239

Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research • Volume 17, Number 2 • 2015

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development • Office of Policy Development and Research

Cityscape

Foreclosed Property Investors

in a Strong Housing Market

City: A Case Study of Boston

Lauren Lambie-Hanson

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Christopher E. Herbert

Irene Lew

Rocio Sanchez-Moyano

Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University

Abstract

Falling home sales prices during the recent mortgage crisis were exacerbated by an

increased number of properties coming on the housing market through foreclosures and

short sales. Real estate investors made up a significant share of buyers of foreclosed

residential properties in cities around the country, leading many to ask if, on net, they

provide a stabilizing influence on the market or are detrimental. In this case study, we

explore the scale and nature of investor activity in acquiring foreclosed properties in the

heart of the Boston area. We find that investors purchased about one-half of foreclosed

properties. Despite competition from owner-occupants and mission-driven organizations,

investors were successful in purchasing such a large share of foreclosed properties because

of several characteristics we discuss, particularly their greater access to financing and

ability to pay cash. Although opportunities for favorable returns on investment encourage

investors to purchase homes in the most distressed neighborhoods and to make property

improvements, investors may not pursue the most severely distressed foreclosed

properties or perform the degree of rehabilitation desired by nonprofit organizations.

Introduction

When the housing bust accelerated in 2008, concerns mounted about the effect of rising foreclo-

sure levels, especially in low-income and minority communities where nonprime lending had been

concentrated in the years leading up to the crash. With demand from owner-occupants in these

240

Lambie-Hanson, Herbert, Lew, and Sanchez-Moyano

Refereed Papers

communities plummeting in tandem with rising unemployment and falling home prices, market

analysts expected that foreclosed homes would find few buyers. In fact, although owner-occupant

demand remained weak in areas hard hit by foreclosures, many housing markets experienced a

surge of home purchases by investors absorbing excess supply.

Although the prominence of investors’ presence has received substantial interest, little systematic

assessment has occurred regarding the scale of investor activity, which properties investors acquire,

and what they do with them. This study aims to investigate these topics in one area as a means of

shedding light on how investors are likely to affect local housing markets. This case study focuses

specifically on investor activity in the city of Boston and three other jurisdictions in Suffolk County,

Massachusetts.

We analyze data on foreclosed properties in Suffolk County from 2007 to 2012 to provide a quan-

titative assessment of investor activity. We supplement this analysis with information obtained from

a small sample of interviews with market participants in Boston, including government officials,

staff from nonprofit organizations, real estate brokers, lenders, and investors to paint a portrait of

investors and their activities. Although the number of interviews conducted was limited and only

a small number of investors participated, the results provide some indication of the characteristics,

motivations, and activities of investors to help inform our understanding of how investors have

affected local markets.

Since the housing market downturn began in 2007, investors have played a significant role in ac-

quiring foreclosed properties in Suffolk County, accounting for 44 percent of foreclosed properties

sold at foreclosure auction or out of real estate owned (REO) inventories from 2007 through 2012.

Three-fourths of the investors we identified acquired only three or fewer foreclosed properties in

Suffolk County. Meanwhile, only 7 percent of all investors (totaling 33 different entities) acquired

10 or more foreclosed properties between 2007 and 2012 but accounted for one-half of all investor

foreclosed property acquisitions. Although these large investors acquired properties in neighbor-

hoods throughout Suffolk County, they were more active in neighborhoods with high foreclosure

rates, relatively low median home prices and household incomes, and a large share of households

headed by racial and ethnic minorities. Given the significance of their role in these neighborhoods,

this study largely focuses on the activities of these large investors.

Toward the end of the period we study, mortgage default rates had begun falling and fewer fore-

closed properties came onto the market. Meanwhile, more investors entered the market, driving

up competition for acquiring foreclosed properties. Several investors told us that the prices of

properties sold out of REO and at auction rose substantially over time, even after taking into ac-

count property condition and other characteristics. Despite this increased cost, foreclosed property

investors still bought about one-half of the foreclosed properties sold in Suffolk County in 2012.

Part of the scale of investor activity can be explained by heterogeneous preferences between the

different types of buyers. Investors were active in areas with high foreclosure rates and often had

stronger tastes for distressed housing than most owner-occupants, who are generally assumed to

seek out turnkey properties. Despite this trend, we learned from our interviews that investors faced

competition from nonprofit organizations for distressed properties, and they also competed to buy

move-in-ready properties. We argue that three main characteristics of investors set them apart from

Foreclosed Property Investors in a Strong Housing Market City:

A Case Study of Boston

241Cityscape

other types of buyers: (1) their willingness and ability to purchase at foreclosure auction; (2) their

connections to other real estate professionals; and (3) their greater access to financing, including

their ability to pay cash.

Although much has been made of the significant role that national investment funds and foreign

investors have played in acquiring foreclosed properties in some parts of the country, the large

investors active in Suffolk County for the most part have local roots—at least as of 2012. Some of

these large investors had a long history of owning rental properties in Boston, while others were

new to the market, attracted by the opportunity to acquire properties at lower-than-normal price

points through foreclosure sales. The predominant strategy among large investors in Boston has

been to hold on to these foreclosed properties as rental units. But the spectrum of large investor

strategies has also included those who sold most of their purchases, and others who were roughly

divided in the share held versus the share resold. The lack of a consistent tendency to hold or sell

properties indicates that, in many respects, investors pursued property-specific strategies.

Given that foreclosed properties have often gone through a period of neglect, and so their presence

may exert a blighting influence on the surrounding neighborhood, a key policy concern is whether

investors engage in rehabilitation of properties to any significant degree. Although this study does

not attempt to systematically measure the degree of rehabilitation investors undertake, we argue

that Boston’s relatively high housing values and significant rental demand provide incentives for

investors to maintain these properties in at least decent condition.

That said, we learned from our interviews that investors did not make property improvements to

the extent that nonprofit organizations felt was desirable. This difference likely reflects the fact that

nonprofit organizations were pursuing broader goals of neighborhood revitalization with the sup-

port of government subsidies, while investors’ decisions about the degree of investment to make

were driven purely by expectations of higher rents or resale values.

The article proceeds as follows. In the next section, we briefly review the existing literature on the

role of private investors in acquiring foreclosed properties in cities around the United States. Then

we provide an overview of housing market conditions and demographic traits of Suffolk County,

the focus of this study. In the third section we describe the methods used in our analysis and docu-

ment the scale of investor activity and the characteristics of the neighborhoods in which investors

are most active. In the fourth section we describe the ways in which investors successfully compete

to purchase foreclosed properties. Then we discuss their decisions to resell or hold properties and

whether to make property improvements. We finally summarize our findings and discuss their

likely applicability to other cities.

Previous Research About Investors

To address the policymakers’ and academic communities’ growing interest in foreclosed property

investors, this study and three others were commissioned to explore investor behavior in four

cities: (1) Boston, Massachusetts; (2) Atlanta, Georgia; (3) Cleveland, Ohio; and (4) Las Vegas,

Nevada. Immergluck and Law (2014) compared and contrasted the behavior of foreclosed single-

family home investors in Atlanta and the surrounding suburbs in Fulton County, Georgia, tracking

242

Lambie-Hanson, Herbert, Lew, and Sanchez-Moyano

Refereed Papers

their behavior from 2002 to 2011. The investors they interviewed had moderate to high levels of

spending on renovations, particularly relative to the low property acquisition costs in the area, and

respondents indicated that they were either content with or eager for even stricter code enforcement.

Ford et al. (2013) found more evidence of problematic investor behavior in Cleveland. Although

institutional investors tended to avoid investing in central city neighborhoods, out-of-state

investors (primarily noninstitutional) who purchased in these neighborhoods were likely to

underestimate the costs required to stabilize and renovate the deteriorated properties. Mallach

(2014) studied single-family home and condominium foreclosures in four ZIP Codes in Las Vegas

and argued that foreclosed property investors provided a stabilizing influence in those neighbor-

hoods, but that, over time, investors increasingly crowded out prospective owner-occupants. After

conducting windshield surveys of a sample of properties in his study area, Mallach concluded

that investor-owned properties had poorer exterior conditions but were not so inadequate as to be

considered blights in the immediate neighborhoods. Similar to Boston, relatively few investors in

Las Vegas purchased many properties.

1

Using a similar approach, Ellen, Madar, and Weselcouch (2014) examined data on sales of foreclosed

properties in Atlanta, Miami, and New York City, and found that investors played a large role in

purchasing REO properties in these cities. In Atlanta, investors were most active in moderately hit

neighborhoods, although, in Miami and New York, they were more commonly active in neighbor-

hoods with the most distressed properties. In all three cities, small-scale investors made up more

than two-thirds of the investor REO purchases, and few purchases by investors resulted in “flips.”

Treuhaft, Rose, and Black (2011) reviewed research from the 1990s and argued that large, nonlocal

investors, particularly those who purchase properties in bulk, were less desirable than homeowners and

small, local investors who are committed to property rehabilitation. Fisher and Lambie-Hanson (2012)

analyzed data on the purchases and investment behaviors of investor-owners and owner-occupants

in Chelsea, one of the cities in Suffolk County, Massachusetts. Basing their analysis on building permits

data, they found that local investors purchasing one- to three-family homes before the foreclosure

crisis planned to make greater investments than owner-occupants and nonlocal investors. Although

local press reports (for example, McKim, 2008) suggested that several large local investors in our sample

were slow to make improvements to the foreclosed properties they purchased, evidence from our

interviews indicates that numerous local REO investors spent a substantial amount on rehabilita-

tion. We discuss this issue in greater detail in the section Postpurchase Property Management.

