Qualitative Health Research

2017, Vol. 27(7) 1060 –1068

© The Author(s) 2016

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1049732316649160

journals.sagepub.com/home/qhr

Methods

Direct observation has been described as the gold standard

among qualitative data collection techniques (Murphy &

Dingwall, 2007). Observing people in their natural environ-

ment not only avoids problems inherent in self-reported

accounts (Mays & Pope, 1995), but can also reveal insights

not accessible from other data collection methods, such as

structures, processes, and behaviors the interviewed partici-

pants may well be unaware of themselves (Furlong, 2010).

Yet, despite now well-documented advantages of observa-

tion over other forms of qualitative data collection, to date,

observation methods have been underused (Mulhall, 2003;

Walshe, Ewing, & Griffiths, 2012), and interviews remain

the most common form of qualitative inquiry in health care

research settings (Morse, 2003; Phillips, Dwan, Hepworth,

Pearce, & Hall, 2014; Russell et al., 2012). Undertaking

observation, particularly in-depth forms of observation

such as traditional ethnography (Savage, 2000), is often

time-consuming, costly, and practically challenging in

health care settings (Curry, Nembhard, & Bradley, 2009;

Morse, 2003; Savage, 2000; Walshe et al., 2012).

More pragmatic contemporary approaches to observa-

tional research suitable for health settings combine less

intensive observation data collection methods with other

forms of data collection in a case study or other type of

multiple-method design (Hjalmarson, Ahgren, &

Kjölsrud, 2013; Kislov, Walshe, & Harvey, 2012).

Incorporating multiple qualitative methods generates the

opportunity for more complete explanations. However,

the unique value of observation methods in multiple-

methods research has remained largely unexplored. All

too often, such studies are in fact predominantly inter-

view driven, failing to use observation data to their full

potential or not reporting them distinctively (Morgan,

Pullon, & McKinlay, 2015; O’Cathain, Murphy, &

Nicholl, 2008).

The focus of this article is on an observationally driven

approach to case study research the authors adopted

649160QHR

XXX10.1177/1049732316649160Qualitative Health ResearchMorgan et al.

research-article2016

1

University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand

Corresponding Author:

Sonya J. Morgan, Department of Primary Health Care and General

Practice, University of Otago, Wellington, P.O. Box 7343, Wellington

6242, New Zealand.

Email: [email protected]

Case Study Observational Research: A

Framework for Conducting Case Study

Research Where Observation Data Are

the Focus

Sonya J. Morgan

1

, Susan R. H. Pullon

1

, Lindsay M. Macdonald

1

,

Eileen M. McKinlay

1

, and Ben V. Gray

1

Abstract

Case study research is a comprehensive method that incorporates multiple sources of data to provide detailed

accounts of complex research phenomena in real-life contexts. However, current models of case study research

do not particularly distinguish the unique contribution observation data can make. Observation methods have the

potential to reach beyond other methods that rely largely or solely on self-report. This article describes the distinctive

characteristics of case study observational research, a modified form of Yin’s 2014 model of case study research the

authors used in a study exploring interprofessional collaboration in primary care. In this approach, observation data

are positioned as the central component of the research design. Case study observational research offers a promising

approach for researchers in a wide range of health care settings seeking more complete understandings of complex

topics, where contextual influences are of primary concern. Future research is needed to refine and evaluate the

approach.

Keywords

appreciative inquiry; case studies; case study observational research; health care; interprofessional collaboration;

naturalistic inquiry; New Zealand; observation; primary health care; research design; qualitative

Morgan et al. 1061

during the Study of Interprofessional Practice in Primary

Care (SIPP Study)—a multiple case study designed to

explore interprofessional collaboration (IPC) in primary

care teams in New Zealand. We have coined the term

case study observational research (CSOR) to denote this

as a distinct form of case study research (CSR). The

approach incorporates both non-participant observation

of practice activity and policy documents and the non-

observation method of interviewing. However, CSOR

gives priority and precedence to the collection and analy-

sis of observation data, to better understand complex phe-

nomena, such as IPC.

CSR examines “a contemporary phenomenon in depth

and in its real-world context” (Yin, 2014, p. 237). Multiple

methods are used to collect data for each “case” or sub-

ject of study, which is not the same as mixed-method

research (Morse & Cheek, 2014; Yin, 2014). As a method,

CSOR is specific to CSR design. To place our CSOR

approach in its methodological context, we first provide

an overview of the two key antecedents to the approach:

CSR and observation methods. Second, we describe the

informing philosophical approach and the research set-

ting in which CSOR was developed and finally define the

three distinctive features of the approach.

Overview: Case Study Research and

Observation Method

CSR is a comprehensive method increasingly applied in

health sciences research (Anthony & Jack, 2009; Boblin,

Ireland, Kirkpatrick, & Robertson, 2013; Carolan, Forbat,

& Smith, 2016) to investigate “how” or “why” qualitative

research questions, “when the investigator has little con-

trol over events and when the focus is on a contemporary

phenomenon within some real-life context” (Yin, 1994,

p. 1). In this way, CSR differs from other research meth-

ods, such as experiments, which purposefully separate a

phenomenon from its context. In CSR context is inextri-

cably linked to the phenomena under investigation and,

therefore, is crucial to understanding real-world cases

(Yin, 2014).

