel: Vrije Universiteit Press: 115–141.

Lindsay, J.M. (2000). An ambiguous commitment: Moving in to a cohabiting

relationship. Journal of Family Studies 6(1): 120–134. doi:10.5172/jfs.6.1.120.

Lück, D. and Hofäcker, D. (2003). Rejection and acceptance of the male breadwinner

model: Which preferences do women have under which circumstances.

Globalife Working Paper 60. Bamberg: Otto-Friedrich University of Bamberg.

Lyngstad, T.H., Noack, T., and Tufte, P.A. (2011). Pooling of Economic Resources: A

Comparison of Norwegian Married and Cohabiting Couples. European

Sociological Review 27(5): 624–635. doi:10.1093/esr/jcq028.

Manning, W.D. and Cohen, J.A. (2012). Premarital Cohabitation and Marital

Dissolution: An Examination of Recent Marriages. Journal of Marriage and

Family 74(2): 377–387. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00960.x.

Manning, W.D. and Smock, P.J. (2005). Measuring and Modeling Cohabitation: New

Perspectives From Qualitative Data. Journal of Marriage and Family 67(4):

989–1002. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00189.x.

Matysiak, A. (2009). Is Poland really „immune‟ to the spread of cohabitation?,

Demographic Research 21(8): 215–234. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2009.21.8.

Matysiak, A. and Węziak-Białowolska, D. (2013), Country-specific conditions for work

and family reconciliation: An attempt at quantification. ISD Working Paper 31.

Warsaw: Institute of Statistics and Demography, Warsaw School of Economics.

Matysiak, A. and Mynarska, M. (2014). Urodzenia w kohabitacji: wybór czy

konieczność? In: Matysiak, A. (ed.). Nowe wzorce formowania i rozwoju

rodziny w Polsce. Przyczyny oraz wpływ na zadowolenie z życia. Warsaw:

Scholar: 24–53.

Matysiak, A. and Wrona, G. (2010). Regulacje prawne tworzenia, rozwoju i rozpadu

rodzin w Polsce. ISD Working Paper 8. Warsaw: Institute of Statistics and

Demography, Warsaw School of Economics.

Murrow, C. and Shi, L. (2010). The influence of cohabitation purposes on relationship

quality: an examination in dimensions. American Journal of Family Therapy

38(5): 397–412. doi:10.1080/01926187.2010.513916.

Demographic Research: Volume 31, Article 36

http://www.demographic-research.org 1133

Mynarska, M. and Bernardi, L. (2007). Meanings and attitudes attached to cohabitation

in Poland: Qualitative analyses of the slow diffusion of cohabitation among the

young generation. Demographic Research 16(17): 519–554. doi:10.4054/Dem

Res.2007.16.17.

Mynarska, M. and Matysiak, A. (2010). Diffusion of cohabitation in Poland. Studia

Demograficzne 1–2/157–158: 11–25.

Nock, S.L. (1995). A Comparison of Marriages and Cohabiting Relationships. Journal

of Family Issues 16(1): 53–76. doi:10.1177/019251395016001004.

Perelli-Harris, B. and Gassen, N.S. (2012). How Similar Are Cohabitation and

Marriage? Legal Approaches to Cohabitation across Western Europe.

Population and Development Review 38(3): 435–467. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.

2012.00511.x.

Perelli-Harris, B., Kreyenfeld, M., Sigle-Rushton, W., Keizer, R., Lappegård, T.,

Jasilioniene, A., Berghammer, C., and Di Giulio, P. (2012). Changes in union

status during the transition to parenthood in eleven European countries, 1970s to

early 2000s. Population Studies 66(2): 167–182. doi:10.1080/00324728.2012.

673004.

Perelli-Harris, B., Sigle-Rushton, W., Kreyenfeld, M., Lappegård, T., Keizer, R., and

Berghammer, C. (2010). The educational gradient of childbearing within

cohabitation in Europe. Population and Development Review 36(4): 775–801.

doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00357.x.

Perelli-Harris, B., Mynarska, M., Berrington, A., Evans, A., Berghammer, C., Isupova,

O., Keizer, R., Klärner, A., Lappegård, T., and Vignoli, D. (2014). Towards a

new understanding of cohabitation: Insights from focus group research across

Europe and Australia. Demographic Research 31(34): 1043–1078.

doi:10.4054/DemRes.2014.31.34.

Pongracz, M. and Spéder, Z. (2008). Attitudes towards forms of partnership. In: Höhn,

C., Avramov, D., and Kotowska, I.E. (eds.). People, population change and

policies: Lessons from the Population Policy Acceptance Study. Berlin:

Springer: 93–112. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6609-2_5.

Poortman, A.-R. and Mills, M. (2012). Investments in Marriage and Cohabitation: The

Role of Legal and Interpersonal Commitment. Journal of Marriage and Family

74(2): 357–376. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00954.x.

Ramsøy, N.R. (1994). Non-marital Cohabitation and Change in Norms: The Case of

Norway. Acta Sociologica 37(1): 23–37. doi:10.1177/000169939403700102.

Mynarska, Baranowska-Rataj & Matysiak: Freedom in cohabitation in Poland

1134 http://www.demographic-research.org

Reinhold, S. (2010). Reassessing the link between premarital cohabitation and marital

instability. Demography 47(3): 719–733. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0122.

Reneflot, A. (2006). A gender perspective on preferences for marriage among

cohabitating couples. Demographic Research 15(10): 311–328. doi:10.4054/

DemRes.2006.15.10.

Rhoades, G.K., Stanley, S.M., and Markman, H.J. (2009). The pre-engagement

cohabitation effect: A replication and extension of previous findings. Journal of

family psychology 23(1): 107–111. doi:10.1037/a0014358.

Rindfuss, R.R. and VandenHeuvel, A. (1990). Cohabitation: A Precursor to Marriage or

an Alternative to Being Single? Population and Development Review 16(4):

703–726. doi:10.2307/1972963.

Sassler, S. (2004). The Process of Entering into Cohabiting Unions. Journal of

Marriage and Family 66(2): 491–505. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2004.00033.x.

Seltzer, J.A. (2000). Families Formed Outside of Marriage. Journal of Marriage and

Family 62(4): 1247–1268. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01247.x.

Shapiro, A. and Keyes, C.L.M. (2008). Marital Status and Social Well-Being: Are the

Married Always Better Off? Social Indicators Research 88(2): 329–346. doi:10.

1007/s11205-007-9194-3.

Sobotka, T. and Toulemon, L. (2008). Changing family and partnership behaviour:

Common trends and persistent diversity across Europe. Demographic Research

19(6): 85–138. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.6.

Soons, J.P.M. and Kalmijn, M. (2009). Is Marriage More Than Cohabitation? Well-

Being Differences in 30 European Countries. Journal of Marriage and Family

71(5): 1141–1157. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00660.x.

Stępień-Sporek, A. and Ryznar, M. (2010). The legal treatment of cohabitation in

Poland and the United States. UMKC Law Review 79(2): 373–393.

Styrc, M. (2010). Czynniki wpływające na stabilność pierwszych małżeństw w Polsce.

Studia Demograficzne 1–2/157–158: 27–59.

Surkyn, J. and Lesthaeghe, R. (2004). Value Orientations and the Second Demographic

Transition (SDT) in Northern, Western and Southern Europe: An Update.