Treuhaft, Rose, and Black (2011) stressed that, because investors disproportionately purchased dam-

aged REO properties, the business models they use are crucial to determining their effect on neighbor-

hoods. Numerous scholars have turned to Mallach’s (2010a) typology of foreclosed property investors

as rehabbers, flippers, milkers, and holders. We discuss these groups in the section Postpurchase

Property Management. King (2012) found evidence of all four investor types in Oakland, California,

between 2007 and 2011. During that time, investors made up nearly one-half of all foreclosed property

purchases, which is similar to the share in Suffolk County, Massachusetts. King expressed some surprise

that investors did not capture an even greater share, considering “the competitive advantage that cash

investors wield at multiple stages in the post-foreclosure home buying landscape” (King, 2012: 5).

1

For a comprehensive summary and comparison of the four case studies, see Herbert, Lew, and Sanchez-Moyano (2013).

Foreclosed Property Investors in a Strong Housing Market City:

A Case Study of Boston

243Cityscape

Although maintaining a strategy to hold may be potentially desirable from a neighborhood perspective,

it may be prohibitively expensive from the perspective of profit-motivated investors—particularly

those supplying housing at affordable rents. Typical rehabilitation costs for foreclosed properties

may be infeasible for many owners, given that profit margins for small rental properties are often

slim. Mallach (2007) wrote that, in 1995, less than 40 percent of the owners of one- to four-family

rental properties reported that they had made a profit on their property during the preceding year.

An analysis of data from the 2001 Residential Finance Survey and the 2007 American Housing Sur-

vey by Garboden and Newman (2012) tells a similar story. Their study found that only 5 percent of

small (one- to four-unit) affordable rental properties, which are typically owned by individuals or

couples, were in economically stable condition. More than one-half (65 percent) of the units could

have been salvaged but were at risk of losing affordability, and 30 percent could not be salvaged.

Trends and Conditions in the Boston Housing Market

The specific focus of this study is on foreclosed properties in Suffolk County, the core county of

the Boston metropolitan area, consisting of the cities of Boston, Chelsea, Revere, and Winthrop.

Although not as dramatic as in some U.S. housing markets, Suffolk County experienced a sub-

stantial housing boom and bust during the 2000s. From the start of the decade through the peak

in November 2005, home sales prices in Suffolk County increased 86 percent. National prices

continued to climb into 2006, however. After the peak, prices in Suffolk County began a steady

decline, bottoming out in March 2009 at about 29 percent below peak values. Nationwide, during

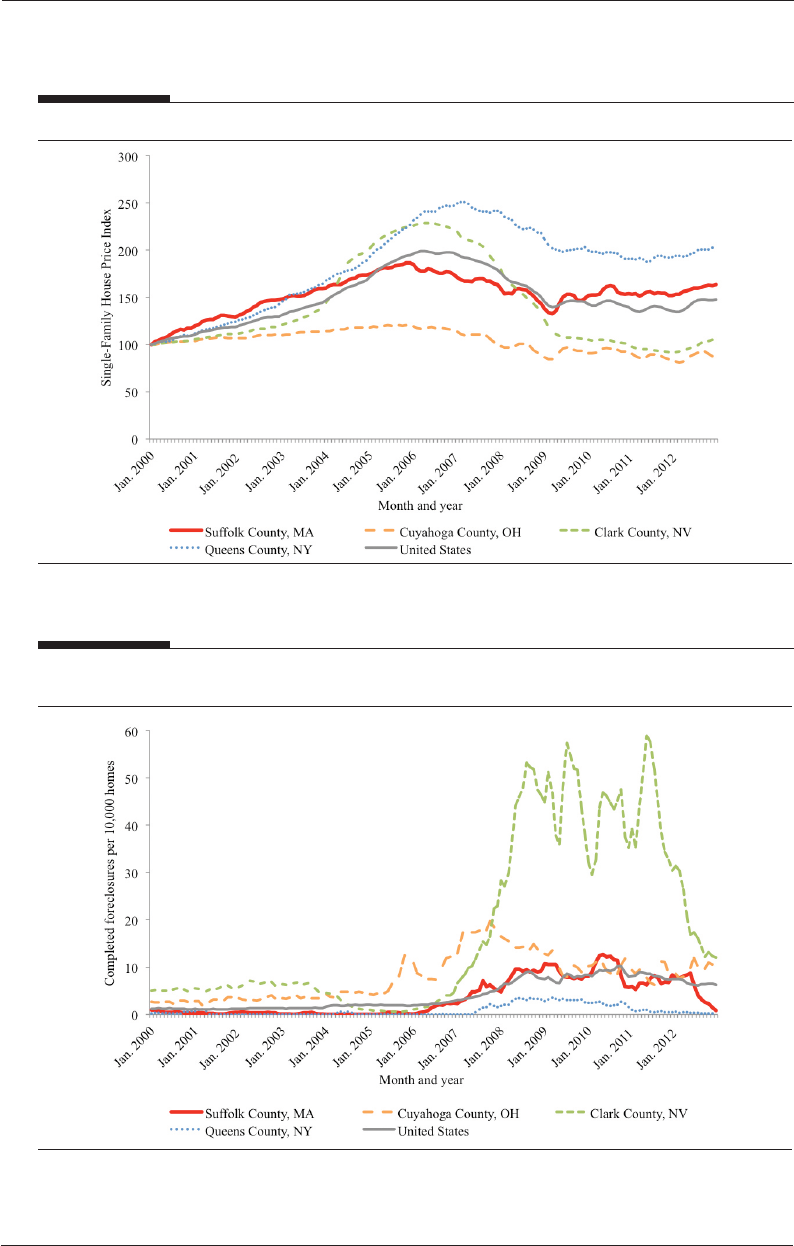

the same period, prices declined 28 percent. In exhibit 1 we display Suffolk County’s house price

index, along with the national index and the indices for Cuyahoga County (Cleveland), Clark

County (Las Vegas), and Queens County (in New York City). As discussed in the previous section,

these three places have also been the subject of foreclosed property investor case studies.

2

Clark

County experienced both a dramatic increase and subsequent decline in house prices in the 2000s.

In Queens, prices also rose rapidly and then fell, although the decline was far less severe than that

of Las Vegas. Cuyahoga County experienced very little growth in prices from 2000 to 2005, and

while prices did decline beginning in 2006, the reduction was also comparatively small.

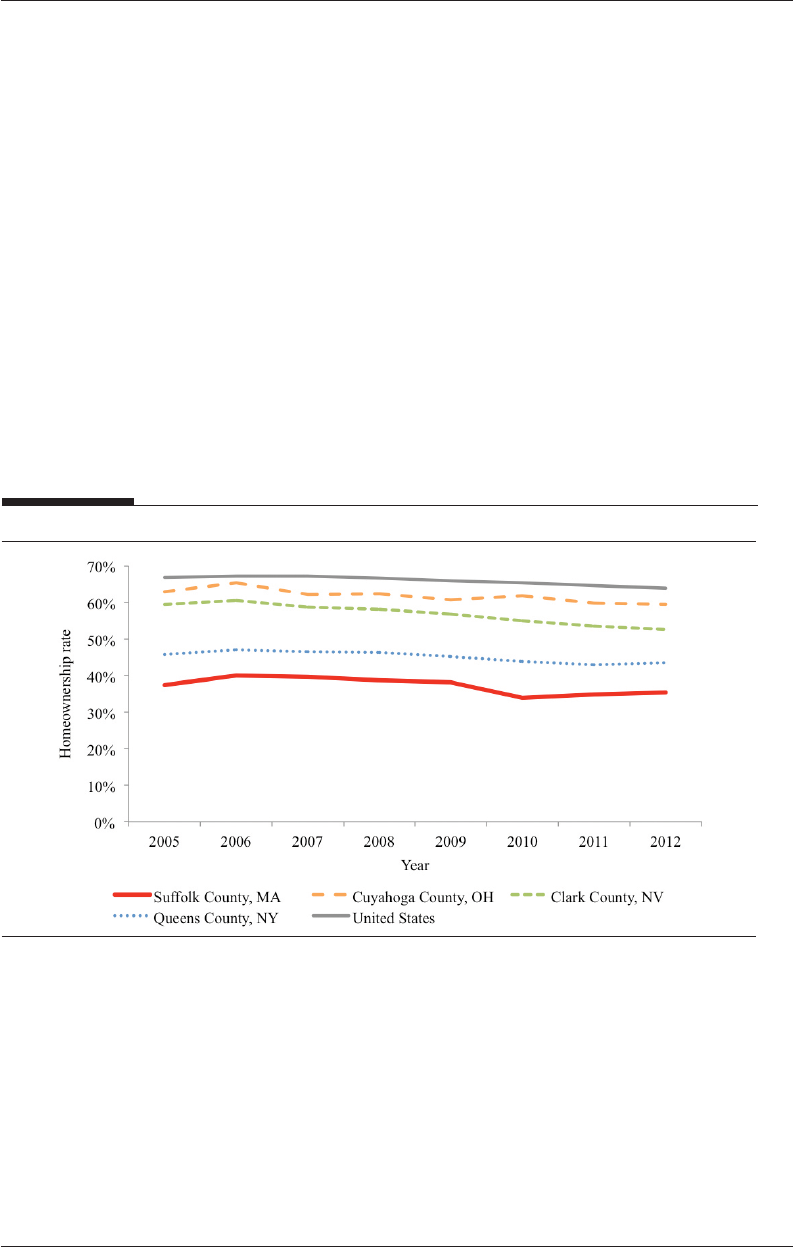

Coinciding with falling house prices, Suffolk County saw a large increase in the number of

foreclosed properties.

3

As shown in exhibit 2, during May 2010, the height of its foreclosure crisis,

Suffolk County experienced 12.7 foreclosures per 10,000 homes. From 2009 through mid-2012,

Suffolk County’s rate of foreclosure completions was very similar to the national rate and to the rate

for Cuyahoga County. Cleveland’s foreclosure crisis began in 2005, however, well before most of

the rest of the country. As of the end of 2012, it had also shown less improvement than other areas.