Several models of CSR exist, each emphasizing differ-

ent philosophical positions (Abma & Stake, 2014).

Within the health care arena, Yin’s (1994) model is com-

monly described and used. Case studies can include either

single- or multiple-case designs. Depending on the con-

text, multiple cases can provide greater confidence in

findings generated from the overall study (Yin, 2014). A

characteristic feature of CSR, the collection of data using

multiple sources for each case (Carolan et al., 2016),

allows triangulation of evidence. Triangulation improves

the accuracy and completeness of the case study, strength-

ening the credibility of the research findings (Cronin,

2014; Yin, 2014). Sources of data collected vary

depending on the research question. Commonly used

methods include interviews, observation of archival

records, and direct observation of study participants (Yin,

1994).

Either as part of CSR or as a stand-alone method,

observation methods involve directly observing and

recording how research participants behave within and

relate to their physical and social environment as it

unfolds (Mays & Pope, 1995; Mulhall, 2003). Observation

provides “insight into interactions between dyads and

groups; illustrates the whole picture; captures context/

process; and informs about the influence of the physical

environment” (Mulhall, 2003, p. 307). Approaches to

observation vary according to the philosophical orienta-

tion of the research and the role researchers adopt along

the continuum of observer to participant (Walshe et al.,

2012). Observation methods may consist of non-partici-

pant observation, where the researcher has no other rela-

tionship with the group being observed (including

shadowing; Quinlan, 2008) through to participant obser-

vation, where the researcher is also a member of the

group being observed (Bloomer, Cross, Endacott,

O’Connor, & Moss, 2012). Recording methods range

from structured template recording to unstructured field

noting (Walshe et al., 2012). More recently, video-record-

ing techniques have proved a valuable way to capture

observations (Carroll, Iedema, & Kerridge, 2008; Collier,

Phillips, & Iedema, 2015; Cronin, 2014; Forsyth, Carroll,

& Reitano, 2009; Iedema et al., 2009).

Compared with observation methods, non-observation

(self-report) qualitative methods, such as interviews or

focus groups, are typically less challenging to undertake

but are subject to participant reporting problems (Curry

et al., 2009; Morse, 2003; Walshe et al., 2012; see Table 1

for summarized strengths and challenges of observation

vs. self-report methods). Thus, observation methods

stand in a class of their own. Observation allows the

researcher to actually see what people do rather than what

they say they do (Caldwell & Atwal, 2005; Mulhall,

2003; Walshe et al., 2012). Systematically observing peo-

ple in naturally occurring contexts can reveal much more

information than individuals may recall, be aware of,

choose to report, or decide is relevant than with other

self-report data collection methods (Mays & Pope, 1995;

Morse, 2003; Mulhall, 2003).

In a health care context, observation methods enable

the exploration of elements of health care that are not

possible by relying on self-report methods (Oandasan

et al., 2009; Russell et al., 2012), providing insights into

the complexity of clinical practice (Dowell, Macdonald,

Stubbe, Plumridge, & Dew, 2007; Lingard, Reznick,

Espin, Regehr, & De Vito, 2002). For instance, observa-

tion methods have been used to observe various aspects

of the interaction between professionals and patients

1062 Qualitative Health Research 27(7)

during medical consultations (Dowell et al., 2007;

Morgan, 2013). They have also been found to be particu-

larly useful for research involving vulnerable patients

where the least intrusion or stress on participants is

desired (Bloomer et al., 2012; Bloomer, Doman, &

Endacott, 2013; Walshe et al., 2012).

Some well-conducted studies have used observation

methods to examine professional practice and communi-

cation between health professionals such as team func-

tioning/communication in the operating room (Lingard

et al., 2004), ward rounds (Carroll et al., 2008), rehabili-

tation settings (Sinclair, Lingard, & Mohabeer, 2009),

and primary care settings (Oandasan et al., 2009; Russell

et al., 2012). Nonetheless, in many health care research

studies incorporating both observation and other forms of

data collection, the observation data are only mentioned

in passing and are therefore underexploited, often taking

a “back seat” to interview data (Morgan et al., 2015).

Thus, for the study next described, an approach to con-

ducting CSR was required that would combine the

strengths of different methods but specifically prioritize

the observation data.

Development of the CSOR

Framework: The SIPP Study

The SIPP Study conducted in 2012–2014 explored feasi-

ble methods of investigating elements of IPC in primary

care practice (Pullon, Morgan, Macdonald, McKinlay, &

Gray, 2016). CSR (Yin, 2014) was originally selected as

an appropriate method, using a multiple case study

design. IPC is challenging to investigate, and the essen-

tial elements of effective IPC remain obscure (Morgan

et al., 2015). IPC has been described as “an active and

ongoing partnership, often between people from diverse

backgrounds, who work together to solve problems or

provide services” (Barr et al., 2005, as cited in Ødegard,

2006, p. 2). It has been shown to improve patient satisfac-

tion (Proudfoot et al., 2007) and health outcomes (Strasser

et al., 2008), yet IPC is far from integral to everyday

practice (Xyrichis & Lowton, 2008).