But all the places profiled in exhibit 2 had foreclosure rates that paled in comparison with that

of Las Vegas, where in May 2011, nearly 59 foreclosures occurred per 10,000 homes. Since then,

however, Las Vegas has seen rapid improvement. In December 2012, only 12 foreclosures were

completed per 10,000 homes.

2

Among all the places discussed in the section Previous Research About Investors, these areas were chosen because of the

availability of Zillow foreclosure data, displayed in exhibit 2.

3

Here we define foreclosures as foreclosures completed—that is, foreclosure deeds terminating the mortgage and the

owner’s rights to the property.

244

Lambie-Hanson, Herbert, Lew, and Sanchez-Moyano

Refereed Papers

Exhibit 1

House Sales Price Trends in Suffolk County, Massachusetts, and Other Areas, 2000–2012

Source: Authors’ tabulations of data from CoreLogic, Inc. House Price Index

Exhibit 2

Monthly Number of Foreclosures Completed, per 10,000 Homes, in Suffolk County,

Massachusetts, and Other Areas, 2000–2012

Note: Foreclosure completions are counts of foreclosure deeds, regardless of whether properties are sold at foreclosure

auction to a third-party buyer or become real estate owned (REO).

Source: Authors’ tabulations of foreclosure data from Zillow

Foreclosed Property Investors in a Strong Housing Market City:

A Case Study of Boston

245Cityscape

As the urban core of the Boston area, Suffolk County is marked by higher density, older housing

stock. According to 2012 American Community Survey data, 55 percent of units in the county

were built before 1940, while 18 percent of units were built after 1980. Less than 20 percent of the

housing stock is single-family homes. Multifamily structures, split evenly between small multifam-

ily buildings with two to four units and larger buildings, made up most of the stock. In terms of

population demographics, 48 percent of the residents were nonminority, 20 percent were African

American, and another 21 percent were Hispanic or Latino. The median household income in Suf-

folk County was about $51,000, and the poverty rate among individuals was 21 percent.

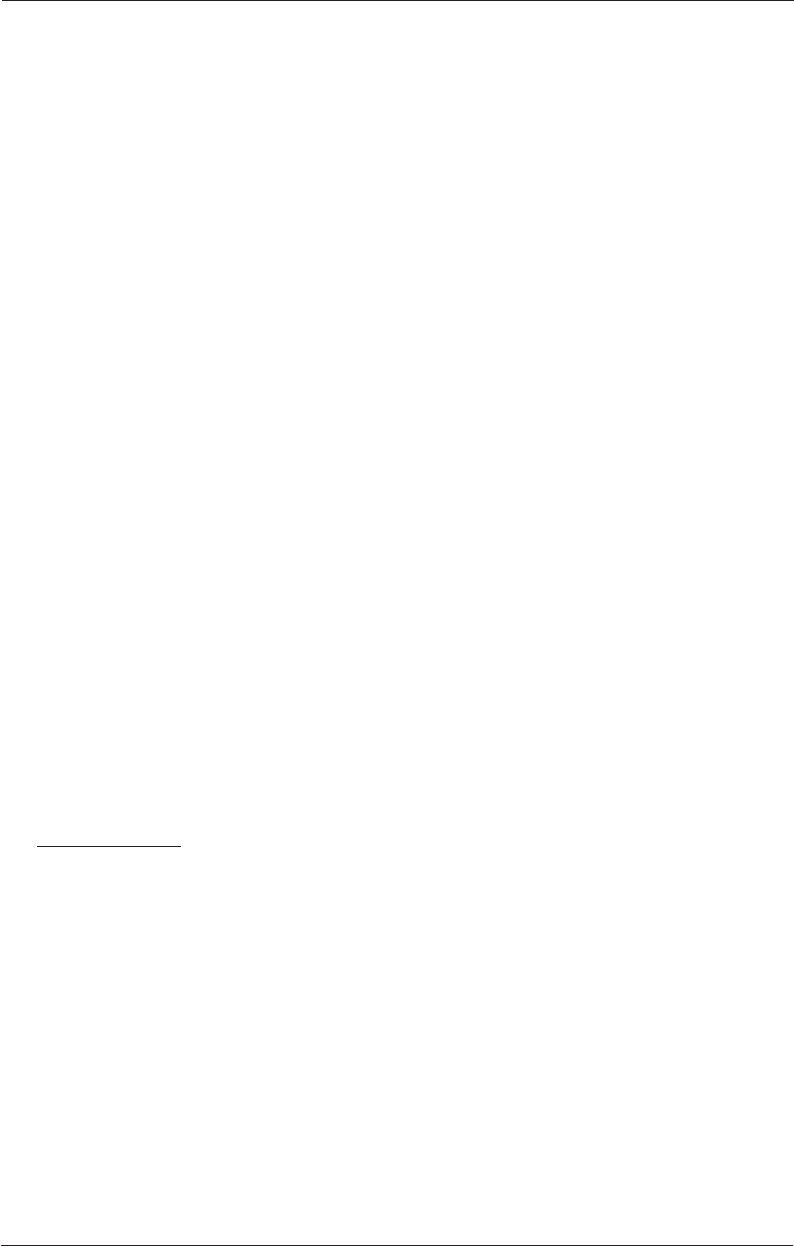

As shown in exhibit 3, following the national trend, homeownership rates in Suffolk County fell

from 40 percent in 2006 and 2007 to 35 percent in 2012. Even at the peak of homeownership,

renters accounted for a clear majority of households. With such a low homeownership rate and a

significant stock of small multifamily buildings, investors have long been active in Boston, but as

evidenced by the falling homeownership rate in recent years, they have increased their presence in

the market.

Exhibit 3

Homeownership Rates for Suffolk County, Massachusetts, and Other Areas, 2005–2012

Source: Authors’ tabulations of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2005–2012 American Community Survey 1-year data

246

Lambie-Hanson, Herbert, Lew, and Sanchez-Moyano

Refereed Papers

Data and Methods

To assess the role that investors have played in acquiring foreclosed properties, we analyze data on

individual transactions involving foreclosure deeds in Suffolk County from a private vendor, the

Warren Group, for the period from 2007 through 2012. The transactions we study include both

properties sold to third parties at the foreclosure auction and those sold by lenders subsequent to

taking title at auction. In this way, we focus on one slice of investor activity, ignoring short sales

and other ways in which investors may purchase properties that were once owned by borrowers in

mortgage distress.

4

We identified investors in two ways: (1) any purchaser whose name was a corporate or legal entity,

rather than an individual’s name, was considered an investor; and (2) any named individual was

considered an investor if he or she purchased more than one foreclosed property in Suffolk County

over the period of study. Linking transactions to the same investor was made difficult by the fact

that investors may use different legal entities to acquire properties, and misspellings may exist

in the database. To account for these discrepancies, we reviewed the buyers’ names in detail and

collected additional information on their addresses and the names of their corporate officers.

5

We

acknowledge that this method understates the level of investor activity to the extent that individu-

als acquire only a single foreclosed property in their own name over the period studied.

This article focuses on 4,700 single-family, two-family, three-family, and condominium properties

that were sold out of foreclosure between 2007 and 2012.

6

Of these foreclosures, 3,830 (81 percent)

were purchased out of REO, while the remaining 870 were purchased directly by third-party buyers

at foreclosure auction and thus never became REO. We identified 320 unique individuals or groups

of investors who purchased two or more foreclosed properties in Suffolk County (exhibit 4).

7

These

buyers purchased a total of 1,947 properties, 41 percent of the sample. Another group of buyers

each purchased only one foreclosed property during our study period but appeared to be corporate

entities, based on a keyword search of the buyer names, including the terms “LLC” (limited liability

company), “Corp.” (corporation), “Inc.” (incorporated), and so on. These owners together bought

4

We unfortunately lack information on short sales in our dataset. Unlike the deeds for foreclosed properties, the deeds for

short sale transactions appear identical to those of arm’s-length transactions (that is, traditional sales in which the price

reflects the market value). As a result, it is not possible to distinguish short sales from arm’s-length sales in real estate

transactions data based on records from local registries of deeds. We also exclude properties surrendered via deeds-in-lieu

of foreclosure, but only a handful of these transactions took place in Suffolk County between 2007 and 2012.

5

Specifically, we used the buyers’ addresses (and in the case of LLCs, the officers), from the Massachusetts Corporate

Database and the Suffolk Registry of Deeds to distinguish between—and link—buyers. On the rare occasions that address

information was missing or ambiguous, we were able to determine if John Doe A and John Doe B were the same person

by looking up their mailing address information in the City of Boston Assessor’s database and comparing their signatures

on documents in the Registry. The owner’s address data unfortunately were not available for the entire county during our

study period and were of insufficient quality across jurisdictions to use mailing addresses as a primary means of identifying

investors.

6

The sample includes foreclosures completed (that is, foreclosure auctions taking place) between 2007 and 2012. This

analysis focuses only on foreclosed properties sold to third-party buyers; in other words, properties still in REO as of the

beginning of 2013 are excluded. It also excludes properties with four or more units that were not condominiums.

7

This total excludes government and nonprofit organizations, which purchased 143 of the properties in the sample (about

3 percent).

Foreclosed Property Investors in a Strong Housing Market City:

A Case Study of Boston

247Cityscape

Exhibit 4

Investors by Number of Foreclosed Properties Purchased

Foreclosed

Properties

Purchased (n)

Investors (n)

Share of

Investors (%)

Total Foreclosed

Properties

Purchased (n)

Share of

Investor-Owned

Properties (%)

1 117 27 117 6

2 147 34 294 14

3 60 14 180 9

4 33 8 132 6

5 to 9 47 11 295 14

10 to 19 15 3 214 10

20 to 49 14 3 418 20

50 or more 4 1 414 20

Total 437 100 2,064 100

Note: Percentages may not add to 100 because of rounding.

Source: Authors’ calculations of data from the Warren Group

117 properties.

8

In total, from 2007 to 2012, 437 unique investors purchased 2,064 properties in

the sample (44 percent). Overall, 60 percent of these investors purchased one or two properties.