At the outset, the research approach drew on both nat-

uralistic inquiry (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) and apprecia-

tive inquiry (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987). Naturalistic

inquiry contends that “realities are wholes that cannot be

understood in isolation from their contexts” (Lincoln &

Guba, 1985, p. 39). Consistent with the interpretivist tra-

dition of naturalistic inquiry (Lincoln & Guba, 1985), the

aim of the research was to explore the observed nature of

collaboration between practice team members in context

from multiple perspectives. Appreciative inquiry exam-

ines what works well in an organization and acknowl-

edges but does not focus on problems (Cooperrider &

Srivastva, 1987). Informed by the principles of this

approach, we sought to identify key elements influencing

effective IPC. A secondary aim was to investigate whether

well-established interprofessional competencies devel-

oped in Canada (Canadian Interprofessional Health

Collaborative [CIHC], 2010) were evident in the every-

day practice of primary care teams in a New Zealand con-

text. To extend beyond elements of personal

interprofessional relationships and intrinsic team factors

that have been well captured by numerous interview-

based studies, observation methods were incorporated

from the outset in the design of the research. However, as

conventional case study models, such as Yin (2014), do

not distinguish observation data from other types of data

collection in terms of their unique significance and poten-

tial, we modified Yin’s CSR method. This observation-

ally driven, sequential approach to CSR explicitly

positions the observation data as the central component

of the research design, where observation data are both

collected and analyzed prior to augmenting by other non-

observation methods.

Table 1. Observation Versus Self-Report Data Collection Methods: Strengths and Challenges.

Observation Methods Self-Report Methods

Strengths Challenges Strengths Challenges

Allows direct examination of

behavior/activity in real time

Provides information about

topics participants may

be unwilling to talk about,

unaware of, or unable to recall

Undertaken in naturally

occurring contexts—allows

examination of contextual

factors

Time-consuming, expensive, and

ethically challenging in some

settings

Hawthorne effect—participants

may change their behavior

when they know they are

being observed

a

Field noted/video-recorded

observations are influenced by

what the observer chooses to

record/analyze

Allows participants to describe

their own perceptions and

views about the topic of

interest

Relatively straightforward to

undertake

Relies on the information

participants are willing to talk

about, aware of, or able to

recall

Interview/focus group content is

influenced by the perspective

of the interviewer/other

participants

Does not capture context

a

Landsberger (1958).

Morgan et al. 1063

Study Participants and Data Collection

Three widely diverse general practices in a New Zealand

region were approached to participate in the study and all

agreed to take part, constituting the “cases” included in

the study. The practices were purposively selected on the

premise that they were already successfully engaged in

some interprofessional activity, increasing the potential

learnings from the cases (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987;

Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Practices varied with respect to

geographical location, size of enrolled patient population,

business model, ownership/governance, and workforce

composition. Data collection at each practice included

non-participant unstructured observation (Mays & Pope,

1995) of informal practice activity (field notes), meetings

(video-recorded), and policy document review (field

notes). Observation-informed individual semi-structured

interviews (audio-recorded) were undertaken only after

other observation data collection was complete. Consent

to participate in the study and have informal practice

activity observed was obtained from the practice as a

whole following presentation of the proposed study by

the research team at a practice meeting. Staff then indi-

vidually consented to the video-recorded meetings and

interviews (Pullon et al., 2016).

Direct observation of informal staff interactions at

each practice were made by a research nurse with a pro-

fessional background who was both familiar with the rou-

tines and sensitivities of the clinical environment and had

extensive experience collecting naturalistic observation

data in primary care settings. The research nurse had no

prior relationship with the selected practices. Her role and

the purpose of the observations, including the apprecia-

tive nature of the research, were explained to participants

during the initial meeting with the study team. Because

we sought to examine how participants naturally inter-

acted with each other, the research nurse situated herself

unobtrusively in the practice and had limited interaction

with participants. Observations were undertaken in as

many of the “common” areas of the practice as possible,

excluding consulting rooms. They were also undertaken

at different times of the day and week. Consultations with

patients were not observed. Observations recorded were

governed by the research nurse’s interaction with and

growing knowledge of the context. They were not guided

by predefined tools or templates (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Observations were recorded initially as handwritten

detailed verbatim field notes with time markers. These

notes were supplemented with post-observation summa-

ries generated immediately following the observation

period and incorporated the research nurse’s reflections

on her own feelings, actions, and responses to the situa-

tions observed (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Mays & Pope,

1995). These field notes and reflective summaries were

promptly circulated to the research team for review, who

in turn added comments and observations, which were

circulated to all members.

Following observations of informal staff interactions,

practices chose which regular practice meeting would be

video-recorded by the research nurse on two successive

occasions. Different types of meetings were chosen at

each practice (i.e., a small team of three to five members;

a medium sized team of six to 14 members, and a large

team of 15+ members) and included different discipline

mixes. Assurance was given as to secure encrypted stor-

age of video and other data. The research team met regu-

larly to review and discuss the video-recorded meetings,

and selected sequences were transcribed verbatim.

Practice documents (e.g., policies, terms of reference,

floor plans) were viewed and summarized as separate

field notes. Finally, observation-informed interviews

were undertaken with a range of practice staff and tran-

scribed verbatim. Ethical approval was granted by the

University of Otago Health Ethics Committee, CEN/11/

EXP/038.

Data consisted of a total of 32 hours of field-noted

observation of informal practice activity, 6 hours of

video-recorded team meetings, 17 individual interviews

(duration ranging from 24 to 48 minutes), and 43

reviewed documents. To support the process of analysis,

all of these separate items of data, including videos,

were imported into the software program NVivo 9

(Bazeley & Jackson, 2013). Preliminary case-specific

findings were presented back to each participating prac-

tice, and the ensuing discussion further informed and

strengthened the credibility of study findings (Boblin

et al., 2013; Houghton, Casey, Shaw, & Murphy, 2013).

Study results have been reported elsewhere (Pullon

et al., 2016).

The remainder of this article focuses on the three fea-

tures of the CSOR approach that differentiate it from con-

ventional CSR: (a) Observation data are collected prior to

and inform the subsequent collection of non-observation

data, (b) observation data determine the analytic frame-

work, and (c) observation data are explicitly referenced in

the final results. Examples from the SIPP Study are used

to illustrate how following this framework afforded pre-

cedence to the observation data.

Distinctive Features of the CSOR

Framework

The three key characteristics of CSOR differentiate it

from conventional CSR and allow the observation data

to contribute uniquely to the case study findings. The

first difference between traditional CSR and CSOR

emerges when it comes to collecting the case study

evidence.

1064 Qualitative Health Research 27(7)

Observation Data Collected Prior to (and

Inform) the Subsequent Collection of Non-

Observation Data

The collection of multiple sources of evidence is central

to CSR (Yin, 2014). However, advocates such as Yin do

not place any significance or importance on the order in

which different sources of data are collected, and indi-

vidual case studies appear to comprise independent data

sets (e.g., interviews, observations, documents, and sur-

veys) collected in no particular sequence.

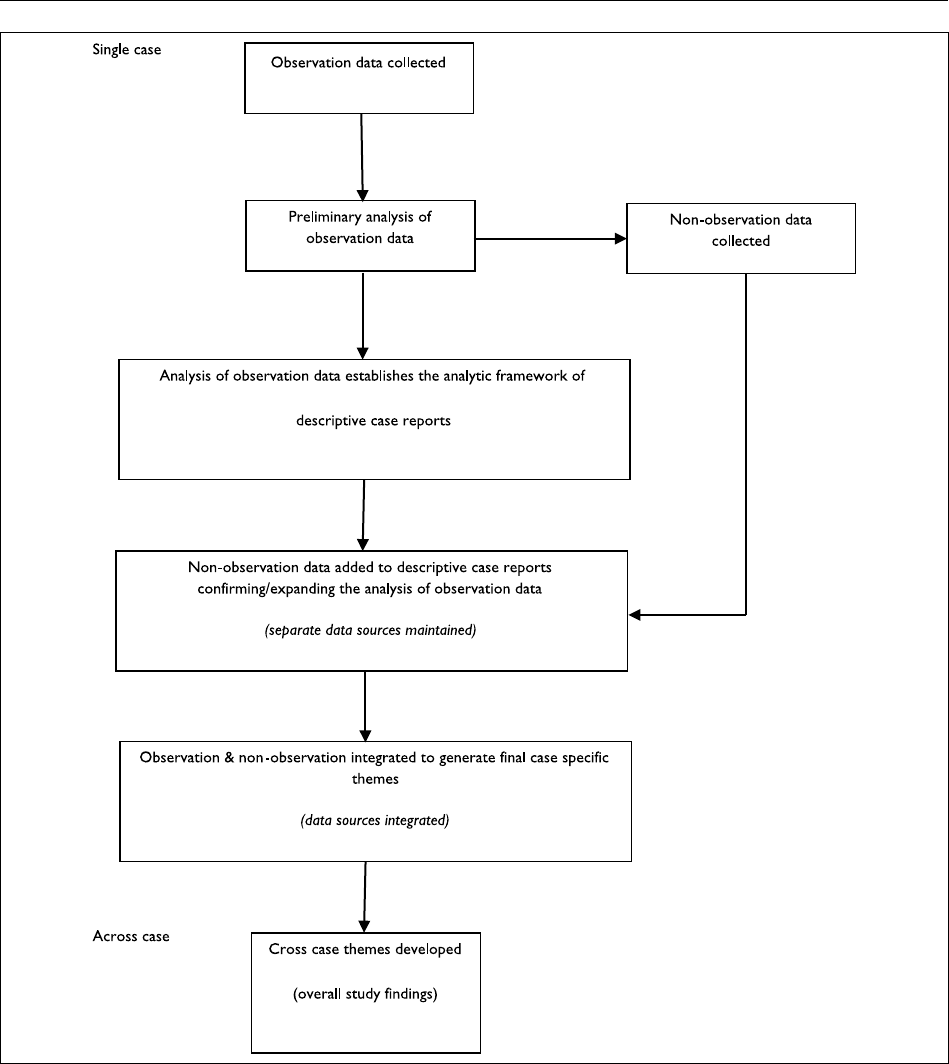

In contrast to conventional CSR, within the CSOR

framework, observation data are analyzed ahead of the

subsequent collection of non-observation data. In this

way, the collection of non-observation data is informed

by the observation data and allows corroboration and fur-

ther exploration of significant observations (Figure 1).