Only 1 percent, four investors, purchased 50 or more REOs or foreclosure auction properties.

These purchases, however, amounted to 20 percent of all investor-owned properties. Including

these four largest investors, 33 investors purchased 10 or more properties, totaling one-half of the

investor-purchased properties and 22 percent of all properties sold out of foreclosure in Suffolk

County during this time. We classify those who purchased 10 or more properties as “large investors.”

We have a good deal of information in the Warren Group data about the frequency, timing, and

price points of these purchases. To gain additional information, we interviewed a total of 16

housing market participants in late 2012 and early 2013. Participants were not randomly sampled.

We contacted city agencies and community development corporations (CDCs) active in neighbor-

hoods with high foreclosure rates to request their participation and their suggestions for potential

interview subjects. To a lesser extent, we also used public records information to identify and

reach out to investors. Recruiting investors to participate proved difficult. We ultimately conducted

informal interviews with two small investors, four large investors, three staff members from a city

agency, five staff members employed by local CDCs and other nonprofit organizations, a lender,

and a real estate broker. Although this sample is neither large nor representative, the diversity of

the participants helped us gather information from a variety of perspectives.

8

Individual (noncorporate) buyers who purchased only one foreclosed property and resold it within 1 year accounted for

an additional 157 foreclosed property acquisitions during the study period. Even after a manual inspection of a sample

of these records, it is unclear if the buyers are investors or owner-occupants. In the interest of conservatively measuring

investor activity, we do not treat these buyers as investors.

248

Lambie-Hanson, Herbert, Lew, and Sanchez-Moyano

Refereed Papers

Investors and Their Strategies

Except for the initial years of the housing crisis, 2007 and 2008, investors bought about one-half of the

foreclosed properties sold each year at auction or out of REO (see exhibit 5). The scale of large investor

activity followed a similar pattern. While large investors purchased 9 percent of the foreclosures in

2007 and 14 percent in 2008, they captured more than one-fourth of 2009 through 2012 sales.

Most foreclosed property investors in Boston are locally based. Focusing on only our sample of

33 large investors, more than one-half (18) were based in Suffolk County, 39 percent (13) were

based elsewhere in Massachusetts (typically in the greater Boston area), and 6 percent (2) were

located out of state.

9

Several of the investors had a long history of investing in these neighbor-

hoods, in some cases as long as 20 to 30 years, while others were new to property investment. No

internationally based large investors were in our sample. The smaller investors we studied were

also mostly based in Boston and adjacent communities. The near absence of nonlocal investors in

Boston sets it apart from other cities, such as Atlanta and Cleveland, which have been targeted by

institutional and foreign investors. We suspect that the higher sales prices of foreclosed properties

relative to rents in Boston discouraged outside investment.

Exhibit 5

Share of All Foreclosed Properties Purchased, by Investor Type and Year

Purchase Year Total Purchases (n)

Bought by Investors

(%)

Bought by Large

Investors (%)

2007 290 20 9

2008 1,118 34 14

2009 1,184 50 28

2010 915 50 25

2011 624 48 26

2012 569 49 26

Total 4,700 44 22

Notes: Large investors purchased 10 or more foreclosed properties from 2007 to 2012. “All Foreclosed Properties” includes

properties sold out of real estate owned (REO) status or at foreclosure auction.

Source: Authors’ calculations of data from the Warren Group

Where and What Investors Purchase

Investors bought a greater percentage of foreclosed homes in the neighborhoods (defined here

as census tracts) where the foreclosure rates were highest. These neighborhoods also happen to

have the highest concentrations of minority households. Exhibit 6 shows that neighborhoods

where more than 80 percent of households were minorities experienced foreclosures at a rate of

9

The geographic location of the investors is the assumed place of business, based on records in the Massachusetts Secretary

of State’s online corporate database. When addresses appeared to be those of local agents rather than investors themselves,

we looked for further information, such as addresses in the purchase deeds filed in the local Registry of Deeds. In some

cases, the address appeared to be the investor’s place of residence. In the few instances in which multiple addresses for a

given individual were identified, the most common location was used.

Foreclosed Property Investors in a Strong Housing Market City:

A Case Study of Boston

249Cityscape

Exhibit 6

Neighborhood Characteristics, by Minority Household Share and Household Income Level

Tract Characteristics

Minority Share of Households

> 80% 60–80% 40–60% 20–40% < 20% All

Foreclosure rate (%) 8.7 5.5 3.5 3.4 1.8 4.5

Investors’ share of

foreclosed properties (%)

58 44 36 32 35 46

Large investors’ share of

investor purchases (%)

58 49 48 56 23 52

Homeownership rate (%) 34 38 42 43 54 42

Average house value/unit ($) 154,625 202,155 264,187 239,268 343,442 223,011

Average share of single-

family homes (%)

24 27 31 26 29 27

Average share of two- to

three-family units (%)

56 46 33 33 24 42

Average share of

condominiums (%)

20 27 37 41 46 31

Tract Characteristics

Household Income Relative to Suffolk County

< 80% 80–100% 100–120% > 120% All

Foreclosure rate (%) 7.3 4.9 4.0 1.6 4.5

Investors’ share of

foreclosed properties (%)

52 44 40 37 46

Large investors’ share of

investor purchases (%)

54 53 54 35 52

Homeownership rate (%) 30 39 51 56 42

Average house value/unit ($) 159,631 233,287 218,375 355,404 223,011

Average share of single-

family homes (%)

24 27 31 26 29

Average share of two- to

three-family units (%)

56 46 33 33 24

Average share of

condominiums (%)

20 27 37 41 46

Notes: The reported foreclosure rate includes only properties transferred to a third party and does not include those still held

as real estate owned (REO). “Household Income Relative to Suffolk County” reflects the tract median household income as

a percentage of the Suffolk County median household income. “Large investors’ share of investor purchases” indicates the

percentage of all investor-purchased foreclosed properties that were bought by 1 of the 33 investors who purchased 10 or more

properties in the dataset. Group averages and rates are weighted by number of transactions, properties, or units, as appropriate.

Sources: Authors’ tabulations of data from U.S. Census Bureau’s 2005–2009 American Community Survey 5-year estimates;

authors’ tabulations of data from the Warren Group

8.7 percent, nearly double the countywide rate of 4.5 percent and almost five times the rate in

neighborhoods with a minority household share of less than 20 percent. Tract-level data on the share

of minority households are displayed side-by-side with foreclosure rates in exhibit 7. Chelsea and the

Boston neighborhoods of Roxbury, Dorchester, Mattapan, and East Boston all had high concentra-

tions of minority households, and they also included most of the county’s highest foreclosure tracts.

These neighborhoods overlap heavily with Suffolk County’s lowest income areas. Neighborhoods

with median incomes less than 80 percent of the county median had a foreclosure rate of 7.3 percent,

compared with 1.6 percent for neighborhoods with incomes above 120 percent of the county median.

250

Lambie-Hanson, Herbert, Lew, and Sanchez-Moyano

Refereed Papers

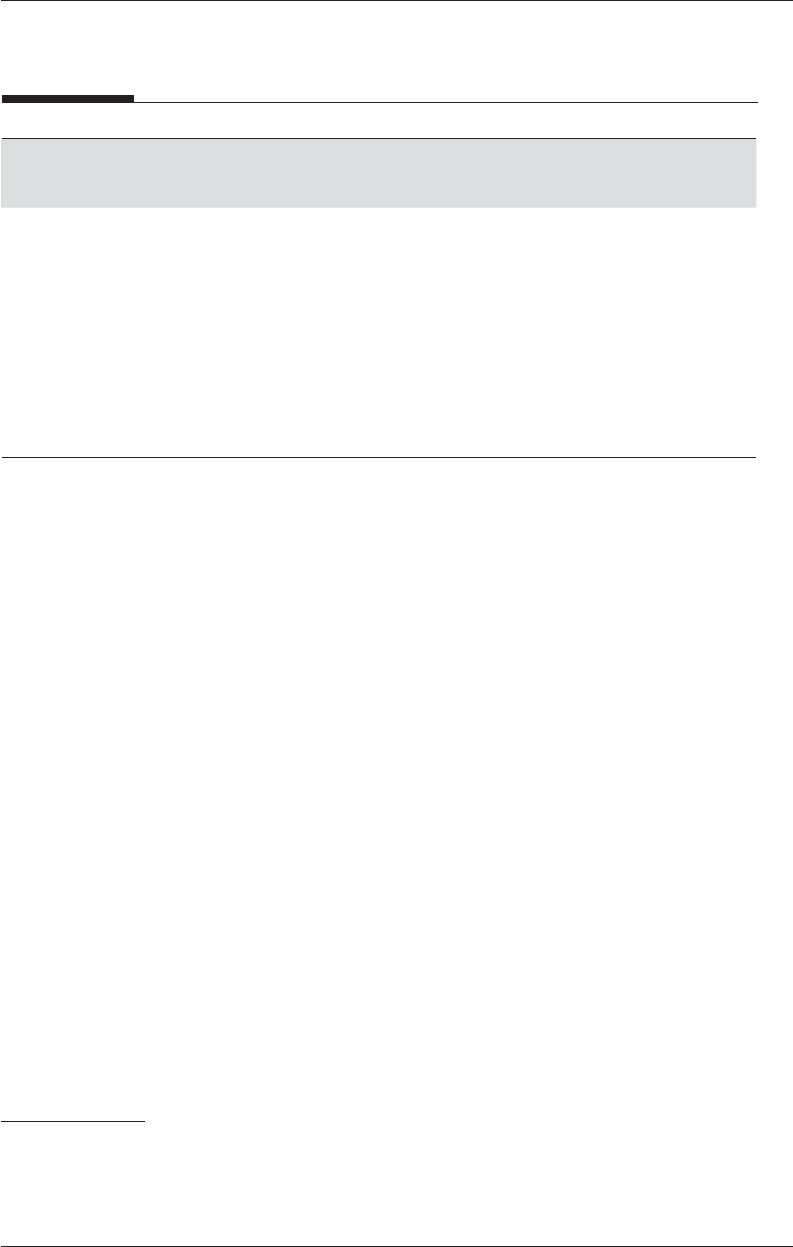

Exhibit 7

Suffolk County, Massachusetts, Neighborhood Characteristics and Investor Prevalence

Share of households non-White

and/or Latino, 2005–2009

Foreclosure RatePercent Minority

Median Price per Square Foot

Investor Share of

Foreclosed Property Purchases

2.0% or less

2.1–5.0%

5.1–10.0%

10.1–15.0%

Over 15.0%

Few properties

67–144

145–250

251–400

401–500

501–787

Few sales

20.0% or less

20.1–35.0%

35.1–50.0%

50.1–65.0%

Over 65.0%

< 5 foreclosures

Foreclosure rate for one- to three-family

and condominium properties, 2007–2012

Median price per square foot

arm’s-length sales, 2007–2012

Percentage of foreclosed properties

sold to investors, 2007–2012

20.0% or less

20.1–40.0%

40.1–60.0%

60.1–80.0%

Over 80.0%

Logan Airport

Chelsea

Revere

East Boston

Winthrop

Boston

Roxbury

Dorchester

Mattapan

Note: Cities are outlined and labeled in bold.

Sources: Authors’ tabulations of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2005–2009 American Community Survey 5-year

estimates; authors’ tabulations of data from the Warren Group

Foreclosed Property Investors in a Strong Housing Market City:

A Case Study of Boston

251Cityscape

Investors purchased 58 percent of foreclosed properties in neighborhoods that had 80 percent or

more minority households and 44 percent in areas with 60- to 80-percent minority households,

compared with about a third in other neighborhoods. Likewise, investors purchased a little more

than one-half of foreclosed properties in the lowest income neighborhoods but only 37 percent in

the highest income areas.

10

Other housing market factors exist in these neighborhoods that may have

influenced investor activity. Homeownership rates are low in Suffolk County’s low-income and majority-

minority neighborhoods. The high share of small multifamily properties, compared with other

structure types, provides an attractive rental market in these neighborhoods and may hinder purchases

by owner-occupants. Average house values per unit (displayed in exhibit 6) and median sales prices

per square foot (displayed in exhibit 7) were also much lower in low-income and high-minority tracts.

Compared with investor activity overall, large investors were notably less active in the highest

income and lowest minority tracts, where property values were highest. The investors we inter-

viewed primarily focused on the lower income neighborhoods of Dorchester, Roxbury, Chelsea,

and Mattapan. One of the investors reported that he perceived himself as a “value investor” who

was not interested in acquiring properties in higher income neighborhoods, arguing that the rents

in these areas could not offset the higher purchase prices.

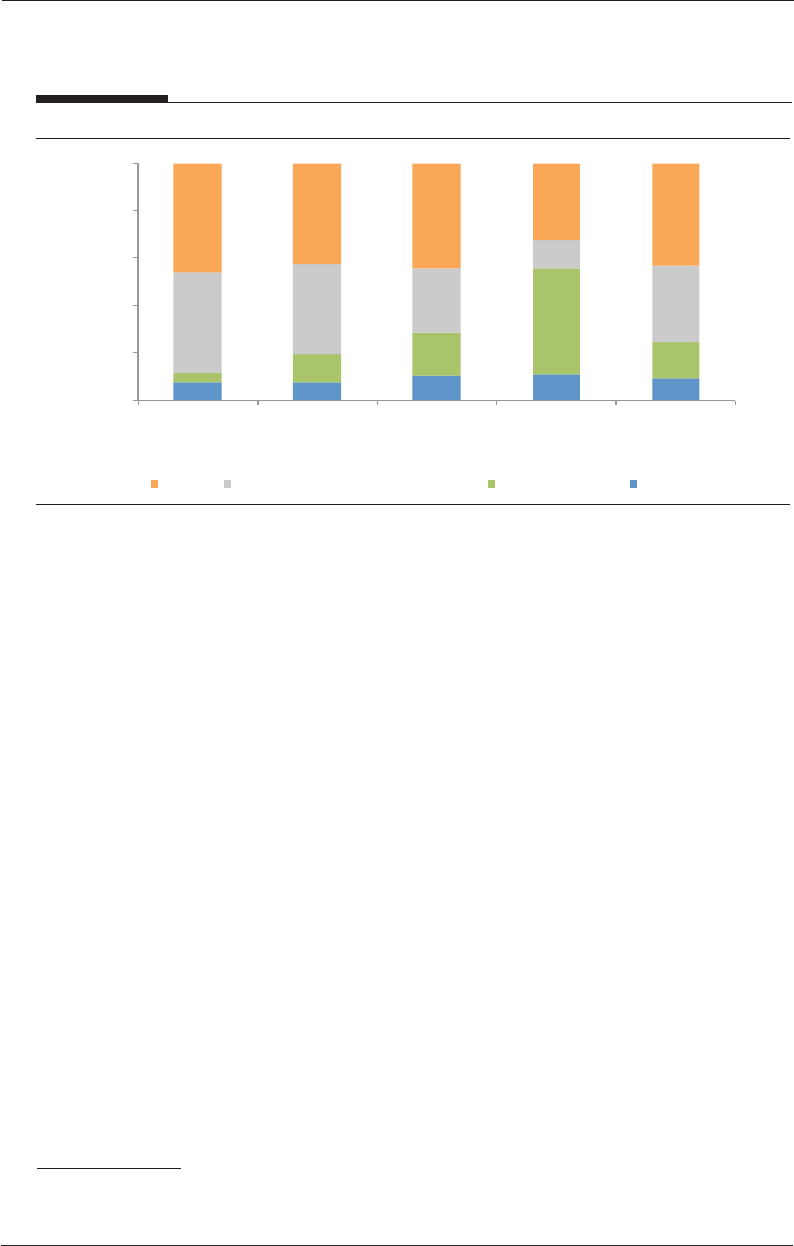

As displayed in exhibit 8, large investors targeted multifamily (two- and three-family) properties

and condominiums. Only 8 percent of purchases by large investors were single-family properties,

in contrast with 17 percent of purchases by small investors and 27 percent of the foreclosed

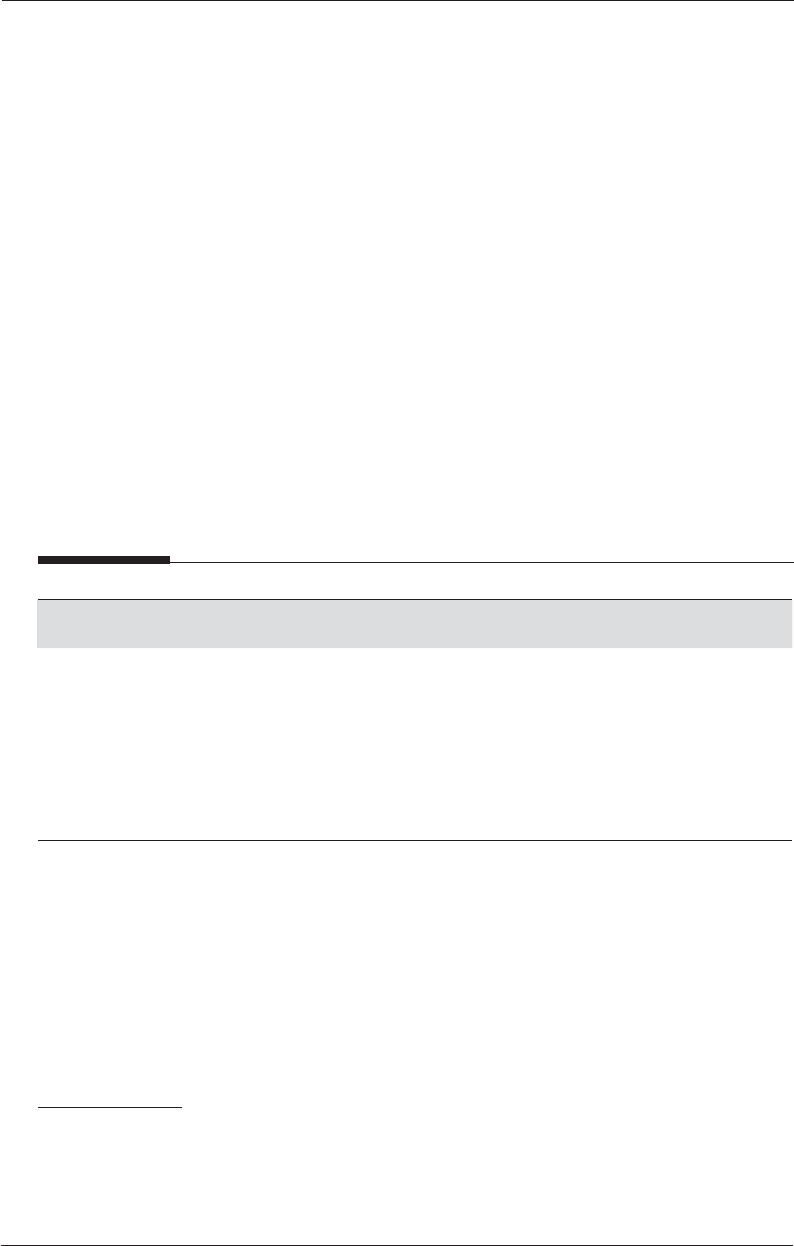

Exhibit 8

Types of Properties Purchased by Purchaser Type

27

29

17

8

20

38

54

44

41

40

35

17

39

51

39

0

20

40

60

80

100

Homeowner Mission-driven

organization

Small investor Large investor All buyers

Percent of foreclosed properties purchased

Purchaser type

Condominium Small multifamily Single-family

Notes: Mission-driven organizations include nonprofit organization and government buyers. Large investors purchased 10 or

more foreclosed properties in the sample. Small investors purchased 1 to 9 foreclosed properties.