For instance, in the SIPP Study, collecting observations

of health professional interactions prior to undertaking

individual interviews allowed us to consider actual exam-

ples of notable practice team decisions, to explore and

confirm with participants during interviews.

Observation Data Determine the Analytic

Framework

The analysis of case study data is the most difficult and

least developed or described aspect of conventional CSR

(Carolan et al., 2016; Cronin, 2014; Yin, 1994). At a

broad level, consistent with conventional CSR, our CSOR

approach to exploring collaboration in practice teams

involved combining multiple sources of evidence to form

case study conclusions (Yin, 2014). However, in contrast

to conventional approaches, where independently col-

lected sources of data either generate separate findings or

integrate simultaneously in the analysis phase to form

overall case findings (Yin, 2014), CSOR involves an

explicitly sequential approach to analysis (see Figure 1).

A recurring part of the problem with previously pub-

lished research involving multiple methods is that the

interview data governs the framework for the analysis

(Morgan et al., 2015). In contrast, in the SIPP Study, as

recommended by Morse (2010), each of the different

sources of data was initially analyzed and reported sepa-

rately prior to the result-integration phase. However, the

initial analysis stemmed from the observation data as a

stand-alone data set, which then informed interview ques-

tion areas probed during subsequent interviews with indi-

vidual practice team members. The CIHC (2010)

competency framework (including interprofessional

communication, patient-centered care, team functioning,

role clarification, and conflict resolution) was the starting

point that informed the preliminary iterative analysis.

Using an overall inductive process (Lincoln & Guba,

1985), the CIHC framework along with de novo catego-

ries emerging from the observation data (most relating to

contextual influences on IPC) was used to establish the

analytic framework contained within each of the descrip-

tive case reports. Interview transcripts were then exam-

ined to confirm, supplement, and expand on the

observation data in each report.

The descriptive case reports provided a clear chain of

evidence linking the detailed case study findings back to

the different forms of raw data (Yin, 2014). They also iden-

tified similarities as well as potentially important differ-

ences between data sources. In a second level of analysis, a

general thematic analysis of descriptive case reports (Braun

& Clarke, 2006) was undertaken, integrating the observa-

tion and non-observation data to generate the case-specific

themes. Similarities and differences among the case-spe-

cific themes were examined, and overarching cross-case

themes were produced. In the course of this inductive ana-

lytic process, the CIHC framework did not emerge as key

explanatory themes. Using the observation data as the

foundation for the analysis in the SIPP Study revealed new

understandings about key factors influencing effective IPC

that may not have emerged otherwise. Most notably, this

included the importance of contextual/organizational ele-

ments (the built environment, practice location, and busi-

ness models), which fostered opportunities for frequent,

shared informal communication (Pullon et al., 2016).

Observation Data Explicitly Referenced in

Final Results

In the final stage of CSR, adequately reporting the com-

plexity of case findings can be difficult (Baxter & Jack,

2008; Yin, 2014), particularly within the space constraints

of health care journals. As with any qualitative study,

publications ought to reference specific data examples.

This provides readers with the opportunity to examine the

detail and evaluate the chain of evidence to determine

how conclusions have been reached (Rowley, 2002; Yin,

2014). Yet, in most previous research examining IPC in

primary care, referenced examples from observation data

are rare, either not mentioned beyond the methods

description or referred to ambiguously, embedded within

descriptions of the study findings (Morgan et al., 2015).

In contrast, in the reported results of the SIPP Study,

examples have been included from each of the different

data sources and clearly referenced back to the original

field notes or other sources (Pullon et al., 2016). Ensuring

reported findings are explicitly referenced to data sources

in published articles improves the rigor of the research by

not only making the chain of evidence transparent but

also further increasing the likelihood that the reported

findings are not disproportionally represented by self-

reported interview data.

Morgan et al. 1065

Discussion

This article has proposed a new framework, CSOR, for

conducting observationally driven CSR in health care set-

tings. Because of the potential for observation data to

contribute uniquely to research findings, CSOR positions

observation data at the center of the research design:

Observation data are collected prior to and inform the

subsequent collection of non-observation data, and deter-

mine the analytic framework and are explicitly referenced

in the final results. The fundamental assumption of the

approach is that observation is an optimal method for

investigating health care phenomena, which are known to

be difficult to measure, such as IPC, and where the focus

Figure 1. Case study observational research: Sequence of data collection and analysis.

1066 Qualitative Health Research 27(7)

of the research involves examining how people go about

an activity of research interest in a particular naturally

occurring context. The knowledge that observation pro-

vides significant advantages over self-reported forms of

data is not new. However, there is a lack of guiding

frameworks available to inform researchers wishing to

use observation methods in multiple-method studies, in a

way that gives precedence to the observation data.