Source: Authors’ calculations of data from the Warren Group

10

Note that the total rate of investor activity reported in exhibit 6 (46 percent of foreclosed properties) does not precisely

match the countywide total reported in exhibit 5 (44 percent). This discrepancy is because a small number of tracts are

omitted from the analysis in exhibit 6 because they lacked a sufficient number of transactions to have reliable data on each

field included in the exhibit.

252

Lambie-Hanson, Herbert, Lew, and Sanchez-Moyano

Refereed Papers

properties acquired by owner-occupants. Large investors were particularly likely to purchase

condominiums, which were 51 percent of their purchases. Condominiums made up 39 percent

of small investors’ purchases and 35 percent of the properties bought by owner-occupants. The

remaining 41 percent of purchases by large investors were two- and three-family properties. The

concentration of investment activity in small multifamily and condominium properties can be

explained by the facts that these properties are often better suited for rentals than are single-family

properties and are located in neighborhoods where sales prices have been lower.

The condominium properties in these neighborhoods tend to be part of small multifamily build-

ings, which were formerly wholly owned parcels. Conversions of multifamily properties to condo-

miniums were common in the 1980s and 1990s, with most of the properties having only two or

three units (City of Boston, 2000). Small multifamily property conversions to condominiums were

also in vogue into the mid 2000s, as housing prices peaked (City of Boston, 2005). Conversion

date information is not readily available, which makes it difficult to systematically analyze how

recently foreclosed properties had been converted. We manually traced a number of condominium

foreclosures in our sample, however, using records on file in the Suffolk Registry of Deeds. We found

that many foreclosed condominium properties had been converted from small multifamily rental

properties in the early 2000s. Assuming that the properties were brought up to code and perhaps

renovated at the time of conversion, it is likely that many of the foreclosed condominiums purchased

by investors may have required few or no improvements to make them habitable. Further, unless an

investor acquired all the condominium units in a building, he would not bear the full cost of any ex-

terior improvements. Thus, we would expect condominium units in particular to be attractive to both

prospective owner-occupants and investors. Small multifamily dwellings were the primary focus of

nonprofit organizations, making up more than one-half of their property acquisitions. These proper-

ties offer more opportunities for housing development as they have more units and, according to our

interviews, often required significant improvements to make them marketable for resale or rentals.

Methods of Identifying and Acquiring Foreclosed Properties

During the period we study, the volume of completed foreclosures rose dramatically and then

began to gradually decline as mortgage default rates fell. The investors we interviewed in 2012 and

2013 observed that fewer properties had been coming on the market. One investor attributed this

decline to legislation that took effect in Massachusetts in the preceding few years, which created

a backlog in the number of properties that went through the foreclosure process and affected the

number of foreclosed properties for sale in Suffolk County.

11

At the same time, more investors

entered the market, increasing competition for properties. With fewer foreclosed properties on the

market and increased competition to purchase them, “the foreclosure market is on life support,”

one investor noted. The result, investors told us, was that the price of distressed properties sold

11

Massachusetts extended the foreclosure process in 2008 and 2010 by instituting “right-to-cure” laws that stalled the

foreclosure process by 90 and 150 days, respectively, to provide a “cooling off” period for borrowers and lenders to work

together to achieve mortgage modifications and avoid foreclosure (Gerardi, Lambie-Hanson, and Willen, 2013). Landmark

court cases also influenced the number and timing of foreclosures. U.S. Bank v. Ibañez ruled that lenders must prove that

they hold the mortgages in question before they are able to foreclose. In this sense, the title must be clear at the time

of auction or the sale would be voided. Eaton v. Federal National Mortgage Association ruled that lenders must provide

documentation that they hold both the promissory note and mortgage. These decisions forced some foreclosures to be

repeated and others to be stalled while lenders and servicers worked through the new rules.

Foreclosed Property Investors in a Strong Housing Market City:

A Case Study of Boston

253Cityscape

out of REO in Boston increased significantly during the later years of the foreclosure crisis, making

them less attractive to investors as potential profit margins shrunk. For example, one investor

noted that early in the crisis he bought multifamily properties for $275,000, but by 2012 the same

kind of properties had sales prices that were $100,000 higher.

In our dataset, we see clear evidence of falling sales volumes over time, and some evidence indicates

that REO sales prices increased over time. The data tell an incomplete story, because we cannot

account for property conditions or features beyond neighborhood location and basic property

attributes reported in assessors’ data, namely property size, age, and numbers of bedrooms and

bathrooms.

12

In exhibit 9 we display the simple median REO sales prices and volumes by year and

property type for all of Suffolk County and the two ZIP Codes that experienced the greatest number

of foreclosures. County median sales prices for all property types were at their lowest points in

2009—the year that the overall house price index bottomed out in Suffolk County (see exhibit 1).

The median price for condominiums sold out of REO, for example, was $79,900 that year. In

2012, REO condominiums sold at a median price of $149,900, an increase of nearly 88 percent.

The volume of sales fell by more than one-half between 2009 and 2012.

More appropriate is to examine changes in sales prices within particular neighborhoods. Here we

use ZIP Codes a proxy for neighborhoods. In ZIP Code 02124, which falls in part of the Dorchester

neighborhood of Boston, 519 one- to three-family properties and condominiums were purchased

out of REO between 2007 and 2012. Most of these purchases (60 percent) occurred in 2008 and

2009 alone. For all property types except single-family homes—which as we reported, investors

target less frequently—median prices were at or near their lowest points in 2009. REO prices held

mostly stable in the following years, although medians were higher for small multifamily properties

and condominiums sold in 2012, increasing 10 to 60 percent.

The second greatest number of foreclosed properties bought out of REO (497) was in ZIP Code

02151, covering the city of Revere. In 02151, as in 02124, the median sales price of single-family

REO properties was somewhat lower in 2012 than in 2009, although the median price of REO

condominiums increased 37 percent. Two-family REO property median prices held steady, and

there were relatively few three-family REO properties sold.

Despite the fact that median sales prices were somewhat higher in 2012, particularly for the

property types investors most heavily targeted, investors still purchased about one-half of the

foreclosed properties sold in 2012. The 33 largest investors alone purchased 26 percent of fore-

closed properties. Given the competition for foreclosed properties from nonprofit organizations,

government, and prospective owner-occupants, how did investors capture such a large share?

From our interviews and data analysis, we learned of three main advantages that many investors

possess—particularly large investors. First, investors are often able to purchase properties at fore-

closure auction, before they ever become REO. In contrast, owner-occupants and mission-driven

organizations rarely buy properties at auction. Second, investors appeared well connected and

savvy, having timely knowledge of properties coming on the market as REO. Third, and perhaps

most important, investors have had better access to financing for purchase and rehabilitation.

12

We used a hedonic model to estimate the purchase price for REO properties, controlling for these traits, but the results

simply reaffirmed the patterns in median sales prices discussed in this section. Results are available upon request.

254

Lambie-Hanson, Herbert, Lew, and Sanchez-Moyano

Refereed Papers

Exhibit 9

REO Median Sales Prices and Transaction Volumes, by Year

Year of Sale

Median Sales Price ($) Sales Volume (n)

Single-

Family

Two-

Family

Three-

Family

Condo-

minium

Single-

Family

Two-

Family

Three-

Family

Condo-

minium

Suffolk County, Massachusetts

2007 270,511 308,475 362,625 210,750 82 48 30 62

2008 212,160 235,000 240,000 101,000 200 246 228 353

2009 165,000 195,000 200,000 79,900 179 232 178 403

2010 181,750 200,000 210,000 95,000 142 128 111 285

2011 184,900 203,000 225,000 111,300 101 82 64 227

2012 176,000 208,125 263,000 149,900 105 88 63 179

Percent change

2009–2012

7% 7% 32% 88% – 41% – 62% – 65% – 56%

Dorchester: ZIP Code 02124

2007 310,000 350,000 378,500 122,500 13 9 6 4

2008 207,500 250,000 247,000 65,000 22 29 45 62

2009 150,000 175,900 214,000 70,000 21 31 33 69

2010 153,000 197,625 210,000 75,000 13 11 19 37

2011 150,000 177,500 221,000 86,000 7 12 11 19

2012 145,100 281,000 235,300 105,000 8 8 14 16

Percent change

2009–2012

– 3% 60% 10% 50% – 62% – 74% – 58% – 77%

Revere: ZIP Code 02151

2007 251,250 295,950 527,000 208,000 22 14 1 6

2008 215,000 234,250 225,000 200,000 45 44 21 31

2009 177,500 215,000 200,000 116,000 38 43 7 23

2010 145,450 215,000 231,450 140,000 28 22 6 17

2011 166,000 221,556 240,500 105,500 23 19 2 16

2012 153,000 215,000 251,600 159,000 24 17 4 24

Percent change

2009–2012

– 14% 0% 26% 37% – 37% – 60% – 43% 4%

REO = real estate owned.

Source: Authors’ calculations of data from the Warren Group

Purchases at Foreclosure Auction

Properties sold at foreclosure auction are either bought by third-party buyers (investors or

intended owner-occupants) or become bank owned (REO). During our study period, foreclosure

auctions were well attended in Suffolk County, but they commonly resulted in bank buybacks of

properties: the vast majority (81 percent) of foreclosed properties did not sell to a third party at the

foreclosure auction and thus became REO. These buybacks occur when lenders set their reserva-

tion prices higher than the perceived market value of the properties, so no third-party participants

at the auction are willing to outbid the bank. A greater share of foreclosure auctions resulted in

Foreclosed Property Investors in a Strong Housing Market City:

A Case Study of Boston

255Cityscape

successful sales, however, as the foreclosure crisis unfolded—only about 1 in 10 properties put up

for auction at the beginning of the crisis were sold to third-party buyers, as compared with about

1 in 4 properties in recent years.

13

Buyers at auctions were disproportionately likely to be investors; they bought 75 percent of the

properties sold at auction but only 37 percent of the properties sold out of REO. Investors are often

better equipped to purchase properties at auction, because of the cash deposits required (usually

$5,000 to $10,000) and the risk involved in purchasing foreclosed properties without conducting

inspections. King (2012) makes a similar observation about investors’ advantages buying proper-

ties at foreclosure auctions in Oakland, attributing their success to their ability to pay cash for

properties. Buyers at foreclosure auctions also assume any existing liens on the properties that

take precedence over the mortgage. Large investors were the most likely to purchase properties at

foreclosure auction: 39 percent of all foreclosure purchases by large investors were completed at

auction (rather than out of REO), as opposed to 13 percent of purchases by small investors and

only 8 percent of purchases by other parties, including owner-occupants, government entities, and

nonprofit organizations.

The investors we interviewed told us that they continued to track and attend auctions, but that

over time this strategy had become less effective for identifying and acquiring foreclosed properties.

One investor estimated that after accounting for postponed and cancelled auctions, his chances

of making the highest bid at an auction were only 1 percent. Another reported that as auctions

become scarcer, at almost every auction he would observe five or six of the same bidders who

drove up the sales prices of foreclosed properties by bidding against each other. He added that the

decline in foreclosure auctions and the higher acquisition prices for foreclosed properties repre-

sented a reversal from the height of the foreclosure crisis, when foreclosed properties had lower

sales prices and it was not uncommon for investors attending auctions to buy properties at steep

discounts, particularly in Dorchester: “You had multifamily properties with $700,000 in loans in

Dorchester selling for less than $250,000 at auction.” Other participants told us that although such

deals would sometimes be available, lenders typically set reservation prices close to the unpaid

principal, interest, and fees, making it prohibitively expensive to purchase properties at auction.

Given that only the lender knows its reservation price before the auction, attending auctions can be

fruitless endeavors for investors.

Connections With Real Estate Brokers and Lenders

Large investors tended to be very well connected and were able to leverage their extensive local

networks to find properties to purchase. Our interviews revealed that investors often had relation-

ships with certain brokers who had listed foreclosed properties on behalf of banks and trustees,

and that these relationships enabled them to acquire bank-owned properties quickly, with one

investor noting that “a trusted broker is usually the best way to identify the right properties.”

One nonprofit organization staff member noted that his organization used their connections with

specific investors to help them acquire REO properties, as these investors had ties to real estate

13

As discussed in the following section, the investors we interviewed believed that sales prices at auction, accounting

for property quality, had increased over time. They also reported more competition from other investors at auction.

Considering this information, we presume that the increase in successful auction sales was driven more by investor demand

than a willingness of lenders and trustees to cut their reservation prices.

256

Lambie-Hanson, Herbert, Lew, and Sanchez-Moyano

Refereed Papers

brokers representing foreclosed properties and possessed extensive knowledge of the local housing

market. At least six investors who bought foreclosed properties in Suffolk County were licensed

real estate agents who themselves had sold REO properties on behalf of banks.

Although nonprofit organizations reported benefits from working with some investors, this type

of cooperation appears rare in Boston. City officials and local nonprofit community groups were

familiar with many of the largest investors by name, but only a small handful of these investors had

worked with CDCs and nonprofit organizations to purchase and manage distressed and foreclosed

properties. More often these groups competed to buy properties. Government and nonprofit

organization interviewees noted that they were facing stiff competition from private investors in

acquiring properties, with one interviewee noting that investors seemed to know ahead of time

what properties were coming on the market and were able to act before mission-driven groups

even knew the properties were available.

The First Look Program, rolled out in late 2009 by large mortgage servicers and the government-

sponsored enterprises, was meant to give prospective owner-occupants and mission-driven buyers

priority in REO property acquisitions. One nonprofit organization staff member and one govern-

ment employee we interviewed indicated that the process was cumbersome, and that they had few

successes using it. At least one person remarked that the periods involved—24 to 48 hours for

prospective owner-occupants and mission-driven entities to initially express interest, and about

15 days to make offers—were sometimes too short to have a meaningful effect on their ability to

move forward with a property. One staffer expressed frustration about not having easy access to

information about which properties had become available during the First Look period. Experi-

ences appeared to vary based on the seller, with some, like Fannie Mae, having a more transparent

process and providing more timely information about properties than others.

It was sometimes difficult for nonprofit organizations to compete in the market, especially under

the restrictions of the Neighborhood Stabilization Program (NSP). According to a survey of more

than 90 direct and indirect NSP grantees during the initial years of program implementation, only

a little more than one-half of NSP grantees had purchased one or more properties within the first

5 to 7 months of starting their property acquisition and rehabilitation efforts (Newburger, 2010).

NSP grantees were typically constrained by the types of properties that they could consider and

the amount that they could pay. As the real estate broker we interviewed observed, REO holders

did not appear to be looking to work with many community organizations or nonprofit organiza-

tions, adding that “they are just trying to sell to the highest bidder—there is not much preferential

treatment.” In an effort to offload properties quickly, REO holders may have been more willing to

work with investors. Nonprofit organizations and owner-occupant buyers tended to need mortgage

financing or use programs like the NSP to purchase properties, which added obstacles and delayed

closings (Newburger, 2010). In contrast, investors often paid cash.

Financing

In the wake of the housing bust, lenders became more conservative and wary of providing mort-

gage financing, including to investors. Despite this tightening of lending standards, investors had

access to a variety of funding sources, including their own equity and loans from financial entities

Foreclosed Property Investors in a Strong Housing Market City:

A Case Study of Boston

257Cityscape

other than banks. Some also had established relationships with small community banks. Several of

our interview participants reported that, with fewer financing choices at their disposal, potential

owner-occupants were being outbid by investors who were not as constrained.

We analyze data on the purchases by large investors and break the types of financing down into

four groups: (1) cash (no purchase mortgages associated with a property); (2) hard-money loans

from a firm partially or wholly controlled by one of the foreclosed property investors in our

sample; (3) loans from small commercial banks or thrift banks headquartered in the greater Boston

area; and (4) loans from other types of lenders, including hard-money lenders not associated with

known foreclosed property investors, large commercial banks, mortgage companies, or other

institutions.

14

We find that 43 percent of the purchases by large investors were financed without the use of a

recorded mortgage, which we treated as a cash purchases. Six of the large investors in our sample

of 33 never used mortgage financing to purchase properties. Instead, as we learned through

interviews, they tapped a variety of sources of equity, including their own savings and capital from

institutional investors. In contrast, only 27 percent of properties bought by owner-occupants were

paid for without a mortgage. Smaller scale investors (those purchasing nine or fewer foreclosed

properties) were the most likely to purchase without using a mortgage—nearly 64 percent of their

property acquisitions were cash sales. These smaller investors may have found it more difficult to

access hard-money loans and other sources of capital.

Traditional loans are ill-suited for acquiring foreclosed properties, as the lending process can take

months to complete, undermining deals that need to be completed quickly. Buyers who were able

to purchase a property with cash were reported to have had an advantage over buyers who are

reliant on mortgages, because they were able to speed up the sale and require fewer contingencies

(McKim, 2011). As one interviewee noted, “A lot of [traditional] finance buyers can’t compete with

cash buyers who are willing to pay 10–20 percent above list price; it’s very competitive right now for

a three-family home.” The same person added that the appraisal process could also be problematic

in accessing traditional financing, so the easiest option for purchasing foreclosed properties was cash

financing. As shown in exhibit 10, cash purchases were common even when property sales prices

were high. The use of cash financing declined only when sales prices began to exceed $250,000.

For properties priced above this threshold, cash was still used in 32 percent of purchases.

A little more than one-half of the 33 large investors used some type of mortgage financing in more

than 50 percent of their property acquisitions, and three large investors financed all of their pur-

chases using mortgages. Financing came from a range of sources, commonly “hard-money” loans

to fund property acquisition and rehabilitation. These loans are from nonbank private financial

institutions that specialize in providing real estate backed loans, with mortgage terms ranging from

2 to 24 months. The loans bear relatively high interest rates, averaging 12 to 15 percent, and they

require substantial equity investments, as lenders largely rely on the value of the collateral and not

on the borrower’s ability to pay.

14

For cases in which two or more purchase-money mortgage transactions occurred, we selected the one that appeared to

be the primary lien (represented by a larger balance or, in the case of tied balances, an earlier book and page in the Suffolk

Registry of Deeds) and included it in our analysis.

258

Lambie-Hanson, Herbert, Lew, and Sanchez-Moyano

Refereed Papers

Exhibit 10

Large Investors’ Use of Financing by Property Purchase Price

8

7

10

11

9

4

12

18

44

16

42

38

27

12

32

46

42

45

32

43

0

20

40

60

80

100

Under $75,000 $75,000 to

$124,999

$125,000 to

$249,999

$250,000+ Total

Percent of purchases

Purchase price

Cash Investor-affiliated hard-money lender Small local bank Other lender

Notes: Includes purchases by large investors. Percentages may not add to 100 because of rounding.

Source: Authors’ calculations of data from the Warren Group

Many investors in Boston turn to each other for hard-money loans. Basing our analysis on an in

depth review of the purchase mortgages in our dataset, we find that seven investors operated their

own hard-money lending firms that finance acquisitions for themselves and other investors.

15

One

investor noted that it became common practice in 2008 and 2009, at the peak of the crisis, for

investors to lend to each other because banks were restricting the flow of credit, and investors were

forced to find another source of money. As shown in exhibit 10, hard-money lending was most

common for lower cost properties, particularly those priced at less than $125,000. Only 12 percent

of acquisitions of high-cost properties (priced at more than $250,000) involved hard-money loans

from affiliated investors.