The key advantage of utilizing a CSOR approach is that

through combining observation with other forms of data

collection in a CSR design that prioritizes the observation

data, a richer understanding of the phenomena of interest

can be achieved. Previous research undertaken in health

care settings has underutilized observation data, resulting in

a predominance of interview-based findings, which appear

to underrepresent wider contextual influences (Morgan

et al., 2015). In our study, using the CSOR framework

revealed important contextual elements influencing effec-

tive IPC in primary care teams that had not previously been

identified from interview-dominated studies.

Collecting and analyzing observation data prior to col-

lecting interview data is a clear strength of the CSOR

approach. This sequential design enabled the research nurse

to focus on enabling the context to “speak for itself.” It also

provided the opportunity to undertake observation-informed

context-specific interviews, revealing important information

that may otherwise have been missed. Yet, this sequential

design is not without limitations. An important potential risk

of using observational findings to inform interviews is that

the interviews may raise ethical issues for participants.

However, this did not appear to be the case in our study

where the selection of observation material discussed during

interviews was enriched by the appreciative inquiry

approach. In addition, as reported by others using similar

qualitative methods in natural settings (Wiles, Coffey,

Robison, & Prosser, 2013), ethical safety in our study was

further improved by developing relationships of mutual trust

with the research participants.

The strength of the sequential design was augmented

by the non-participant observer role adopted, allowing the

research nurse to unobtrusively observe practice teams

from a quasi-“neutral” perspective without any insider

knowledge of how each of the particular teams functioned.

Participant observation, where the researcher is also an

active member of the team, has the advantage of increas-

ing the likelihood participants will behave naturally as the

presence of an outsider can influence behavior. However,

through the feedback from the practice teams involved

and subsequent interviews, we did not find any evidence

of participant discomfort with the observations under-

taken in our study. Our research nurse’s independent role,

along with the appreciative inquiry approach used, is

likely to have facilitated her being readily accepted into

the practices by the research participants. Importantly,

with either type of observer role used, the resulting field

notes must be interpreted as reported accounts of what the

observer chooses to observe and record (Caldwell &

Atwal, 2005), and reflect a mutual influence between the

observer and the observed (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

CSOR provides an alternative to more complex observa-

tional approaches such as traditional ethnography. Whereas

traditional ethnographers typically enter the field for sus-

tained periods of time without any formally specified

research questions (Cohen & Court, 2003; Roper & Shapira,

2000), CSOR aims to better understand specific complex

naturally occurring phenomena through the examination of

selected cases. However, the unstructured observation com-

ponent of the CSOR approach was still a time-intensive

aspect in our study. Other limitations of the CSOR frame-

work in its current form are recognized in that it is an explor-

atory approach, developed iteratively in the course of a study

investigating IPC in primary care. More research is needed

to further explore and verify the approach. Nonetheless,

CSOR will be of interest to researchers working in a wide

range of health care settings. CSOR is a modified approach

to one form of multiple-method research, CSR. Future

research could explore how to extend the principles of the

approach to other multiple-method research designs.

Conclusion

Health care research incorporating multiple methods would

benefit from more effectively utilizing observation data

because of the potential for direct observation techniques to

contribute unique knowledge and understanding. The CSOR

framework presented in this article is an adapted form of

CSR and is in early stages of development. The CSOR

framework has been referenced by a study investigating IPC

in primary care teams and provides a distinctive approach to

CSR that explicitly prioritizes the observation data through-

out all stages of the research. The approach was well received

by study participants and proved its value, revealing impor-

tant contextual factors influencing effective IPC that had not

previously been identified from interview-based studies.

Case study observational research developed out of a

study undertaken in a primary care context; however, the

principles of this approach are applicable to researchers

working in a wide range of health care settings. In particu-

lar, CSOR appears a promising framework for exploring

complex research topics where contextual issues are of

primary concern.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect

to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support

for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:

This study was funded by grants from the University of Otago

Morgan et al. 1067

Research Committee and the New Zealand Lottery Health

Research Council (Grant 313641).

References

Abma, T. A., & Stake, R. E. (2014). Science of the par-

ticular: An advocacy of naturalistic case study in health

research. Qualitative Health Research, 24, 1150–1161.

doi:10.1177/1049732314543196

Anthony, S., & Jack, S. (2009). Qualitative case study method-

ology in nursing research: An integrative review. Journal

of Advanced Nursing, 65, 1171–1181. doi:10.1111/j.1365-

2648.2009.04998.x

Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodol-

ogy: Study design and implementation for novice research-

ers. The Qualitative Report, 13, 544–559. Retrieved from

http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/

Bazeley, P., & Jackson, K. (2013). Qualitative data analysis

with NVivo. London: Sage.

Bloomer, M. J., Cross, W., Endacott, R., O’Connor, M., &

Moss, C. (2012). Qualitative observation in a clinical set-

ting: Challenges at end of life. Nursing & Health Sciences,

14, 25–31. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00653.x

Bloomer, M. J., Doman, M., & Endacott, R. (2013). How

the observed create ethical dilemmas for the observers:

Experiences from studies conducted in clinical settings

in the UK and Australia. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15,

410–414. doi:10.1111/nhs.12052

Boblin, S. L., Ireland, S., Kirkpatrick, H., & Robertson, K.

(2013). Using Stake’s qualitative case study approach

to explore implementation of evidence-based prac-

tice. Qualitative Health Research, 23, 1267–1275.

doi:10.1177/1049732313502128

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psy-

chology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Caldwell, K., & Atwal, A. (2005). Non-participant observation:

Using video tapes to collect data in nursing research. Nurse

Researcher, 13, 42–54. Retrieved from http://journals.rcni.

com/journal/nr

Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. (2010).

A national interprofessional competency frame-

work. Retrieved from http://www.cihc.ca/files/CIHC_

IPCompetencies_Feb1210.pdf

Carolan, C. M., Forbat, L., & Smith, A. (2016). Developing

the DESCARTE Model: The design of case study research

in health care. Qualitative Health Research, 26, 626–639.

doi:10.1177/1049732315602488

Carroll, K., Iedema, R., & Kerridge, R. (2008). Reshaping

ICU ward round practices using video-reflexive eth-

nography. Qualitative Health Research, 18, 380–390.

doi:10.1177/1049732307313430

Cohen, A., & Court, D. (2003). Ethnography and case study:

A comparative analysis. Academic Exchange Quarterly, 7,

283–287.

Collier, A., Phillips, J. L., & Iedema, R. (2015). The mean-

ing of home at the end of life: A video-reflexive eth-

nography study. Palliative Medicine, 29, 695–702.

doi:10.1177/0269216315575677

Cooperrider, D., & Srivastva, S. (1987). Appreciative inquiry in

organizational life. In R. Woodman & W. Pasmore (Eds.),

Research in organizational change and development (pp.

129–169). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Cronin, C. (2014). Using case study research as a rigorous form

of inquiry. Nurse Researcher, 21(5), 19–27. doi:10.7748/

nr.21.5.19.e1240

Curry, L. A., Nembhard, I. M., & Bradley, E. H. (2009).

Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contribu-

tions to outcomes research. Circulation, 119, 1442–1452.

doi:10.1161/circulationaha.107.742775

Dowell, T., Macdonald, L., Stubbe, M., Plumridge, E., & Dew,

K. (2007). Clinicians at work: What can we learn from

interactions in the consultation? New Zealand Family

Physician, 34, 345–350.

Forsyth, R., Carroll, K., & Reitano, P. (2009). Introduction.

International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 3,

214–217. doi:10.1080/18340806.2009.11004911

Furlong, M. (2010). Clear at a distance, jumbled up close:

Observation, immersion and reflection in the process that

is creative research. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Research

methods in health: Foundations for evidence-based prac-

tice (pp. 153–169). South Melbourne, Australia: Victoria

Oxford University Press.

Hjalmarson, H. V., Ahgren, B., & Kjölsrud, M. S. (2013).

Developing interprofessional collaboration: A longitudinal

case of secondary prevention for patients with osteoporo-

sis. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27, 161–170. doi:10.

3109/13561820.2012.724123

Houghton, C., Casey, D., Shaw, D., & Murphy, K. (2013). Rigour

in qualitative case-study research. Nurse Researcher, 20(4),

12–17. doi:10.7748/nr2013.03.20.4.12.e326

Iedema, R., Merrick, E. T., Rajbhandari, D., Gardo, A., Stirling,

A., & Herkes, R. (2009). Viewing the taken-for-granted

from under a different aspect: A video-based method

in pursuit of patient safety. International Journal of

Multiple Research Approaches, 3, 290–301. doi:10.5172/

mra.3.3.290

Kislov, R., Walshe, K., & Harvey, G. (2012). Managing bound-

aries in primary care service improvement: A developmen-

tal approach to communities of practice. Implementation

Science, 7, Article 97. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-7-97

Landsberger, H. A. (1958). Hawthorne revisited: Management

and the worker, its critics, and the developments in human

relations in industry. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly

Hills, CA: Sage.

Lingard, L., Espin, S., Whyte, S., Regehr, G., Baker, G. R.,

Reznick, R., . . . Grober, E. (2004). Communication fail-

ures in the operating room: An observational classification

of recurrent types and effects. Quality and Safety in Health

Care, 13, 330–334. doi:10.1136/qshc.2003.008425

Lingard, L., Reznick, R., Espin, S., Regehr, G., & De Vito, I.

(2002). Team communications in the operating room: Talk

patterns, sites of tension, and implications for novices.

Academic Medicine, 77, 232–237. doi:10.1097/00001888-

200203000-00013

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (1995). Observational methods in

health care settings. British Medical Journal, 311(6998),

182–184. doi:10.2307/29728110

Morgan, S. (2013). Miscommunication between patients and

general practitioners: Implications for general practice.