The third most common type of financing in our sample of purchases by large investors, making

up 16 percent of transactions, was loans by small community banks and thrift banks. These

transactions dwarfed the five loans in our sample made by large commercial banks that operate

nationally. The large investors we interviewed reported having established relationships with small

community banks that enabled them to secure a purchase-money mortgage or refinance after re-

habilitating and renting out a property, with one investor noting that “[community] banks tend to

have the best prices and are actively lending. Larger commercial banks have no interest in lending

to investors and they don’t have the local knowledge of the housing market that community banks

do.” As the same investor explained, it is in the interest of a foreclosed property investor to obtain

a bank loan because of the low interest rates; “even for guys who have a lot of their own equity,

I don’t know a single person who doesn’t take a loan [from a traditional lender]. Borrowing is so

cheap that I can still make money and achieve a 10 percent cap rate. I make 5 percent on every

15

We classified lenders based on information we gained from their websites and other online sources about product

offerings, length of loan terms, and underwriting practices.

Foreclosed Property Investors in a Strong Housing Market City:

A Case Study of Boston

259Cityscape

nickel I borrow, so leverage is working in my favor.” Community banks appeared to be particularly

active in financing the purchase of higher cost properties. Loans from community banks financed

the purchase of 44 percent of the properties bought by large investors for more than $250,000.

The type of financing used at purchase does not tell the whole story, though. Through our inter-

views, we identified a common two-step financing model: taking out a short-term, high-cost loan

or using their own equity to finance the initial purchase and rehabilitation of a property, and then

after the property is rented and producing a stable income stream, refinancing through a traditional

lender. We confirmed this behavior in our dataset. After using a mortgage from a hard-money

lender to purchase a foreclosed property, 56 percent of investors took out a subsequent mortgage

on the same property, presumably a refinance loan, at a later date.

16

In contrast, 39 percent of

buyers purchasing with cash later took out a mortgage, and 42 percent of those initially using

loans from small local banks appeared to refinance. Only 29 percent of investors using other types

of financing were observed to take out another mortgage after the purchase date. These investors

initially borrowed from large banks, mortgage companies, and hard-money lenders not affiliated

with known Suffolk County foreclosed property investors.

One investor explained that his strategy of initially using hard-money loans and later refinancing

through a bank proved effective because banks were more likely to assist with financing a fore-

closed property if they saw that the property had been rehabilitated and leased for a certain period

of time with positive cash flow. In his words, “once you fix it up and rent it out, the property is

worth more than what you bought it, in the bank’s eyes, because it’s generating income. The bank

will run the cap rate and see that after the rehab, the property is now worth $450,000 instead

of $250,000, bringing in $3,000 per month in positive cash flow. Then the bank will allow you

to refinance 75 percent of the value.” Another investor added that his ability to refinance with a

traditional lender after purchasing a foreclosed property affected his decision to resell or hold the

property; if he was able to secure refinancing, he would certainly continue to hold it.

From our interviews we learned that owner-occupants and small-scale investor landlords struggled

to compete with large investors in Boston because large investors had greater access to cash, hard-

money loans, and alternative lending streams. Financing was a particularly salient issue for those

wanting to buy properties that would require substantial spending on rehabilitation. One nonprofit

organization staff member who worked with small property owners observed that “the big issue is

that usually you can’t get more money in your loan for making improvements.” According to the

same person, although small property owners previously had the ability to take out a bank loan

for improvements, limited credit availability for this purpose had made it more difficult to borrow

for rehabilitation expenses. Another nonprofit organization staff member observed that “small

investor-owners tend to operate from check to check to make repairs.” He had seen cases of small

investor-owners who were foreclosed on because they wound up overpaying for a property in poor

condition, initially intending to accumulate rental income but ultimately finding themselves unable

to keep up with the necessary repairs and maintenance.

16

Our data do not enable us to distinguish between refinance mortgages and subordinate-lien mortgages taken out after the

time of purchase.

260

Lambie-Hanson, Herbert, Lew, and Sanchez-Moyano

Refereed Papers

Postpurchase Property Management

As we have established, investors accounted for a large share of foreclosed property acquisitions in

Suffolk County. We now turn to the question of what these investors did with the properties they

bought. We find that investors in Boston and neighboring communities tended to hold proper-

ties, although some resold or even flipped them. Holding properties in Boston appears to have

been desirable because of the strong rental market in the area, especially renting units to voucher

holders. Positive expectations about rents and future house prices led some investors to spend

substantial sums rehabilitating properties.

Strategies With Respect to Holding or Selling Properties and the Challenges of

Rental Management

Mallach (2010a) presents a typology of distressed property investors that distinguishes between

several common types of business strategies. His typology includes four categories: rehabbers,

flippers, milkers, and holders. Although rehabbers and flippers purchase distressed properties

with the goal of reselling them to buyers, the main difference between the two categories is that

rehabbers are more focused on investing in necessary capital improvements and renovations for the

property, while flippers typically put minimal investment into the property before selling quickly

to other buyers. Meanwhile, milkers and holders purchase properties with the intention of renting

them out. Unlike holders, however, milkers do not invest in property maintenance and tenant

selection practices because they are focused on the cash flow that can be generated from the spread

between rents and the low property acquisition and maintenance costs. Holders are generally more

cognizant of property appreciation and dedicate more financial resources to property maintenance

and tenant screening.

In practice, almost all of the large foreclosed property investors in Boston had both held and resold

properties, rather than pursuing a single strategy. The predominant strategy was to hold, however,

at least until the housing market improved. Overall, 68 percent of properties were held for at least

2 years, and 53 percent were still owned by the same large investor as of January 2015. Looking at

the 33 large investors individually, 21 (64 percent) held at least two-thirds of their properties for

2 years or longer. Of these 21 investors, 12 still held two-thirds of their properties by January 2015.

Despite the prevalence of a holding strategy among investors, 8 large investors resold at least one-

half of their properties within 2 years of purchase. These investors could be classified as flippers

or rehabbers, according to Mallach’s typology. For the most part, though, flipping in Boston seems

to have been rare; for the properties resold, the median time to resale was about 9 months, which

suggests that at least some improvements could be made to the properties before they were resold.

Only one large investor had a median holding time of less than 30 days, while another two had

median times until resale of less than 90 days. Only 117 properties resold by large investors (7 per-

cent) were resold in less than 90 days.

Based solely on purchase and resale prices (ignoring other factors, like costs of building improve-

ments or financing), 97 percent of resold properties by large investors resulted in gross gains (that is,

sales price exceeding purchase price). The median dollar gain was $96,000; the median percentage

Foreclosed Property Investors in a Strong Housing Market City:

A Case Study of Boston

261Cityscape

gain was 63 percent. As a point of comparison, the median gross return on a nonforeclosed

property purchased and sold in Suffolk County during this period was 12 percent.

17

Foreclosed

property investors earned these high returns despite the fact that most of their portfolios were

concentrated in low-income areas with high foreclosure rates.

Most sales by large investors conducted through 2012 were to owner-occupants, with only 39

percent of properties sold to other investors. The prevalence of sales to owner-occupants or other

parties varied greatly, however, based on the investor’s primary business strategy. Most of the

investors who had resold the bulk of their properties primarily targeted owner-occupants, and even

when they sold to other investors, they typically did not sell to another large investor. On the other

hand, among investors who primarily held their properties, it was less common to sell to owner-

occupants; they instead generally sold to other investors, often to large investors.

18

The dominant strategy of holding properties in Suffolk County appears to have been driven by

high rental demand, although house price recovery served as an incentive to resell. One investor

explained that he preferred to resell multifamily properties after acquiring and renovating them,

rather than holding properties for rental income. “Multifamily market values are such that it

makes sense to flip the properties,” he said. “We usually extensively renovate our properties so the

condition they are in when we purchase them is irrelevant. They will sell for a premium given our

renovations.” To estimate the feasibility of a resale versus a holding strategy for each individual

small multifamily property, he would determine whether he and his partner were able to achieve a

per-property profit of $50,000. If not, he would hold onto these properties for the rental income;

he estimated that he wound up holding around 25 percent of the inventory that he purchased at

auction. Over time, Boston and other cities may see a larger share of investors reselling their prop-

erties. Two investors commented that they and their partners initially held and rented out nearly all

their purchases, but as sales prices were increasing in the area, they planned to divest.

Similar to Immergluck and Law’s (2014) findings on Atlanta, we learned that many investors in

Boston who rented out their properties had a preference for tenants with Housing Choice Vouch-

ers. Voucher holders were attractive as tenants because they represented a reliable stream of rental

income in neighborhoods where lower income households may be stretched to afford market-rate

rents. As one investor put it, voucher tenants represented “guaranteed money,” as the federal

government pays the difference between the tenant contribution and the fair-market rent. Voucher

holders were also more likely to seek housing in distressed neighborhoods because of the lack of

affordable housing throughout Boston. Several investors noted that within these neighborhoods,

fierce competition among landlords over leasing to voucher holders provided incentives for inves-

tors to rehabilitate distressed properties and to use more expensive finishes, because nicer units

tend to rent out faster.

Not all investors were competing for voucher tenants, however. Interview participants noted that

very few “mom and pop” investors were adept at handling vouchers, because of strict requirements

and high housing standards mandated by the program. Larger, “professional” landlords had more

17

As an anonymous referee pointed out, investors who are renting out their properties may delay sales until they receive a higher

asking price. By contrast, traditional sellers may feel a greater urgency to sell, which could lead them to accept lower offers.

18

For a more detailed description of these patterns, see Herbert et al. (2013).

262

Lambie-Hanson, Herbert, Lew, and Sanchez-Moyano

Refereed Papers

capacity to manage the requirements for the voucher program, particularly those with property

management companies. The volatility of the market and recent policy changes also presented

broader challenges in rental and property management, particularly for less sophisticated, smaller

investors. For example, increased legal protections provided to tenants living in foreclosed homes

have affected purchase and property management strategies. In 2010, Massachusetts enacted a law

that prohibited banks from evicting tenants living in foreclosed properties.

19

Managing rents and

existing tenants in previously foreclosed buildings that are still occupied can present challenges