1068 Qualitative Health Research 27(7)

Journal of Primary Health Care, 5, 123–128. Retrieved

from https://rnzcgp.org.nz/assets/documents/Publications/

JPHC/June-2013/JPHCOSPMorganJune2013.pdf

Morgan, S., Pullon, S., & McKinlay, E. (2015). Observation

of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care

teams: An integrative literature review. International

Journal of Nursing Studies, 52, 1217–1230. doi:10.1016/j.

ijnurstu.2015.03.008

Morse, J. M. (2003). Perspectives of the observer and the

observed. Qualitative Health Research, 13, 155–157.

doi:10.1177/1049732302239595

Morse, J. M. (2010). Simultaneous and sequential qualitative

mixed method designs. Qualitative Inquiry, 16, 483–491.

doi:10.1177/1077800410364741

Morse, J. M., & Cheek, J. (2014). Making room for qualita-

tively-driven mixed-method research. Qualitative Health

Research, 24, 3–5. doi:10.1177/1049732313513656

Mulhall, A. (2003). In the field: Notes on observation in qualita-

tive research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 41, 306–313.

doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02514.x

Murphy, E., & Dingwall, R. (2007). Informed consent, antic-

ipatory regulation and ethnographic practice. Social

Science & Medicine, 65, 2223–2234. doi:10.1016/j.socs-

cimed.2007.08.008

Oandasan, I. F., Conn, L. G., Lingard, L., Karim, A., Jakubovicz,

D., Whitehead, C., . . . Reeves, S. (2009). The impact of

space and time on interprofessional teamwork in Canadian

primary health care settings: Implications for health care

reform. Primary Health Care Research & Development,

10, 151–162. doi:10.1017/S1463423609001091

O’Cathain, A., Murphy, E., & Nicholl, J. (2008). The qual-

ity of mixed methods studies in health services research.

Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 13, 92–98.

doi:10.1258/jhsrp.2007.007074

Ødegard, A. (2006). Exploring perceptions of interprofessional

collaboration in child mental health care. International

Journal of Integrated Care, 6, e25. Retrieved from http://

www.ijic.org/index.php/ijic

Phillips, C. B., Dwan, K., Hepworth, J., Pearce, C., & Hall, S.

(2014). Using qualitative mixed methods to study small

health care organizations while maximising trustworthi-

ness and authenticity. BMC Health Services Research, 14,

Article 559. doi:10.1186/s12913-014-0559-4

Proudfoot, J., Jayasinghe, U. W., Holton, C., Grimm, J., Bubner,

T., Amoroso, C., . . . Harris, M. F. (2007). Team climate

for innovation: What difference does it make in general

practice? International Journal for Quality in Health Care,

19, 164–169. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm005

Pullon, S., Morgan, S., Macdonald, L., McKinlay, E., & Gray,

B. (2016). Observation of interprofessional collaboration

in primary care practice: A multiple case study. Manuscript

submitted for publication.

Quinlan, E. (2008). Conspicuous invisibility: Shadowing

as a data collection strategy. Qualitative Inquiry, 14,

1480–1499. doi:10.1177/1077800408318318

Roper, J., & Shapira, J. (2000). Ethnography in nursing

research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rowley, J. (2002). Using case studies in research. Management

Research News, 25, 16–27. doi:10.1108/01409170210782990

Russell, G., Advocat, J., Geneau, R., Farrell, B., Thille, P.,

Ward, N., & Evans, S. (2012). Examining organizational

change in primary care practices: Experiences from using

ethnographic methods. Family Practice, 29, 455–461.

doi:10.1093/fampra/cmr117

Savage, J. (2000). Ethnography and health care. British Medical

Journal, 321, 1400–1402. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7273.1400

Sinclair, L. B., Lingard, L. A., & Mohabeer, R. N. (2009). What’s

so great about rehabilitation teams? An ethnographic study

of interprofessional collaboration in a rehabilitation unit.

Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90,

1196–1201. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2009.01.021

Strasser, D. C., Falconer, J. A., Stevens, A. B., Uomoto, J.

M., Herrin, J., Bowen, S. E., & Burridge, A. B. (2008).

Team training and stroke rehabilitation outcomes: A clus-

ter randomized trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and

Rehabilitation, 89, 10–15. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.127

Walshe, C., Ewing, G., & Griffiths, J. (2012). Using obser-

vation as a data collection method to help under-

stand patient and professional roles and actions in

palliative care settings. Palliative Medicine, 26,

1048–1054. doi:10.1177/0269216311432897

Wiles, R., Coffey, A., Robison, J., & Prosser, J. (2013). Ethical

regulation and visual methods: Making visual research

impossible or developing good practice? Sociological

Research Online, 17, 8. doi:10.5153/sro.2274

Xyrichis, A., & Lowton, K. (2008). What fosters or prevents

interprofessional teamworking in primary and community

care? A literature review. International Journal of Nursing

Studies, 45, 140–153. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.01.015

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods

(2nd ed.). Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage.

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods

(5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Author Biographies

Sonya J. Morgan (MHealSc) is a research fellow in the

Department of Primary Health Care and General Practice at the

University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand.

Susan R. H. Pullon (MPHC FRNZCGP MBChB) is an associ-

ate professor and the head of the Department of Primary Health

Care and General Practice at the University of Otago,

Wellington, New Zealand.

Lindsay M. Macdonald (MA [App], RN) is a research fellow

in the Department of Primary Health Care and General Practice

at the University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand.

Eileen M. McKinlay (MA [App], Ad Dip Nurs, RN) is a senior

lecturer in the Department of Primary Health Care and General

Practice at the University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand.

Ben V. Gray (MBHL, MBChB) is a senior lecturer in the

Department of Primary Health Care and General Practice at the

University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand.